By CS Staff

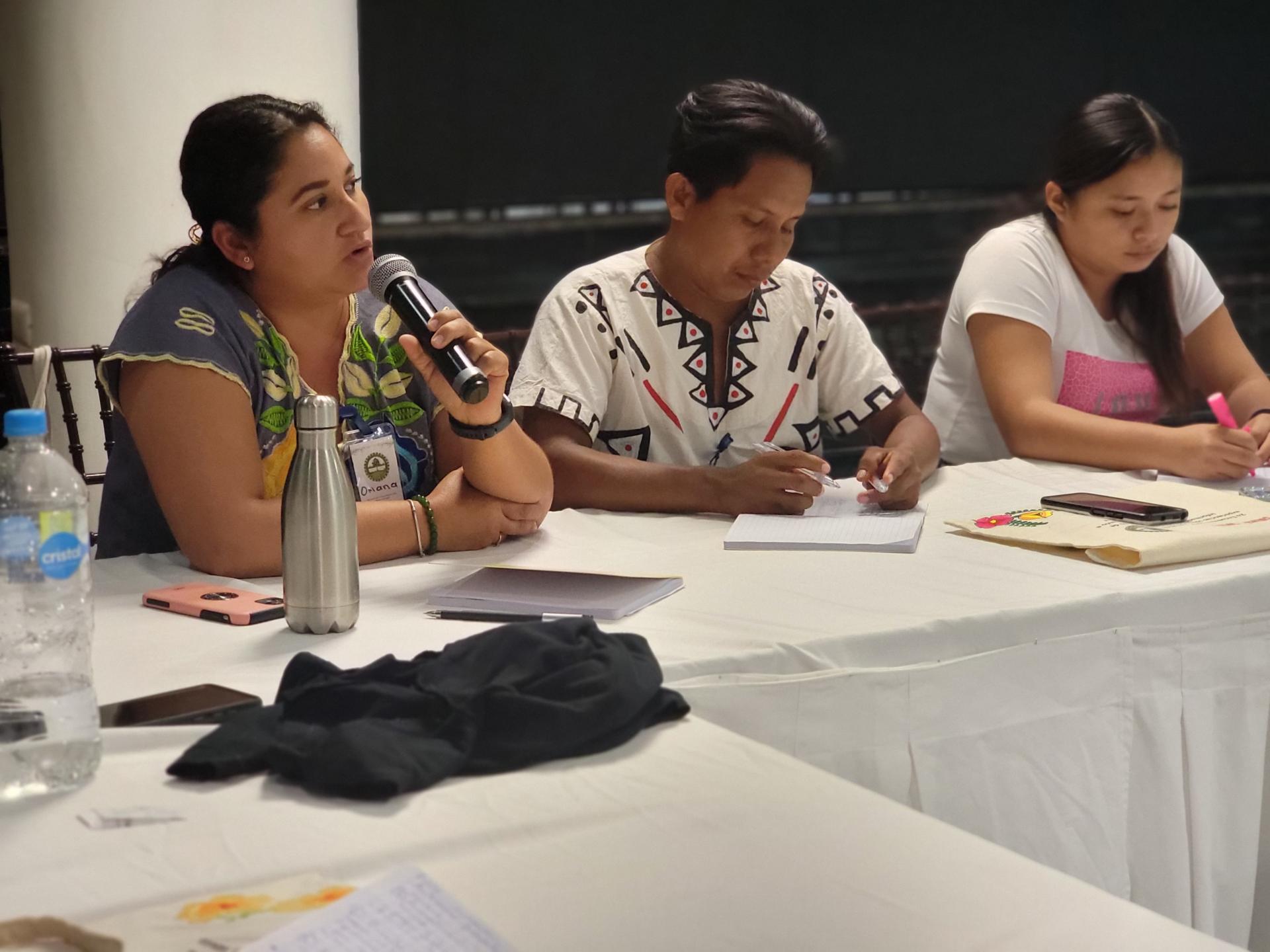

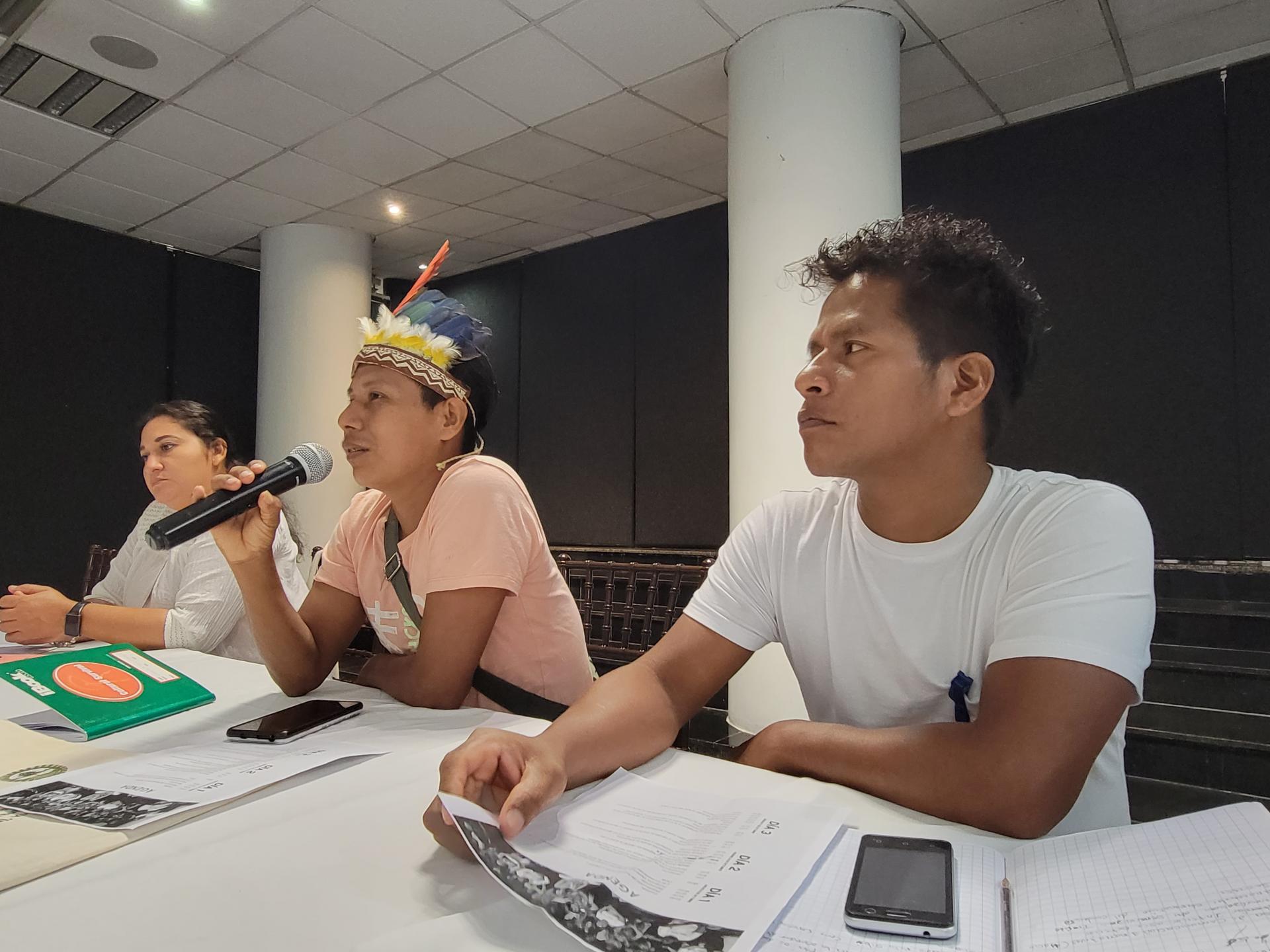

“We realize that all Indigenous Peoples have the same issues, the same sufferings. What does that mean? That in all our countries our collective rights and individual rights as people and as Peoples are being violated,” Arthur Francis Cruz Ochoa (Huitoto Murui), Indigenous land defender from the northeast Amazon region, said at the Second Meeting and Exchange on Free, Prior and Informed Consent held in Jo'/Mérida, Yucatán, October 5-8, 2023. As a member of the Federation of Native Communities of the Nanay River, Cruz Ochoa and his Centro Arenal community of around 200 people resist illegal logging of their forests, trafficking, land dispossession, pollution, and extractive projects that gravely violate the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Cultural Survival organized the event as a space for attendees to reflect on their experiences and visions about their fundamental right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent. Some 40 Indigenous land defenders hailing from the Yucatán Peninsula and other regions of Mexico, as well as Costa Rica and Peru, representing the Ayuujk, Binnizá, Bribri, Chontal, Maijuna, Maya, Murvi Buee, Nahua, Ñuu Savi, Otomí, Purépecha, Tzotzil, and Tseltal Peoples, participated in the exchange.

Free, Prior and Informed Consent is enshrined in articles of several binding international agreements. Two such instruments, International Labour Organization Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, recognize the right of Indigenous Peoples to determine and collectively develop their priorities and strategies for development and for the use of their lands or territories and other resources. By virtue of this right, Indigenous Peoples can also freely determine their political status and their cultural, social, and economic development; in other words, Indigenous Peoples are guaranteed the right to self-determination. As a consequence, States are obliged to uphold Indigenous autonomy. Before commencing any project or legislative or administrative measures that may directly affect Indigenous Peoples or their lands, territories, and resources, they must first hold consultations and cooperate in good faith with Indigenous Peoples through their own representative institutions and in a way that conforms with Indigenous languages and cultures. This is particularly salient in relation to the development, use, or exploitation of minerals, water, oil, energy, and other natural resources. Of course, this also includes the right of Indigenous Peoples to withhold consent or accept the proposed projects with modifications or terms defined by the communities.

Cruz Ochoa explained that the rights that constitute FPIC are used as a “tool for territorial defense” among the Huitoto communities of the Amazon. “With prior consultation, we have stopped many projects. Sometimes we have to use this tool but think carefully about how we do it. Furthermore, the fact that we ask for prior consultation does not mean that we are accepting,” he said. Although legal tools such as consultation have been fundamental for the defense of Indigenous territory, language, and culture, in general, States are not respectful of the rights of Peoples—quite the opposite, several participants affirmed.

“The State considers us minors. [They say] that we are subjects of consultation, subjects of dialogue, [but] these are rights that are not recognized. If we stand on the basis of autonomy and self-determination we will not wait for the State to arrive and consult us. We are not asking for [the projects they’re proposing]; they are not projects done from our perspectives, nor are they based on our needs...In Magú, the highest authority is the community assembly,” said Berenice Sánchez (Otomí) from the Otomí Nacazcahuacán/San Francisco Magú community in Mexico. Since 2011, Sánchez and her community have fought against deforestation and the construction of new hotels, managing to stop megaprojects and be recognized as an Indigenous Peoples—something that the State of Mexico had always refused to do. She also expressed, along with other participants, that Indigenous Peoples have achieved recognition of their rights through organization and collective resistance, never as a concession from the States. They have done so over the centuries, first by resisting European colonizers, and then Nation States.

Today, many Indigenous Peoples and communities engage in resistance and are demanding their autonomy in the context of State-sanctioned violence, organized crime, and corporations. Indigenous communities frequently become divided along political lines, so in many cases, their processes of achieving autonomy have begun by getting rid of political parties. “In Chilón, the community government began because we recognized that the political parties only support the interests of the capitalists. We formed our community government as a way to defend our territory,” said Pascuala Vásquez Aguilar (Tseltal), spokesperson for the Community Government Council of the municipality of Chilón in Chiapas, Mexico.

Attendees from the communities that make up the Supreme Indigenous Council of Michoacán shared that through their struggle, they managed to establish and strengthen their self-governance. Through a series of consultations held with and among the communities, they achieved economic and administrative autonomy and were able to directly implement the state budget, according to Pavel Ulianov Guzmán (Purépecha), spokesperson for the Council. Despite this successful experience, Guzmán clarified that “there are different types of autonomies; we cannot only talk about one autonomy. In the case of the Indigenous communities of Michoacán, autonomy has been achieved through legal procedures. There are also de facto autonomies [that exist] without anyone's permission.”

Lawyer and historian Francisco López Bárcenas, (Ñúu Savi/Mixteco), an expert in the history of agrarian struggles and Indigenous rights in Mexico, emphasized that consultations must be held with the entire community, not just with the community’s authorities. Furthermore, they must be done according to the affected communities’ appropriate procedures and through their representative institutions. The most important issue for the autonomy of Indigenous Peoples and communities, López Bárcenas stressed, is being able to “exercise it de facto. Later, we can find ways to back them legally,” he said.

In addition to the violence and abuses of State institutions, it is common to observe in Latin America (especially in the case of Mexico), that even when States seek to comply with the procedure to obtain the consent of Indigenous Peoples and communities, they reduce it to the implementation of consultations that do not conform to the initiative or interest of the Peoples, but rather become a tool to materialize extractive projects in Indigenous territories. “They subject us to obey laws that we do not make, so if we continue to hope for autonomy and self-determination, we have to reflect that fact before submitting to those laws. When we are deciding what to do, [we must acknowledge that] the laws are insufficient to win our cases. We said yesterday that the consultation is a trap. They are processes that wear down the movement [and] the people," said Pedro Uc (Maya), a member of the Assembly of Defenders of the Múuch' Xíinbal Mayan Territory, which represents communities of the Yucatan Peninsula that have seen their territory affected by megaprojects, which, “in the classic conquering way, come to snatch our lands to develop their business."

The Much Kanan I'inaj Seed Collective, an organization of Maya farmers that has been fighting for over a decade against transgenic soybeans, monocultures, and glyphosate in Quintana Roo, warned that the State is approaching the communities without respect for the guaranteed rights of the affected people. As a result, many Peoples choose to take self-determined measures, such as declaring territories free of mining or megaprojects. Such is the case of the Chontal People of Oaxaca, who did not seek consultation, but rather for the State to respect their free determination, according to Armando de la Cruz Cortés (Tzamé/Chontal), a lawyer representing the Tequio Jurídico organization. The Chontal community is fighting against the Interoceanic Corridor megaproject that is being developed in their ancestral territory. There are also 315 active mining concessions in force in their territory, which have caused numerous social and environmental conflicts. Faced with this situation, several communities of the Chontal People have declared their territories, located between Chiapas and Oaxaca, prohibited from mining. "We do not want consultation. What we want is for the communal acts of territories prohibited for mining to be respected as an exercise of free Indigenous self-determination, of autonomy," de la Cruz said.

A recurring reflection at the exchange was that, whether for consultations or freely determined measures, strong community organization is necessary to build and sustain the decisions of the communities in the face of State or business actions. Consultation is not the end, but a means to achieve respect for Indigenous rights. “We must educate so that young people go out and learn but return; we must educate how to be and make a community,” de la Cruz said, adding that in the face of threats to Indigenous Peoples’ territories, it is important to strengthen the social fabric. We must promote our own economic projects, share information, generate communication within the communities, and strengthen the participation of everyone, as well as train the younger generations, since they will be the defenders of our territories in the future. In addition, we need to create Indigenous organizations, resistance movements, and community assemblies independent of the State and strengthen and promote the participation of women.

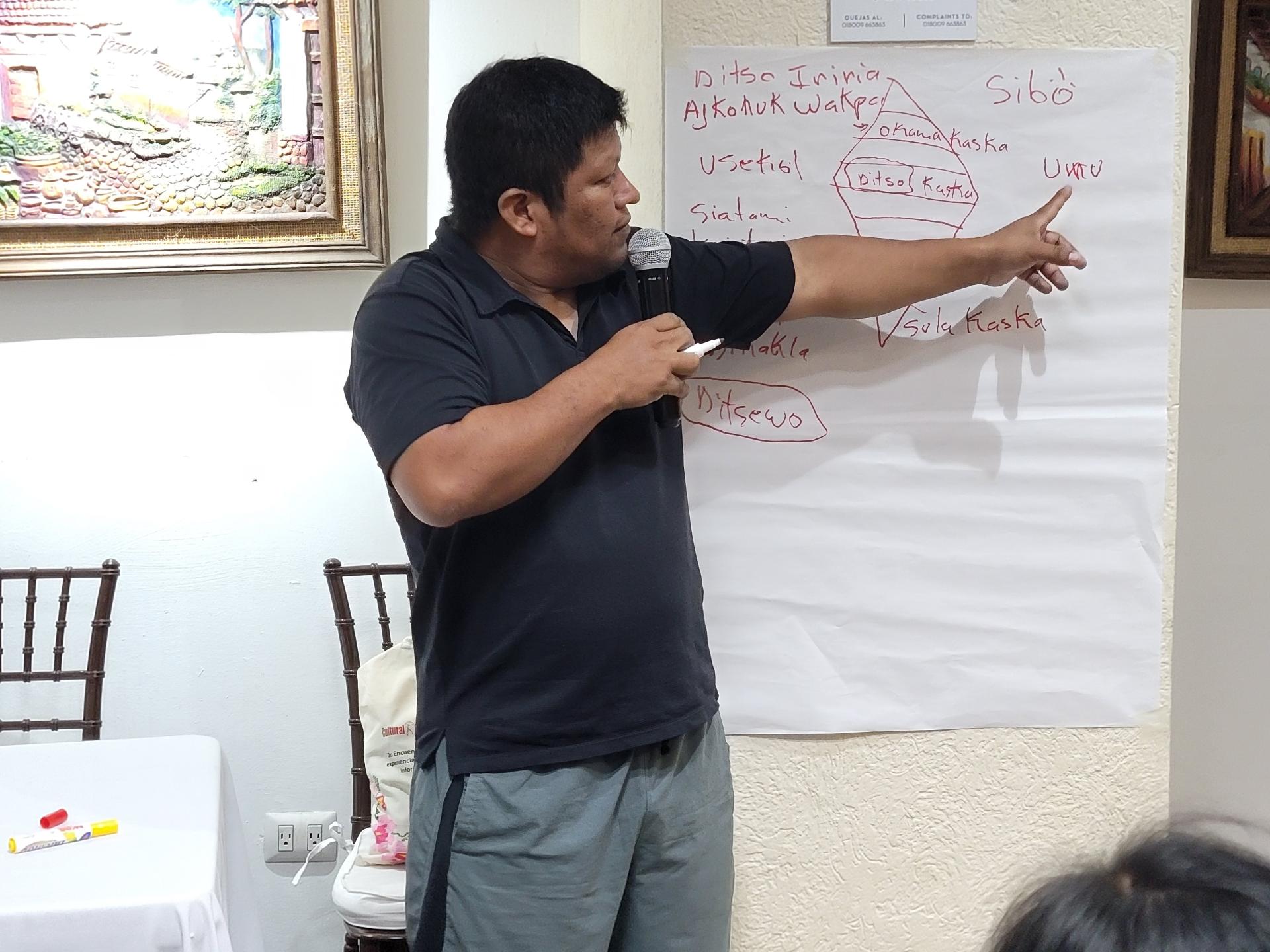

Several participants also expressed that it is important to safeguard the historical memory of our people by strengthening our languages and oral histories and to show that even after colonization, we exist as Peoples and have our own ways of life and organization. Lesner Figueroa (Bribri) from Costa Rica, commented, “As the Bribri Peoples, we do not have any [involvement] with religious issues of any kind. Christianity has nothing to do with us. We have a creator called Sibú, who could be translated as 'god,' but this is also a bad translation. He is the creator of the seeds; that is, of the clans.”

The exchange was an enriching experience for all who participated. It left us with ideas that can be useful for other experiences of defense of the territory and ways of life of Indigenous Peoples. It bears repeating that the self-determination of Indigenous Peoples is the fundamental principle in the defense of our territories, culture, languages, and governments. For this principle to be effectively exercised, it is of utmost importance to strengthen community organization. If consultations are put at the center of struggles or demands without understanding them as a fundamental part of a series of equally or even more important rights, there is a risk that the interests of the State or corporations will overrun not just Indigenous territories, but Indigenous autonomy.

Read: Defending Our Lands Against Dispossession and Capitalist Violence in Southeastern Mexico