By the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Newton Committee, Allies, and Network***

In 2021, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the date of the Boston Marathon was changed from April 9 to October 11—Indigenous Peoples Day—without consultation with local Indigenous Peoples in Massachusetts. After much advocacy from local Indigenous leaders and organizations including Indigenous Peoples Day Newton, and the town of Brookline who withheld a permit for the Marathon to pass through its town until the conflict with Indigenous Peoples Day was addressed, on August 27, 2021, the Boston Athletic Association, the organizer of the Boston Marathon, issued an apology. “In selecting the fall date for the Boston Marathon, the Boston Athletic Association in no way wanted to take away from Indigenous Peoples’ Day or celebrations for the Indigenous and Native American Community. We extend our sincere apologies to all Indigenous people who have felt unheard or feared the importance of Indigenous Peoples’ Day would be erased. We are sorry,” stated the Boston Athletic Association. The BAA also responded to Indigenous leaders agreeing to acknowledge Indigenous lands that the marathon is crossing, committing to donating to the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Newton Committee’s efforts to organize the first-ever Indigenous Peoples’ Day Celebration in Newton, as well as recognize Indigenous athletes participating in the 125th Boston Marathon over race weekend and on Indigenous Peoples Day.

Land acknowledgment is an important first step to uplift Indigenous Peoples and build awareness about historical and contemporary Indigenous struggles. Following the lead of the Boston Athletic Association, other institutions and organizations can elevate Indigenous presence through land acknowledgments, as well as taking steps to seek justice through actions that champion Indigenous sovereignty, rights, and well being.

Over the past several years, land acknowledgments and #landback advocacy have begun to educate the public about Indigenous Peoples, their histories, colonization, marginalization, dispossession, and injustices, and also have started to guide people towards a more authentic relationship with the land and with each other. Land acknowledgments can be a starting point to build bridges between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. Education about Indigenous issues, histories, and rights within companies and communities is essential to building relationships that place justice and healing at the forefront.

What do land acknowledgments actually mean? And what do they mean to Indigenous Peoples? Annawon Weeden (Mashpee Wampanoag and Narragansett), who works closely in cultural revitalization and activism, reminds us that these issues demand more than attention, they demand action. “Land is all we have. For us as Indigenous Peoples, identity is pulled from the land, identity relies heavily on the land. I find meaning to connect with spaces that I come from. I want to give knowledge to homeowners that Indigenous Peoples should have access to what is needed on the land and not see land as commodity, but as informing identity,” Weeden says.

In discussing the role of land acknowledgments, Weeden says they “are a great opportunity but a bit trivial, as Indigenous individuals cannot separate identity from land; what makes me who I am is the land.” Weeden explains, “Mashpee means ‘great water.’ Great water is part of my identity in its abundance and diversity. What water produces, i.e., ecosystems, is a precious resource. Mashpee is part of the greater Nation of Wampanoag, a collective of Tribes that claim People of the First Light, the light that hits this continent. It is my role being from this Tribe to honor the waters and the light. It is both privilege and responsibility. The sun doesn't have to come back, therefore I honor the sun.”

Love Richardson, Tribal leader and enrolled member of the Nipmuc Nation and of Narragansett descent, shares her thoughts: “Bones are in the ground. As Indigenous people we need to help re-Indigenize our communities, let them know our ancestors' bones are in the ground, prayers are in the water. As stewards of the land, we need to acknowledge we are also stewards of the water, the Nipi. We are connected to our Indigeneity through our DNA that never goes away, and must be awakened.”

She continues, “I am Nipmuc, people of the freshwater, land of many ponds. We pray at water, we make treaties at our water’s edge. Much like the land, water ceremonies are important to our people, just as much as they are for every Tribe. Our Ancestors' prayers and tears are shed in the waters, blood continues to be spilt because of the lack of water. It is a living element and has legal rights in Canada. Water has memory, as does the land.” She added a valuable question: “What does it mean for allies to hear a land acknowledgment? Land acknowledgments are more so for allies, a tool for educating. While I believe that they are necessary when treading upon land or water where we are visitors, the ancestral ways were not in a speech of ownership but of community, exchange, ceremony, courtship.”

The recent trend in performing land acknowledgments indicates there is interest among the wider public to understand and learn how to honor Indigenous Peoples. Land acknowledgments can be one step towards standing up and standing with Indigenous Peoples. Richardson recalls a time she witnessed a land acknowledgment in Massachusetts so powerful that onlookers shed tears, having been previously unaware of the close relationship Indigenous Peoples have with the land, ignorant to the atrocities performed by colonial settlers. At that moment, allies were created and existing allies fortified their fight. Land acknowledgments have the power to center the interconnectedness of land and people, to pay tribute to the original stewards of the land.

“Indigenous people need allies and the Boston Athletic Association could become our ally. We need allies to make something for the greater good of Indigenous Peoples. We need allies to correct the history of the colonized thinking of Indigenous folks as ‘savage.’ Land acknowledgments open doors for understanding,” Richardson says.

Much work needs to be done, and Richardson believes the place to start is the school system. “Having a platform is huge, no matter if corporations or other institutions like universities. Voices are being heard through land acknowledgments.”

While some are already aware of the devastating effects of colonization on Native Peoples, there are still many that are unaware or choose not to know. Land acknowledgments are an opportunity to cultivate awareness and listen closely to the stories that have been excluded from textbooks. The notion that Native Americans exist only in the past is an intentionally crafted story written and told by colonial settlers as a way to uphold white supremacy and limit awareness of what actually happened to Native American Tribes. Primary and secondary education frequently omits Indigenous narratives, culture, and history. False narratives pervade the pages of books, painting erroneous images of Native Americans and insinuating that they were erased from the land or simply disappeared. Yet, Indigenous Peoples are still here. They are part of our contemporary communities, they live and work in cities, and they merit more than a few pages in a history book under the Manifest Destiny sub-chapter. Indeed, a new bill in the Massachusetts legislature, promoted by Indigenous, leaders aims to address the lack of Indigenous representation in public school curriculum.

Indigenous Peoples in New England and across the continent were, and continue to be, displaced, if not by colonial settlers then through environmentalist conservation strategies or extractive industries. Native children were stolen and placed in residential schools as a form of cultural assimilation under the motto, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” From broken treaties and massacres to erasure culture through white facing narratives and lack of inclusion or representation, Indigenous Peoples have endured the brunt of colonial settlers' aim to advance their land acquisition no matter the cost. Indigenous bloodshed earned military medals in “wars” that are only now finally being referred to as what they were: massacres. Until 1978, it was illegal for Indigenous people to practice their spiritual ways. Even the burning of sage could incur a prison sentence. Now Sephora and Urban Outfitters, white-owned and operated corporations, sell sage, commercializing and appropriating Indigenous practices.

By stating, “You are on Indigenous land,” awareness is raised. It is an opportunity for Indigenous Peoples to be seen and a chance for non-Indigenous people to hear the truth of what has happened to many Peoples and Nations. This matters now more than ever, as the Boston Athletic Association chose to hold the 2021 Boston Marathon on Indigenous Peoples Day without consulting Indigenous Peoples. Had they consulted with Indigenous folks, they would have known how sacred this day is.

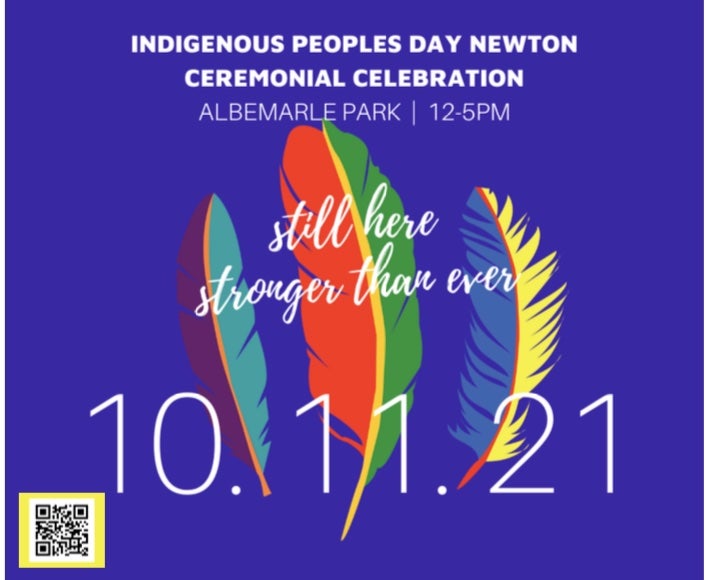

Indigenous Peoples Day Newton Planning Committee, led by Dr. Darlene Flores (Taino) and Chali’naru Dones (Taino), has been tirelessly working to uplift Indigenous Peoples Day and also bringing awareness to the Boston Athletic Association. Indigenous Peoples Day is an opportunity to share Indigenous histories and experiences. It pays tribute to Indigenous Peoples’ lives in the wake of Christopher Columbus’s brutality. For years, a culture of erasure has stolen Indigenous presence. The Boston Marathon route runs through several cities and towns (Wellesley, Newton, Brookline) that have officially recognized Indigenous Peoples Day, thanks to tireless efforts of local organizers including Indigenous Peoples Day MA. Notwithstanding, all of Massachusetts is Indigenous land. Some see the Boston Marathon date change as a blessing in disguise. “Now we have the opportunity and platform to make Indigenous Peoples visible during a globally televised event,” members of the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Newton Planning Committee resound.

The Boston Athletic Association can seize this moment as one of learning, growth, restitution. Along with their athletic sponsors, Weeden suggests going further than issuing an apology by creating scholarships to help future Native runners. It would be a “small gesture, saving youth by giving an out and hope, a saving grace for Indigenous youth.” Nike is one company that has taken steps in this direction. They’ve implemented N7 products that support Indigenous communities by teaching kids to be leaders and warriors. “Sports are a way to prevent drugs and suicide. Natives like Jim Thorpe have been leading the way in acknowledging that you’re doing business on Indigenous land and allowing Indigenous folks to excel. Indigenous runners haven’t been given the resources or the exposure to these experiences like privileged folks have,” Weeden says.

If the Boston Athletic Association and athletic companies are truly ready to commit to Indigenous Peoples’ justice and freedom, Weeden says they must “integrate their words into action.” He suggests donating shoes and funds for training as a starting point. On land acknowledgments, Weeden says, “if done more, they could bring to light the reality of Indigenous identities and give the opportunity to present basic knowledge of Indigenous landscape and identity in a global/geographic context.”

Larry “Wampiniquin Wampatuk” Fisher (Mattakeesett Tribe), member of the Indigenous Peoples Day Newton Planning Committee, offers a final perspective as it relates to non-Indigenous people failing to meaningfully consult with Indigenous Peoples, “Over the centuries, there has been denial of access to legal avenues that secure and defend Indigenous rights. Laws to protect Indigenous people are not enforced, or the legal process required in order to benefit from them is prohibitively difficult. Indigenous Peoples must be able to exercise sole right to self-determination on ancestral lands and inherent right to inherent sovereignty, and to do so without any external interference.”

Fisher calls people in, asking for inquiry on deeper levels so that Indigenous sovereignty goes beyond theory and becomes integral to Indigenous lives. “There must be more innovative ways to address issues, otherwise we risk falling back to tired, old patterns that no longer work and do not uplift Indigenous people. We need funders to decolonize dollars by stop putting funds into places that cycle genocide. Non-Natives must critically think beyond what they are already used to doing, being, and thinking; an honest, radical revolution with Indigenous folks at center.”

Why do land acknowledgments matter?

1. They recognize systematic oppression.

Engaging in land acknowledgments is not about blame, but rather recognizing how systemic and institutional systems have been oppressive to Indigenous Peoples. Oppression has affected how Indigenous people are perceived by non-Indigenous Peoples. And how non-Indigenous People interact with Indigenous Peoples, even today.

2. They honor Indigenous lives.

A land acknowledgment is a first step in paying homage to the Indigenous land keepers in the region. The land has been, and continues to be, shaped by their cultural knowledge practices before colonial settlers established themselves. There is no distinction between land and body.

3. They are culturally significant.

Colonizers’ primary relationship with the land is ego-driven and extractive, and the many current place names in Massachusetts, for example “Myles Standish State Forest,” or “Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park” celebrate individuals that have committed atrocities. Indigenous names, however, oftn highlight ecological and cultural significance for Indigenous Peoples. They are signposts, guides, and homages; indicators of the sacredness of land for Indigenous Peoples.

4. They highlight errors and gaps in environmental protection.

When National Parks, (dispossessed Indigenous lands), were established and protected, governments and conservation groups viewed Indigenous Peoples as obstacles to be removed. Indigenous Peoples were forced out, excluded from using land they had previously relied on for food, cultural materials, and traditional practices. As a result, Indigenous ecological and cultural histories of sacred ecosystems were stolen from them. Indigenous displacement is a consequence of environmental protection.

5. They signify access.

Indigenous Peoples’ food sources, pharmacies, classrooms, and places of worship, as well as Indigenous languages, cultures, and ways of being, depend on access to uncontaminated lands. Their identity is intrinsically tied to the land.

6. They honor Indigenous land management.

Indigenous Peoples manage one-quarter of the Earth’s land, which contains 80 percent of global biodiversity. Collaborating with Indigenous Nations to support Indigenous land management practices will facilitate biodiversity conservation. It is less expensive for governments to invest in Indigenous land management practices in National Parks than current programs related to enforcement, restoration, and biodiversity initiatives.

7. They continue community connections.

It is important to build relationships with our neighboring Tribal Nations who were removed from their lands (what are referred to today as our public lands). Land acknowledgments are relevant and imperative as we pivot from a world that has tried to erase Indigenous Peoples from the globe. Until the original land stewards are returned to their roles, harmony and balance will still feel distant.

8. They are a first step in reconciliation and healing.

Land acknowledgment is a first step. Returning lands back to Indigenous Peoples, resourcing Indigenous-led efforts, and uplifting Indigenous leadership are important immediate next steps.

Further resources:

https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/informational/land-acknowledgement

***This article is the result of the collaboration and work of the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Newton Committee members and allies. The Committee consists of a Working Group including members from the following Tribes: Mashpee Wampanoag, Aquinnah Wampanoag, Narragansett, Nipmuc, Stockbridge Munsee, Delaware Lenape, and Taíno. Jacklyn Janeksela, Indigenous Peoples’ Day Newton Committee Public Relations and Marketing Director, made the article come to fruition. IPDN Committee wishes to thank, honor, respect, and mention all Tribes and individuals who made this possible.

Image: Charles River by slack12.