Hartman Deetz is an enrolled member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and owner of Ockway Bay Wampum, a small business specializing in contemporary wampum jewelry. Wampum is a bead cut from the Quahog shell and used by Indigenous Peoples in the Northeastern region of North America to create wampum belts. These belts were created as treaties between Tribal Nations and symbolized an ongoing commitment to reciprocity. “The Wampum bead was more than just a bead,” said Deetz. “It was also a promise, a memory, a sacred language of the past and future.”

Recently, Cultural Survival’s Indigenous Rights Radio spoke with Deetz and human rights lawyer and founder of Divest Invest Protect, Michelle Cook (Diné), to discuss their work on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples wampum belt and how wampum has been used throughout the history of the United States. Wampum belts were used in treaty-making, legal agreements, and ceremonial activities. “They demonstrate Indigenous Peoples’ political systems and governing institutions that existed long before the formation of the United States of America and continue to exist today,” Cook said. “These wampum belts are incredibly important because they provide us a window into another way of governing, another way of relating to the world and the universe around us.”

Wampum belts are a form of writing, with symbols woven into the belt serving as a mnemonic device for those who are carrying that knowledge for the community and sharing it through stories, keeping the oral tradition alive. Each wampum belt tells a different story. The Two Row Wampum Belt (Teioháte and Kaswenta --Two Paths/Roads in Mohawk or Tekani teyothata’tye kaswenta and Aterihwihsón:sera Kaswénta in Cayuga), which is among the oldest treaty agreements in North America, illustrates a story between European settlers in one boat and Indigenous Peoples (Haudenosaunee) in another, traveling the river together. It states that neither one will try to steer the other’s boat, that they will share the river and respect each other’s ways of life. The Two Row Wampum signified a shared commitment of friendship, respect, peace and to co-exist. “It was an agreement that recognized the sovereignty of both the settler nation and the Indigenous Peoples, but also recognized their sovereignty in that there wouldn’t be interference, that there shouldn’t be interference in steering the boat,” Cook said.

Cook and Deetz met in 2018 at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York when Deetz brought wampum as gifts to panel speakers, including Cook. “It’s sort of a customary gift from the people of the land, from my people, something that’s also emblematic of coastal people of New England,” said Deetz.

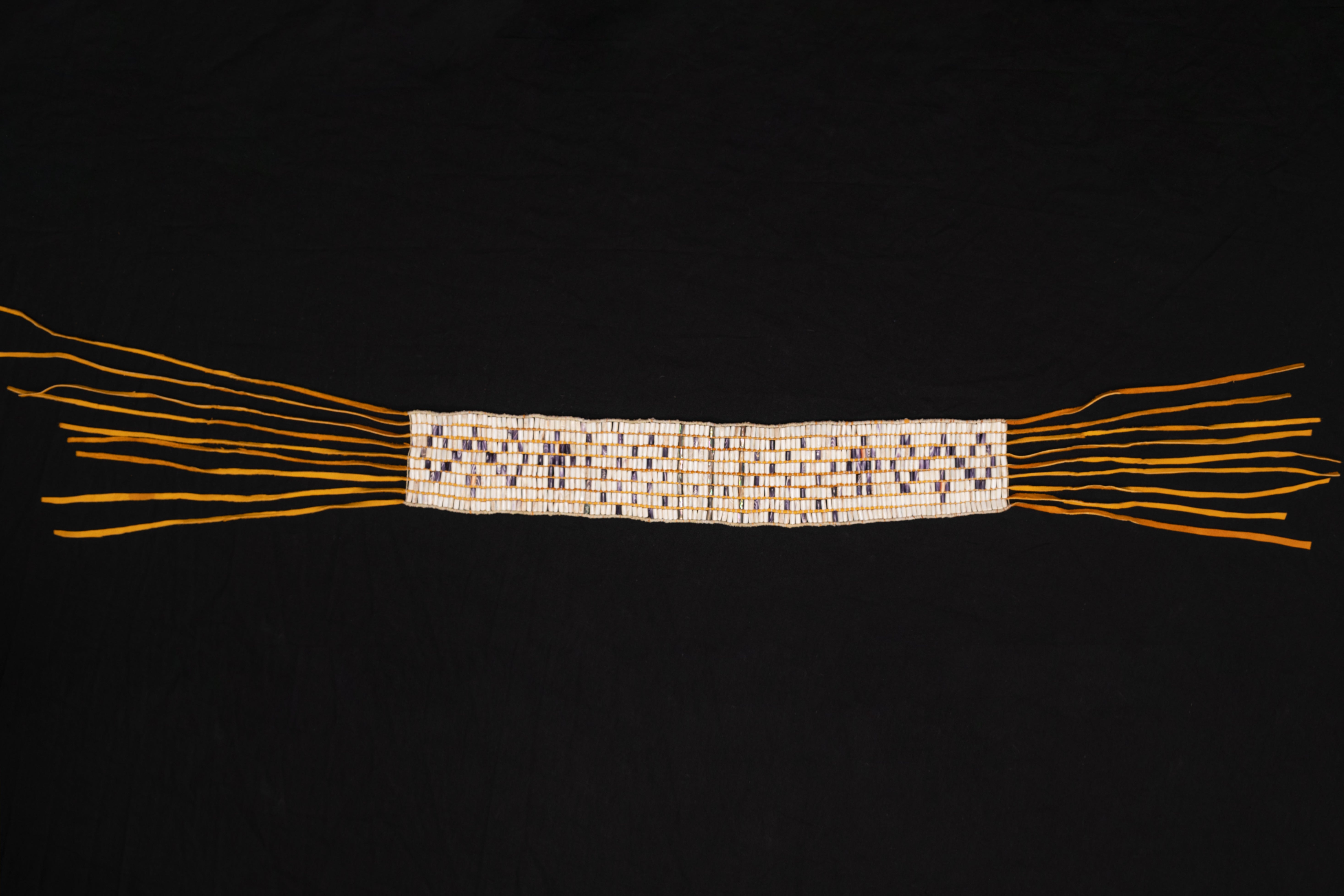

UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Wampum Belt.

Cook was familiar with wampum, and she and Deetz began discussing what wampum meant and how the belts are representative of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. Deetz and Cook soon began to wonder how a modern treaty could be represented in a modern wampum belt, in order to teach about human rights and more importantly to initiate larger conversations about contemporary Indigenous political economic alliances, jurisgensis, confederacy, and potentialities of Indigenous law and governance today and in the future. “Indigenous people should be empowered . . . and respected to be able to enter into those agreements in the modern times as well as something that we did historically, and wampum has largely been spoken of and talked about [in the context of] historic treaties and things of the past,” Deetz said. “We’re constantly talked about in the past tense, and we wanted to think of a modern treaty or legal agreement that could be embodied in a wampum belt.”

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples seemed to be a perfect choice, given that it is an existing legal agreement supported by the international community. “We felt that that helped to underscore the weight of these belts as legal documents and validated the ability of Indigenous governance to have the self-determination to enter into agreements such as [the Declaration] or other agreements . . . that could benefit us,” said Deetz.

One of the main reasons behind creating a Declaration wampum belt, according to Cook, was to help spark global conversations on Indigenous Peoples’ rights: “As an Indigenous human rights lawyer, how do I teach human rights in a decolonized methodology? Part of what we’re doing here is we’re trying to teach the Declaration using an Indigenous Peoples’ methodology and technology so that we can not only teach the Declaration, but so that we can challenge how legal education is perceived and taught in the United States.”

Cook believes that Indigenous Peoples should be taught law through their own epistemological frameworks and that there needs to be a conversation about why the rights of Indigenous Peoples continue to be denied. “We need to continue to put pressure on States and non-State actors, businesses, and corporations to adhere to the principles and standards found within [the Declaration] so that we can fulfill those rights and so that we can prevent the needless deaths of Indigenous Peoples and human rights defenders around the world,” she said.

Showcasing the wampum belts serves as a way to teach others about history and Indigenous traditions, but it also works to challenge global perceptions of Indigenous Peoples. “When we . . . showcase these wampum belts . . . and we teach about these pre-colonial systems of law, we also challenge those racial stereotypes that try to portray our people as less than human, as less than intelligent,” Cook said. “Indigenous Peoples have always had law and governance. We still have a right to make law and live by that law within our lands and jurisdiction today, and anything less than that equity is a vestige and a legacy of the racism that we have inherited through colonization that we have to do away with. If we are going to survive as Indigenous Peoples, but also if we’re going to survive as a human community and family, and if we’re going to fight climate change, we have to start listening to Indigenous Peoples.”

One common theme throughout Cultural Survival’s discussion with Cook and Deetz was that we should look to Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous ways of life to help guide us all as a society. Indigenous Peoples can teach us how to live in harmony with nature and with each other. “What is our law and our way of life going to be if it’s not going to be based on profit, if it’s not going to be based on the infinite extraction of finite resources on Earth? What is going to be the new but ancient way that is going to rebalance us as a society? Indigenous Peoples are the ones who still remember the ancient law of balance, the ancient law of relationships, and that is what this Western capitalist society is missing,” Cook said.

While it is important to take the UN wampum belt to large gatherings or to the UN itself, Cook is more concerned about taking it to grassroots Indigenous communities and empowering them by putting knowledge about the law back into the hands of the people. Cook believes information about human rights and Indigenous law should be accessible to everyone. “We really want the knowledge of human rights to be in the hands of the people who are most denied those human rights,” she said.

The main goal of the UN wampum belt is to start a conversation. “The big thing that we wanted to have come of this,” said Deetz, “is to engage people in conversation and to open up a dialogue about Indigenous Peoples’ rights.” Indigenous communities around the world are fighting every day to protect their lands from extractive industries and to have their inherent rights respected. The UN wampum belt created by Cook and Deetz serves as a way to raise awareness of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and to teach our society how to find balance again.

All photos by Tomas Alejo (Chicano/Huasteca).

Top photo: Michelle Cook and Hartman Deetz with UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Wampum Belt.