Map by Julien KatchinoffAmong remote Indigenous communities in the modern world, Didipio is a success story, both for what the people have made of their land and community and for their courageous struggle to ensure its survival.

Map by Julien KatchinoffAmong remote Indigenous communities in the modern world, Didipio is a success story, both for what the people have made of their land and community and for their courageous struggle to ensure its survival.

Didipio’s original Bugkalot Indigenous residents hunted and gathered in the densely forested mountains; now they collectively manage their forest resources in a sustainable way. Pure and abundant water still tumbles down forested mountains into the Addalam River, nourishing fertile valleys until it empties into the Rio Grande de Cagayan, the Philippines’ longest river.

Photo courtesy of LRC-KsK/FoE PhilippinesThis abundant water makes the Didipio valley perfect for terraced rice farming. Beginning in the 1960s, Indigenous rice farmers moved into the valley from neighboring provinces and built terraces. Some moved at the urging and with assistance from the governmental agency for Indigenous Peoples. Others were forced from their homes in the Agno valley by the construction of hydroelectric dams. Although they came to Didipio by force and through hardship, the Ifugao, Kalanguya, and Ibaloi peoples have made the most of Didipio’s clean and abundant water by producing fine citrus orchards and crops of sweet potatoes, squash and beans, as well as irrigated rice. They speak their own languages, observe traditional practices and celebrations, and elect leaders to the local and municipal governing councils.

Photo courtesy of LRC-KsK/FoE PhilippinesThis abundant water makes the Didipio valley perfect for terraced rice farming. Beginning in the 1960s, Indigenous rice farmers moved into the valley from neighboring provinces and built terraces. Some moved at the urging and with assistance from the governmental agency for Indigenous Peoples. Others were forced from their homes in the Agno valley by the construction of hydroelectric dams. Although they came to Didipio by force and through hardship, the Ifugao, Kalanguya, and Ibaloi peoples have made the most of Didipio’s clean and abundant water by producing fine citrus orchards and crops of sweet potatoes, squash and beans, as well as irrigated rice. They speak their own languages, observe traditional practices and celebrations, and elect leaders to the local and municipal governing councils.

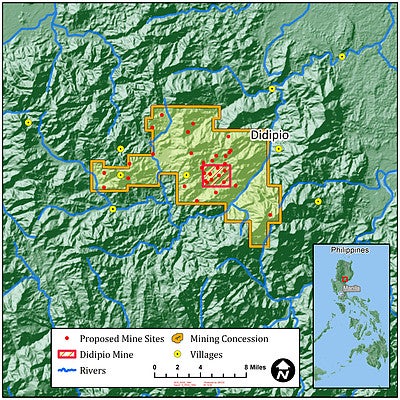

Since 1992, they have been fighting off mining companies. Their staunch opposition sent several companies packing, but the Australian Philippines Mining Company, a subsidiary of OceanaGold Philippines Inc (OGPI), has refused to let go of its concession on Mount Dinkidi, and it plans to mine neighboring mountains, too, that are the birthplaces of many other rivers.

Agriculture is Sustainable, so “No to Mining”

Photo courtesy of LRC-KsK/FoE PhilippinesOpen pit copper and gold mines use huge quantities of water as well as cyanide and other dangerous chemicals to separate copper and gold from massive volumes of ore—literally mountaintops. On Mount Dinkidi, the mining waste would be dumped into tailings ponds at the top of the Addalam River watershed, submerging 64 hectares (160 acres) of productive farm land in a region where suitable land for farming is scarce and highly valued. Managing mine waste in a region prone to torrential rains and typhoons is risky. Many tailings ponds in similar conditions have suffered leaks and spills resulting in fish kills, crop failures, and illness in humans and animals. If a major spill were to occur in Didipio, the mine waste—comprising toxic chemicals, soil, and rock—could plunge down the valley and onward to the Cagayan River, affecting ecosystems and human communities for hundreds of miles.

Photo courtesy of LRC-KsK/FoE PhilippinesOpen pit copper and gold mines use huge quantities of water as well as cyanide and other dangerous chemicals to separate copper and gold from massive volumes of ore—literally mountaintops. On Mount Dinkidi, the mining waste would be dumped into tailings ponds at the top of the Addalam River watershed, submerging 64 hectares (160 acres) of productive farm land in a region where suitable land for farming is scarce and highly valued. Managing mine waste in a region prone to torrential rains and typhoons is risky. Many tailings ponds in similar conditions have suffered leaks and spills resulting in fish kills, crop failures, and illness in humans and animals. If a major spill were to occur in Didipio, the mine waste—comprising toxic chemicals, soil, and rock—could plunge down the valley and onward to the Cagayan River, affecting ecosystems and human communities for hundreds of miles.

Determined to protect the source and safety of their precious water supply, their homes and their sustainable economy, Didipio’s Indigenous Peoples have opposed the mine since the early 1990s. They exercised their constitutional right to petition the government for a local referendum on the issue. They voted against the mine in local elections. They nominated and elected government officials who oppose the mine, and indeed the local and municipal councils voted against the mine. They took their case to the Supreme Court. They blocked OGPI’s access roads. And in a report to the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on Indigenous Peoples, they described attempts both to bribe and intimidate them.

In return, the Philippine government posted a permanent military guard to Didipio—not to protect the residents, but to protect and assist OGPI as the company threatened them, forcibly evicted them, demolished houses and shot one landowner who tried to stop the company from bulldozing a neighbor’s home. A climate of violence, fear, discord and grief now dominates daily life in Didipio.

Good Laws, Bad Enforcement

In opposing the mine, the people of Didipio stand firmly on their rights, and their charges have now been echoed by the United Nations Committee for the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD). The Philippines’ 1997 Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act guarantees Indigenous Peoples the right to free, prior, and informed consent to industrial development projects that would affect them. In Didipio, the Indigenous people have not been consulted by the mining company, nor have they given their consent. The National Commission on Indigenous Peoples has failed to advocate for their rights under the act. The Philippine Local Government Code and the Mining Code also require the consent of local government bodies before mining projects can proceed within their jurisdiction. Both the local Didipio village council and the Kasibu municipal council have opposed the mine since 2002, and the provincial government withdrew its support in 2008 because OGPI had failed to pay its taxes. OGPI is under investigation by the Philippine Human Rights Commission for demolishing 187 houses in Didipio in 2008 without a legal court order to do so. Nevertheless, the federal government allows the miners to continue and provides them military support.

Philippine law is seemingly progressive in recognizing the rights of Indigenous Peoples. But CERD asserts and the facts show that the law is not enforced to protect those rights.

There is still a chance to stop the Didipio mine before operations begin and the worst environmental effects are felt. Before mine waste can flood their valley, the Didipio Earth Savers Association wants to generate a flood of international letters to convince the government to recognize their rights and stop the mine. Please send a letter to the president of the Philippines.