By Febna Caven

Race is still an axis of exclusion in 21st century American public sphere. The symposium on "Racist Stereotypes and Cultural Appropriation in American Sports," held at the National Museum for the American Indian in Washington D.C. on February 7 was a comprehensive dialogue on this phenomenon. Divided into three separate sessions, enlivened by the presence of passionate social activists, intellectuals, politicians, religious leaders and a very vibrant audience, the symposium explored the history and politics of Native American imagery usage in sports and the case of Washington’s NFL team brazenly named as the “R*dsk*ns”.

Generic and specific Native American names such as the "Braves", "Indians", "Seminoles", and "Chiefs" are given by the dominant culture to many high school, college and professional sports teams in United States. Moreover, ‘comical’ or idealized facial imagery of Indians are still used as mascots of several teams and mock-Native American cultural practices including “war-whooping,” tomahawk chops, dances, and symbolic scalping still serve as game embellishments for spectators. The stories on the origin of these symbols and practices, told by their proponents are often very flattering, ascribing them to be tributes paid to exemplary Native American individuals or ways of being. According to Dr. Manley Begay, professor of American Indian studies in University of Arizona, these stories are nothing but myths and through these practices; Native Americans and their cultures are taken and remade into mass consumable stereotypes. Dr. Richard King, professor and chair of Critical Gender and Race studies at Washington State University, further elaborated on the effect of this fictionalizing, which creates an expectation of what Native people are like, an expectation that becomes so trenchant that, “The actual Native American finds themselves at a loss to embody those expectations.” This identity theft and recreation occurs for the profit of vested interests, while the Native American communities are left astray to deal with the consequences of such stereotyping. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a Northern Cheyenne leader and a former senator of Colorado noted, “Candy bars, beer and t-shirts named after us, benefit from us. They use our image for their profits, where we have 70-80% unemployment and our kids are hungry and where the suicide rates are more than anywhere in the country.” Commenting on the popular justification given by proponents of these practices that Native American names are often chosen not for profit or for discrimination, but for honoring them he further added, “'Bounty hunters', 'savages', 'squaws' are all terrible names. Who would want to be reminded of the time the bounty hunters claimed a prize against a piece of Indian hair or head… or be called a 'savage'… or be named after a part of a woman’s anatomy?”

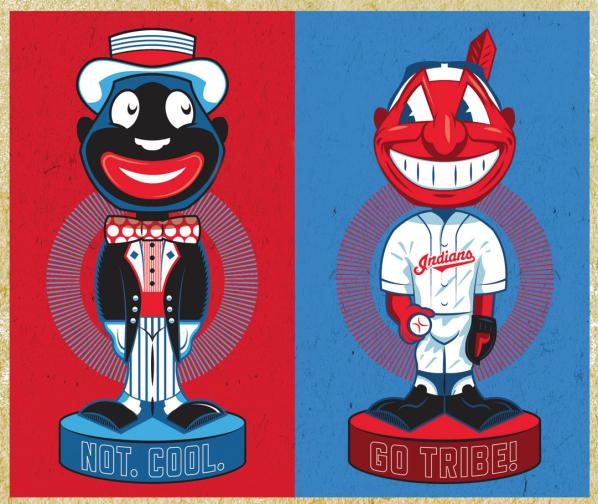

There is a strong polarization between mascot supporters who believe these images honor the Native people and opponents find only insensitivity and discrimination in their usage. One way out of this stale mate, according to Dr. King, is to look at the impacts of these mascots. As people create narratives that justify why they chose a name, it is necessary to look beyond “origin stories” to its actual impact on communities. According to Susan Harjo former executive director of National Congress of American Indians and founder of the Morning Star Institute, this impact can be seen starkest in children who take ridicule everyday as their culture and peoples are caricaturized and masqueraded as Dancing Reds and Chief Wahoo. The widely referred to research of Stephanie Fryberg who studied the effect of contemporary representations of American Indians on Native children’s psychology proves that it had detrimental effects on Native youth’s psyche. Often among the most-at risk in the school systems, Native children suffer from low self-esteem, low levels of self-confidence and community worth from the exposure to stereotypical imagery. The distressing experiences that Native American youth face in such environments were vividly described through personal experiences of many of the speakers. Dr. Lee Hester, director of Meredith Indigenous Humanities center, who is an alumni of University of Oklahoma which had Dancing Red as a mascot who danced to a tom-tom beat during games and Bruce Duthu, chair and professor of Native American Studies in Dartmouth College, which for many years sported a stereotypical Indian face as its emblem, shared their personal stories and how such mascots affected them and their college experiences.

There being no dearth for research evidence on the malfeasance of these practices, remarkable resistance in high school management boards, counties and states still remains to change the derogatory names and representations. O’Meally, director of governance and international affairs, National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) recounted the harrowing experience of receiving many death threats and hate mails following NCAA’s ban on discriminatory names for school and college teams. Dr. King remembered his grandmother, who, when the Indian mascot of the local school was taken away, asked, “Why would they want to take that away from us?” Dr. Ellen Staurowsky, professor in sports management in Drexel University, had an insightful comment on such blatant resistance to efforts to ban these mascots and names. According to her, casual stereotyping has become part of the country’s cultural currency. They facilitate the perpetuation of a very useful categorization of the Native American communities, one that allows the others to not be accountable for what was done in the past and thereby continue the marginalization. Seen in that way, these symbols and the myths surrounding them serve as opaque curtains, solid walls of white noise, that prevent the spectators from seeing the actual colonial history and from feeling guilt. Dr. Richard King further elaborated on how these mascots and names, which adversely affect the Indians’ self-esteem, actually give a boost to non-Indian’s sense of self-worth. Playing "cowboys and Indians" is an essential part of a child’s memory. To chip such experiences away and acknowledge that these are racist is a place, which according to King, no one wants to go.

The last session of the symposium, focused on the Washington NFL team name, "R*dsk*ns”, was an exceptionally lively community conversation where academics, sports columnists, residents of Washington stressed why the use of “R*dsk*ns” for the football team was simply unacceptable. Emphasizing how important the NFL team was to the community in Washington, Judith Bartnoff, a deputy presiding judge at the District of Columbia Superior Court, drew attention to disrespect the offensively named ‘unifying symbol’ of Washington brings to the community. She described the discomfort she felt, attending a game to root for her team, where she found the phenomenon of 90,000 people shouting racial slurs over and over and singing the theme song laden with racial references. Daniel Snyder, the owner of the team argues, the name was adopted in honor of “Lone Star” Dietz, a former coach of the team. Robert Holden, the deputy director of National Congress of American Indians, closed the last panel discussion with a response to such claims, stating firmly from his authority and experience, “Please. These are not honors for us. If they still insist on using them… Please, we don’t need those honors. Please we don’t want them”.

Washington R*dsk*ns, Cleveland Indians, Florida Seminoles and countless other school and college teams named Savages, Black hawks, Scalpers and Braves, are you listening?

— Febna Caven is an independent researcher and writer on communities in contested environments.