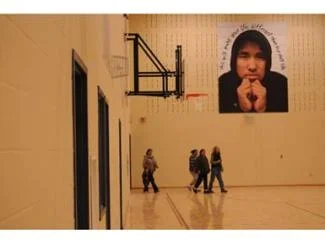

This month Cultural Survival's Endangered Languages program manager Jennifer Weston met with six Innu tribal members from Sheshatshiu, Labrador to discuss Native American language revitalization programs in the U.S., and the status of the Innu language in the Canadian provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec. Three students, two teachers, and a community-based artist from the Sheshatshiu Innu School visited Cultural Survival’s offices while taking time off from an exhibition they helped develop with the Phillips Academy Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts. Titled, “Pekupatikut Innuat Akunikana / Pictures Woke the People Up: An Innu Project with Wendy Ewald and Eric Gottesman,” the exhibit opened last month and runs through January 2013 as part of an exchange between Phillips Academy and the Sheshatshiu Innu School in Newfoundland and Labrador, where a large-scale banner exhibit is on display in the First Nation bilingual school that serves tribal students in both their mother tongue and in English.

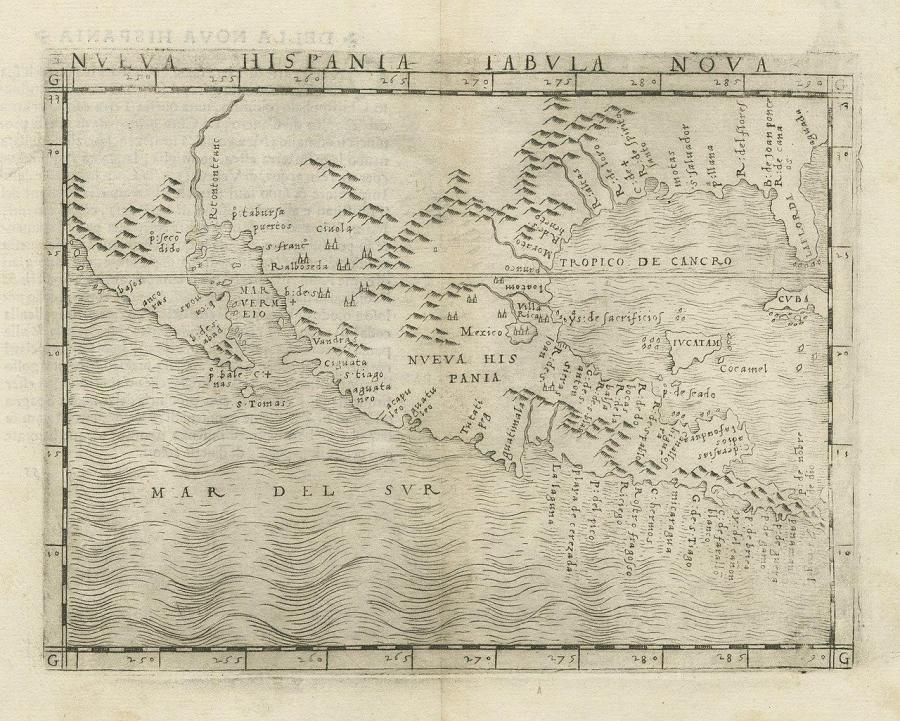

Sheshatshiu Innu Nation is located in the heart of Nitassinan, the traditional Innu homeland territories in Labrador and eastern Quebec. Innu means “human being,” and their language is called “Innu-aimun,” which is part of the Algonquian family of Indigenous languages. Most of the Innu in Sheshatshiu are bilingual, speaking both Innu-aimun and English. The Sheshatshiu reserve has a population of approximately 1,300 citizens, and is one of the two Innu settlements in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Innu language remains strong and spoken across the generations in both communities in Newfoundland and Labrador, and in the eleven Innu communities in Quebec. Students at the Sheshatshiu School receive the majority of their daily K-12 instruction in the Innu language, and English is also incorporated into a significant portion of their classes as well.

“We are just beginning to hear from a few parents—only a few—of concerns that their children need English-language instruction only to be more successful academically,” said teacher Kanani Davis (pictured, second from right).

Davis was interested in learning about the status of Cultural Survival’s partner language communities at the Alutiiq Studies Program on Kodiak Island, Alaska, the Euchee Language Project and the Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma, the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project in Massachusetts, and the Northern Arapaho Tribe in Wyoming. She and her colleague Jodie Ashini (pictured, third from left) were also eager to hear about best practices in language revitalization in the U.S., including attaining nonprofit status for community based language projects to insulate them from changes in tribal politics and elected government administrations, and incorporating language student, parental, and community wide volunteerism into language program models in order to offer no cost or low cost classes and language camps. Davis, Ashini, and their students also learned about the preschool immersion classrooms, college-level language studies, and master apprentice programs operating among the five partner tribal communities who have advised Cultural Survival’s endangered languages work since 2008.