By Edson Krenak Naknanuk

Brazil is home to 63 percent of the Amazon rainforest peoples and is the country most affected by the new coronavirus in Latin America. Many Indigenous Peoples in Brazil live in remote communities. They are at a higher risk of serious infection from COVID-19 because most of them live in distant areas with limited transport, lack of access to healthcare, food supply, and with obstacles to communication such as poor internet and unreliable electricity. The healthcare structure also is a struggle and intensifies the pandemic threat for Indigenous communities.

Some Indigenous people live close enough to cities and are visited by outsiders. Living in proximity or not, they all have to travel to small towns for education, healthcare, food, and other necessities. The number of those infected with COVID-19 is increasing. This article focuses on Amazonia and highlights some good work done by Indigenous healthcare officers, leaders, and supporters.

Amazonia: An alarming situation

The situation is alarming. Forty-five percent of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil live in the north of the country, where the most populated state, Amazonas, and its capital, Manaus, the largest Northern city, is home to 15,000-20,000 Indigenous people and more than 53 Indigenous languages are spoken. Manaus is now one of the most affected by the novel Coronavirus COVID-19. The health system has collapsed with an increase of 36 percent of cases per day and the deaths of more than one hundred daily as of April 20. The first deaths of Indigenous people from the virus also occurred in Amazonas. A 15-year-old Yanomami boy, and a writer and health agent Aldevan Baniwa, 45, of the Baniwa Peoples. The ones who study (it is the beginning of the school year in Brazil) and work in the cities, like Aldevan Baniwa, are oriented not to go back to their villages, creating a new situation in need for assistance and support.

The SESAI, the State health agency for Indigenous Peoples, employs many Indigenous nurses and a few Indigenous doctors to assist and offer more than healthcare, but also food, and news from the city and hygiene products when available. Some Indigenous health agents gave first-hand accounts of the situation of Indigenous Peoples who have been successful in protecting their communities. Zuleica Tiago Terena is an Indigenous nurse who coordinates the work for the SESAI in 15 villages in Mato Grosso do Sul. When asked how they are fighting the coronavirus, she stated:

“In our villages, we are protecting our people by erecting physical barriers and sanitation barriers to prevent strangers, tourists, missionaries, anthropologies, and other people from visiting us. We have regular educational talks and activities with the community. The local leaders responsible for those actions have the support from SESAI staff. The families or workers that had to go out and came back from travel, are isolated in quarantine. There is a healthcare technician who usually lives in the village and is responsible for monitoring those families. I’m responsible for 15 villages, and not all of them have a local healthcare technician. It would be great if we had at least one per village. The larger villages really need healthcare workers. We do our best here. We are proud of our work for our people. What I see in the State of Amazonas is chaos, a collapse at all levels, in the city, State, Federal, and Indigenous healthcare systems. There is a complex problem because the Indigenous villages in Amazonia are near to each other, and the Indigenous workers work with different tribes in the city then go back home. I don’t think that the isolation policy is clear or has been taken seriously in Amazonas. Now, they are hardest hit by the Coronavirus in the north and northeast of Brazil. We need leaders, and stronger leadership among, and for Indigenous Peoples.”

In the north of the country, in Roraima, Indigenous physician, Onaldo Sena from Kaxinawa Peoples, works for DSEI - Special Indigenous Health Agency, which is a decentralized management unit of the Indigenous Health Care Subsystem (SasiSUS). DSEI is a model service oriented towards a well-defined dynamic, geographic, population, and administrative ethnocultural space, however in the entire country they count only with 34 offices to attend almost 980,000 Indigenous from 416 ethnicities, in more than 6,238 villages.

Sena spoke of the situation of Indigenous people in his area:

“I work in a healthcare unit responsible for more than 50,000 Indigenous people from 7 different ethnic groups. Our patients are from isolated, urban, and suburban areas. The communities that live in the hills are aware of the situation and they are blocking visitors as much as they can, but the problem is they are so afraid that even the healthcare professionals cannot visit them and offer assistance. Scared, some groups are completely closed, in a real lockdown. Indigenous Peoples are part of those at high risk. We are facing an increasing problem of illegal mining and land invaders in our lands in general. The media is reporting all the time about this horrible situation. There is no global and unified message to Indigenous Peoples. But there is a technical note to orient us, health care staff. Because of the lack of personal protection equipment and other basic materials, we cannot do much. Before attending any emergency or request, we have to stay in quarantine, and other problems arise. The State must do more, especially, with information, education, and orientation. A coordinated action between agencies and organizations is necessary. Our communities are blocking visitors and staying safe.”

The Amazonia state is very often discussed, but the other Indigenous regions feel abandoned. Radio Yandê and other Indigenous media gathered Indigenous leaders and listeners to discuss the problem, raising awareness, and orienting. But This is not enough. The media every day informs while the problem increases in the country, it is also escalating among Indigenous Peoples. The Jornal do Brasil, a national newspaper reported on April 24, that leaders of Indigenous Peoples in the Amazon asked for international humanitarian aid in the face of abandonment and the risk they face in the midst of the new coronavirus pandemic.

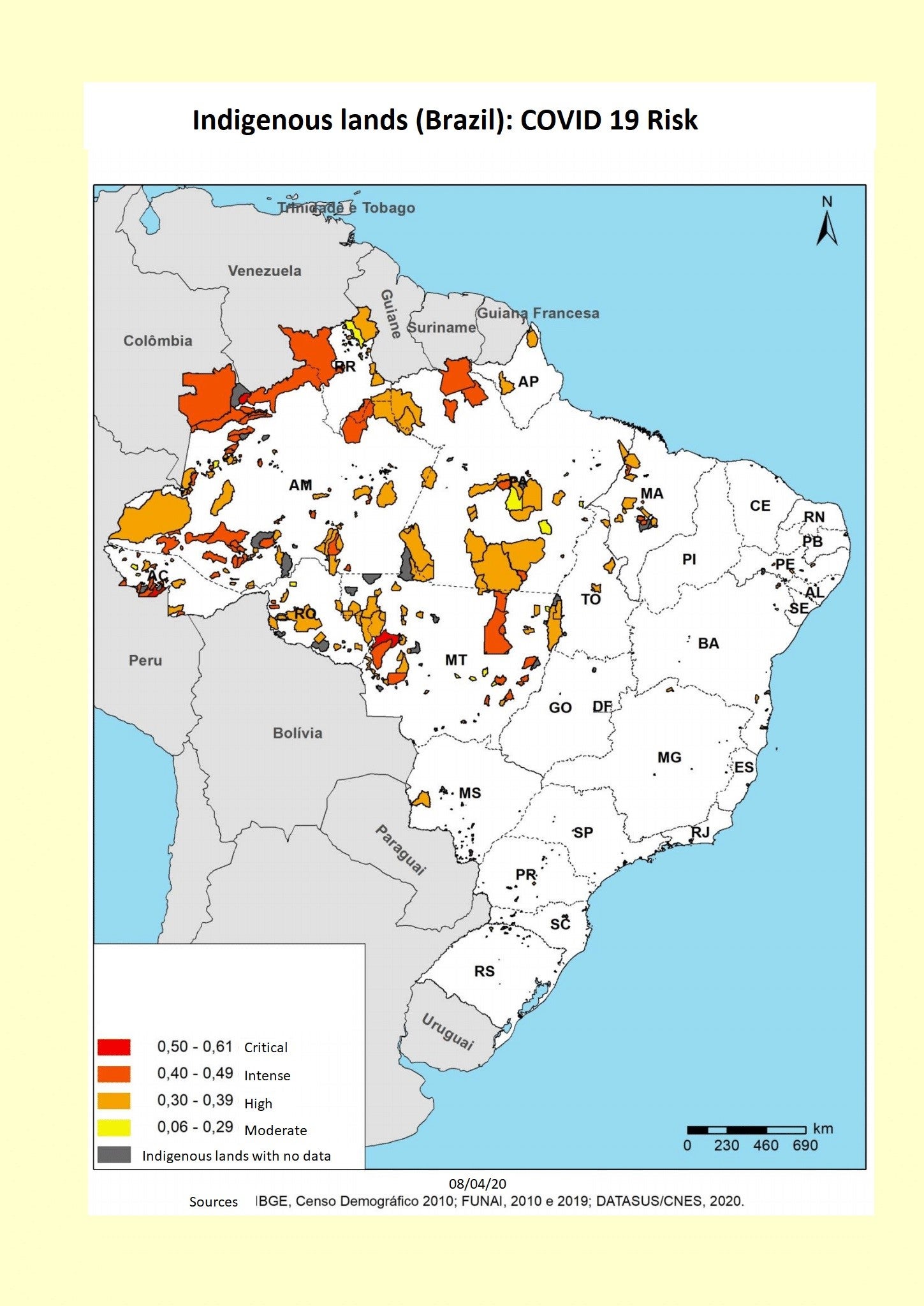

"There are no doctors in our communities, there are no protective materials for this pandemic (...) There is no support in the food issue," said José Gregorio Díaz from the coordination of Indigenous Organizations in the Amazon Basin (COICA) in the Jornal do Brasil. COICA brings together the nine countries that share the largest tropical forest in the world. Other sources are reporting that COVID-19 cases among Indigenous people have grown more than 700 percent in the last five days. On April 25, the ISA monitoring system reported 85 confirmed cases and 7 deaths. A study, “Demographic and Infrastructure Vulnerability Analysis of Covid-19 Indigenous Lands” published on April 24, by researchers from four universities - Unicamp, USP, UFF e UFRJ, affirms that out of the 34 DSEIs there are six that have the highest degree of vulnerability, all in the Amazon region. High-risk Indigenous populations include:Alto Rio Negro (AM) - 19,099 people; Yanomami (RR) - 25,972; Xavante (MT) - 19,213; Xingu (MT) - 6,704; Kaiapó do Pará (PA) - 4,559; Tapajós River (PA) - 6,074. The study also released a map to track and visualize those problems.

The researchers also point out the importance of the participation of Indigenous organizations in the planning and implementing preventive actions against the COVID-19. “They are the main actors, not just subjects of prevention programs. It is people who do all kinds of prevention that they consider appropriate after obtaining all the information about COVID-19. So, any action to improve and mitigate the vulnerability of Indigenous lands to the disease has to be done and acted out together with Indigenous organizations,” the study concludes.

Increasing the danger: invisibility and deprivation

Because of structural problems and lack of resources the SESAI decided to not offer medical care to Indigenous people with COVID-19 symptoms in urban areas, only if they are in the Indigenous territory putting communities at risk. More than 300,000 Indigenous peoples live, work or study in the cities. Infected Indigenous individuals in the cities are not counted in the numbers of epidemiological monitoring organisms. This fact increases substantially the invisibility of Indigenous Peoples during this pandemic time.

Indigenous Peoples are the crucial keepers of biodiversity, a role recognized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a UN group of experts on climate change. Amazonia is an area that contains an estimated 200 billion tons of carbon. Indigenous ways of natural resource management are successful. The rate of deforestation on Indigenous lands is less than half that recorded in other areas, but these communities are threatened by illegal activities and large agricultural projects promoted by governments.

Indigenous Peoples have faced threats like this before with devastating consequences for many relatives. The impacts of COVID-19 are unprecedented and terrifying because due lands and resources depletion, Indigenous people cannot now flee and escape into their territories. Some depend on the State, and many communities live in poverty and near the cities.

To lessen the emotional suffering, I end this article with a poem. Imagination has a clear path to save us in these times, moving us towards actions.

There is a valley of bones, old white bones, sighing bits of life...

And the birds dare to work out there... yearning over the valley

chasing a dirty urubu who scares the humans

everybody looks when a cricked rustled

through the bones reminding them that

Life

is breaking through laughing

--Edson Krenak Naknanuk is an Indigenous activist and writer in Brazil and a Cultural Survival consultant. Currently, he is a Ph.D. candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology with studies in Legal Anthropology at Vienna University, Austria. He is also a teacher. He loves interacting with children and youth and preparing them for a better world.