By Karen Smith

It’s 2020 and Japan has still yet to recognize Ryukyu/Okinawan Peoples as Indigenous or ensure their right to self-determination.

“That would be 500 yen” uttered the 20-something surfer with a naicha (Okinawa for mainland Japanese) accent demanding that our family pay for parasols at Nakagusuku beach on Miyakojima Island, where my family on my mother’s side come from. I will never forget that moment; the look of shock on my mother and my second-aunt's faces. The beach that they once knew to be untouched was now rammed with tourists and litter scattered everywhere. A hipster from the mainland peddling parasols and snorkeling gear from the back of his VW Van seemed to have now claimed that space as his own to commodify.

I thought going back to Miyakojima would cleanse my eyes and ears, tired and sore from the noise of Ospreys and the hideous display of U.S. military bases on Okinawa’s main island. Instead, I saw more of the juxtaposed landscape of pristine nature and militarism present on the main island. Military trucks and bulldozers passed by, on their way to clear lands for housing complexes and stations for the Japanese Army. They were adorned with the Imperial Japan flag, a painful reminder of Japan’s fascist past, but also a real reminder that Japan has not moved on but backwards, into the terrifying reality that many still live to remember, including my Grandparents.

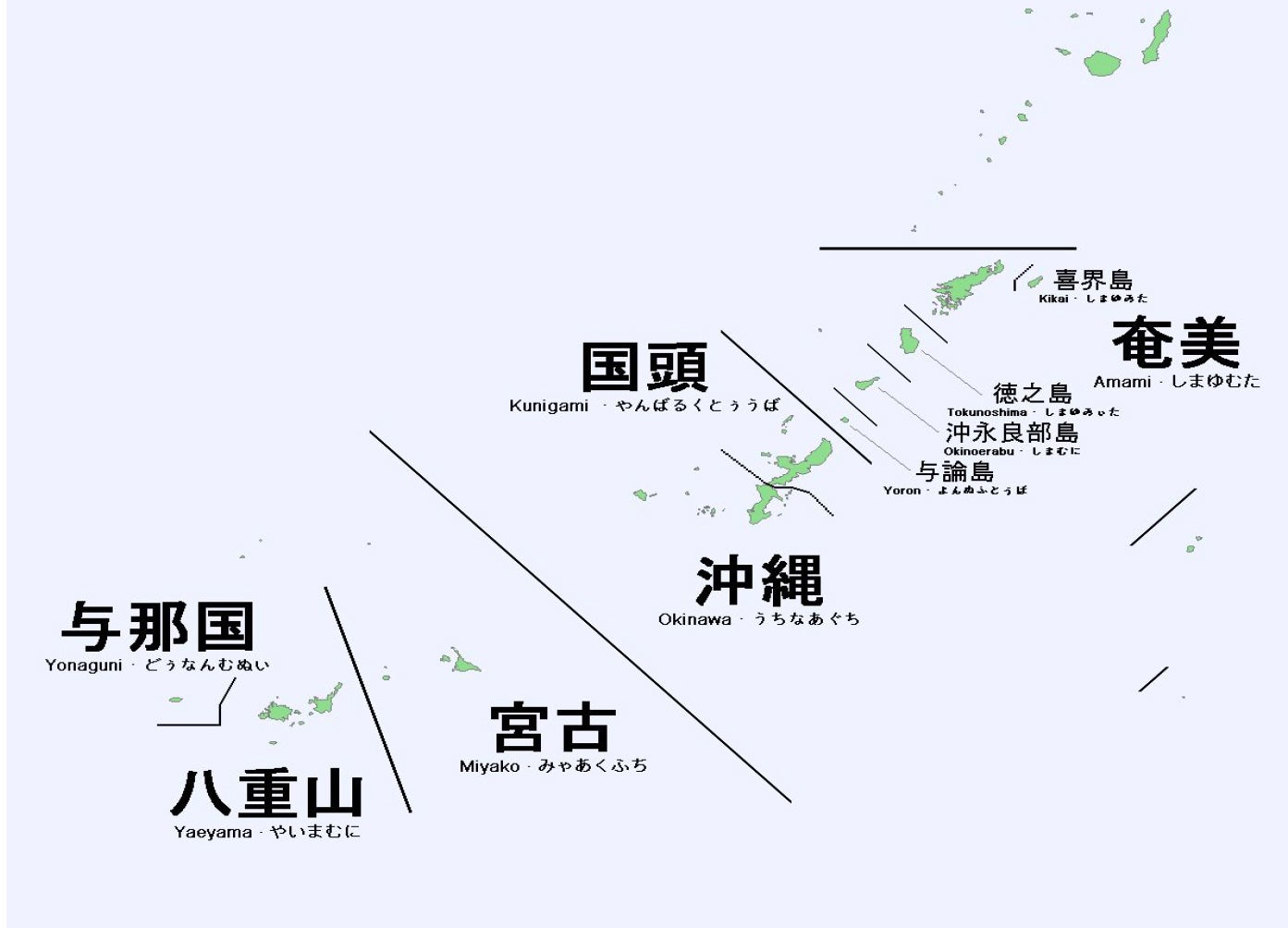

Formerly known to the Chinese as the “country of courtesy” the Ryukyu Kingdom (now Okinawa), are a group of islands who had its own bustling economy and served as an important trade route between South-east and East Asian countries. Made up of 150 islands, 60 of which are uninhabited, have various traditions, customs and languages that are distinct from one another but all share the Okinawan spirit omnipresent across the archipelago. Purveyors of diplomacy and peaceful inter-state trading, the Ryukyu Kingdom was an empire in its own right.

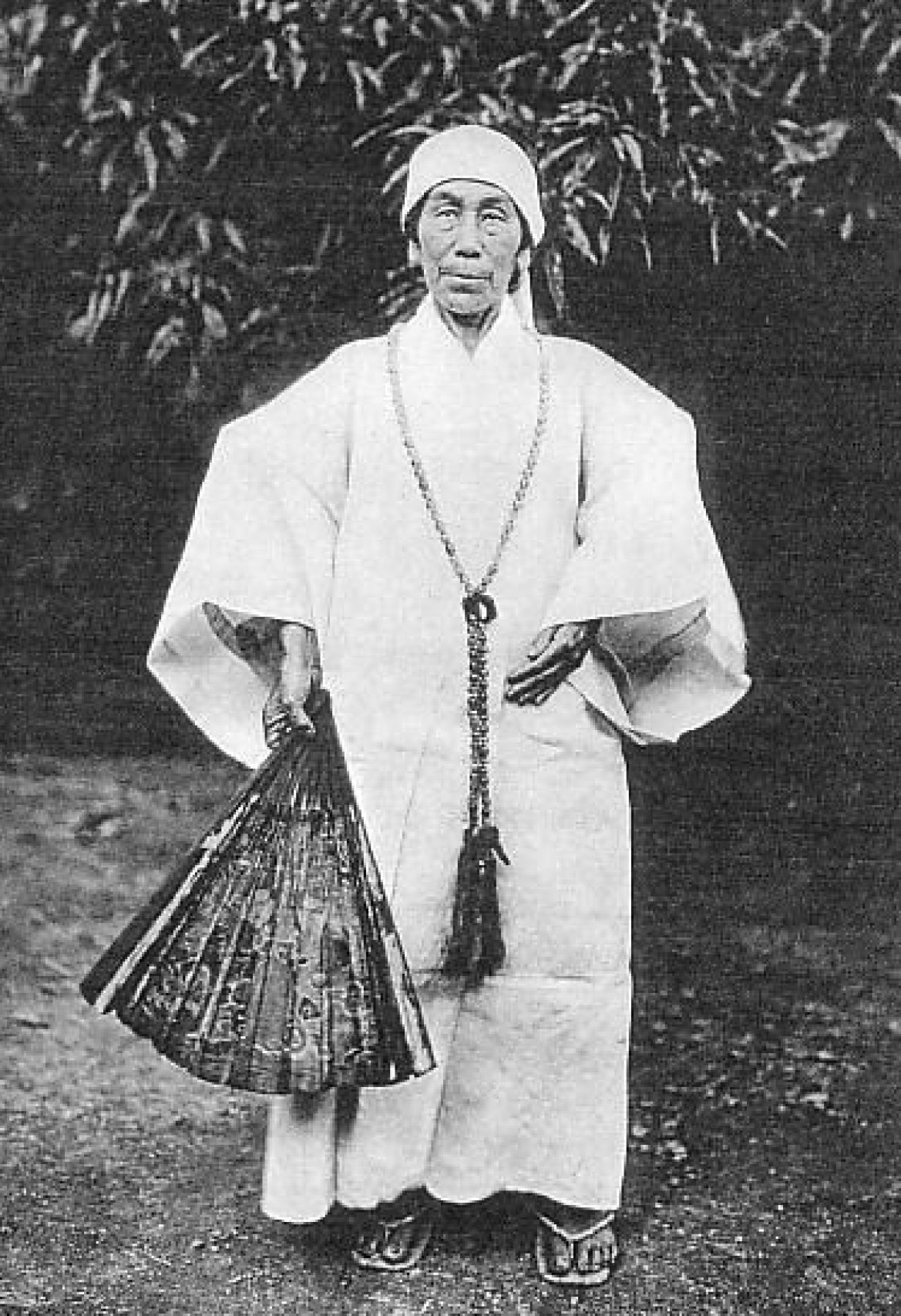

A priestess of the Ryukyuan religion, there were no priests, although male assistants were allowed to be present at ceremonies.

The Kingdom of the Ryukyus was subsequently annexed in 1879 during the Meiji Restoration and became Okinawa prefecture. This however, did not mean Okinawans were now Japanese, instead mere colonial subjects of Imperial Japan. My grandmother often recalls how she had to wear a hogen fuda, a heavy slab of wood around your neck as a punishment for speaking in Miyako. Ryukyu, Ainu, Africans and Taiwanese were among the many Indigenous people put on display at Imperial Japan’s Human Pavillion (Human Zoo) held in Osaka in 1903.

Human figurines of the many people put on display at Japan’s human zoo.

Fast forward to World War II, Okinawa was used as a buffer to fend off American forces attacking the mainland. To instill fear of the U.S. and foster allegiance to Imperial Japan, the Japanese Army convinced up to 700 people from children to the elderly to commit mass suicide. The lives of one third of the total population were lost to the war and rendered 90 percent of the population homeless. The Shuri Castle, once home to the Ryukyu Dynasty, was burnt to rubble. These memories are some that haunt people like my grandmother, who understandably, still cannot speak about them.

Japan “sacrificed” Okinawa not once, but twice: as part of Japan’s post-war peace process, full administration of Okinawa was given to the U.S. Being under U.S. authority, Okinawa was excluded from Japan’s post-War constitution as well as the U.S.’ obligation to guarantee human rights as it was not formally part of the U.S.. Twenty-seven years of U.S. occupation was fraught with human rights abuses against the locals with Agent Orange even being tested out as Okinawa was used as a base for the U.S. brutal war in Vietnam. After enduring 27 years of injustice, hoping that under Japan’s rule life would get better, Japan yet again betrayed the Okinawan people.

Currently, Okinawa holds over 70 percent of Japan’s U.S. military bases, but accounts for a total of just 0.6 percent of Japan’s total land mass. Our rainforest continues to serve as a ‘Jungle Warfare’ training center for the U.S. military. The gang-rape of a 12-year old schoolgirl by U.S. servicemen in 1995 prompted a referendum a year later, on the future of U.S. military bases in Okinawa. An overwhelming majority of 89 percent voted against it, but the central government was not legally obligated to respect the result. Ignoring the referendums is a regular occurrence. In February 2019, another referendum result which reflected the deep opposition Okinawans had to yet another military base being constructed, was ignored. The most devastating part of this is the fact that the new base is being built on Henoko Bay, home to two coral reefs, 300 endangered species and to the near-extinct dugong, which will all be destroyed all in the name of “security.”

The man largely responsible for the recent ramp-up in Japanese re-militarization is the same awkward man who wore a Super Mario costume at the Brazil Olympics closing show to introduce Tokyo as the next host city. His name is Shinzo Abe, the grandson of a class A war criminal who has repeatedly expressed desire in reverting Japan back to its sadistic, imperial state it once was. In his first term in office, he ordered that Japanese history textbooks should remove passages which mention Imperial Japan forcing Ryukyuans to commit mass suicide. He also continues to call the hundreds of thousands of Asian women whom were forced into sexual slavery by Imperial Japan as “comfort women.” To highlight the extremity of his beliefs, Mein Kampf was recently greenlit to be used in Japanese schools as “teaching materials.”

A poor effort

Abe dressing up as an iconic Nintendo character was not about celebrating Japan’s creative innovations. It was however, a carefully crafted move to cover up Japan’s disastrous failure in reconciling with its own history and allowing the world to perceive it as having “moved on” from the past.

In the words of Frantz Fanon, “The immobility to which the native is condemned can only be called in question if the native decides to put an end to the history of colonization.” Perhaps that is why Japan does everything possible to veto any efforts made by Okinawans and refuses to recognize us as Indigenous, as that would automatically give us the legal right to claim back the lands that were forcibly taken from us.

Whilst the free movement of people remains a heavily scrutinized and over-reported topic, the free movement of nuclear weapons, military bases and overworked foreign workers across islands in the Asia-Pacific such as Okinawa goes widely underreported. Absence of the voices of Okinawans as well as Chamorros, Naurans, and Hawaiians are the reason why Indigenous futures remain uncertain and are close to being pushed over the precipice of fascism and climate devastation.

-- Karen Smith is a native Okinawan, SOAS Development Studies Grad & Social Worker in training, based in the UK. Currently learning Miyaafutsu, an endangered language of her native Island, Miyako.

Top photo by Daniel Ramirez.