By the beginning of the 19th century, during the colonial rule of Portugal in Brazil, there was a general, common Indigenous language spoken by numerous Indigenous Peoples as a second language in northern Brazil, parts of Venezuela, and Colombia with some similarities to languages spoken in Paraguay. Some historians say that the Indigenous Peoples themselves, mainly Guarani and Tupi-speaking, created this language. Others say that it was a language created in partnership between the Tupinikin and Guarani Peoples and the Jesuit priests. Already in the first century of colonization, some literary documents such as letters, plays, and poems were written in Nhēēgatú. Banned at the end of the colonial period and considered extinct by many, today the language is seeing a revitalization. Cultural Survival’s Lead on Brazil, Edson Krenak Naknanuk (Krenak) spoke with Indigenous writer and teacher Yaguarê Yamã Araranguá (Maragua/Satere) from Amazon, Brazil, who teaches the language to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

CS: Tell us about the origins of the Nhēēgatú language.

Yaguarê Yamã Araranguá: Nhēēgatú is an Amazonian language that originated from the Amazonian Tupinambá Peoples, particularly in the Maranhão region. From there it expanded into the entire Amazon basin and influenced the speech of many Peoples. It belongs to the Tupi-Guarani linguistic family. For centuries it became a lingua franca among Indigenous Peoples, and was spoken even by non-Indigenous Blacks, whites, criollos, etc. The initial grammar started to be codified by Franciscan priests in the 16th century. It briefly passed as the official language of the Amazon Republic created by the cabanos, the Indigenous and Black revolutionary movement that was quelled by the mid-19th century. Its name comes from the words that mean “speak well,” or “speak beautiful.”

Nhēēgatú was prohibited for two moments in Amazonian history: first, by Portuguese ruler Marquis de Pombal, in order to give way to the Portuguese language around 1778, then in the mid-19th century after the Cabanagem Revolution (war for the independence of the Amazon 1835–1840) led by Indigenous Peoples and Maroons. The punishment for using the language could be prison or even execution, and was treated as a crime of treason. Today it is spoken in addition to the caboclos accent by at least 10 Peoples in various regions. I’m proud to be speaking and teaching this language.

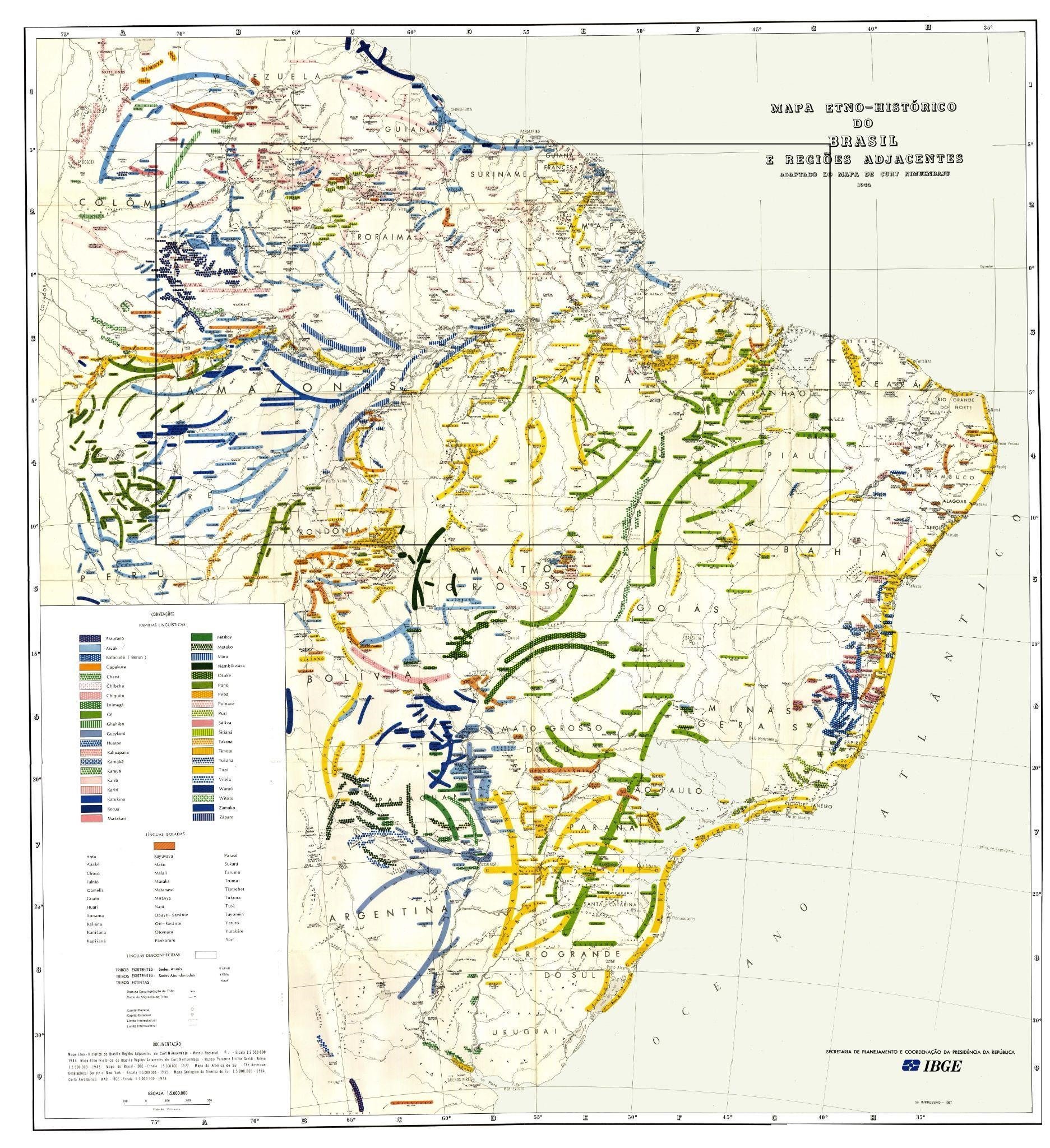

Coverage of uses during the colonial period in the historical ethnolinguistic map of traveler Curt Nimuandaju (German/Guarani) (adapted - 1944). Source IBGE/Brazil

CS: Is Nhēēgatú the same as Tupi?

YYA: No. Tupi is a language with various dialects spoken by groups living in the Brazilian coast during colonial times, especially Tupinambá. The Tupi language in the Amazon changed over time, gaining Amazonian characteristics and its own accent. Today, for those who understand Tupi, there is reasonable difficulty in understanding Nhēēgatú. The modern Tupi has many colonial interferences and a rigid grammar. Nhēēgatú was never a natural evolution of Tupi.

CS: Is there only one form of Nhēēgatú?

YYA: No. There are at least four spoken and written forms among Indigenous communities. The Nhēēgatú from Venezuela is little known among Brazilians. The Nhēēgatú from the Rio Negro is also called Yēgatu. The traditional form of Nhēēgatú is still spoken in the lower Amazon and lower Madeira regions in the state of Amazonas, and the Nhēēgatú from Tapajós is still used by Tapajoawara Peoples in the state of Para.

In the Rio Negro region, there was the influence of the Arawak languages that took away the use of u and y (e/u). Today there is also the absence of the use of nh. In the lower Amazon, the old Nhēēgatú remained more linked, maintaining the nh, o, and a little use of the y in Tupi. The permanence of words collected by Stradelli is observed in 70 percent of the words with their own characteristics, such as the use of Ç. In the region of Nova Olinda, the influence of Sateré on the language and also of the Arawak language and Maraguá is a differentiation. In the Tapajós, from the old records, one can see the maintenance of the words collected by Stradelli, but with orthographies closer to casa novae, in addition to having an influence of yēgatu through learning in courses for teachers in the Río Negro.

CS: How is the language being strengthened and revitalized?

YYA: An academy for the language is being created, the first in Brazil and Latin America, which intends to regulate the three spellings of the three variants recognized by the speakers and by the public schools where it is taught. The forum headquarters will be in the city of Manaus, with 23 seats divided among Indigenous and non-Indigenous speakers. Teaching it is the best way to strengthen the language.

CS: Is Nhēēgatú official anywhere?

YYA: It is a co-official language in the Amazonian municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira in the northwest of Brazil, which is the most Indigenous city in the country. It has recently become an international language with the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) through the Motorola phone project, where it has become one of the language options on the cell phone.

CS: How can people start learning Nhēēgatú?

YYA: In addition to a Nhēēgatú course offered by two or three universities, today there are several posts and places on the internet; it may be the most well known Indigenous language in Brazil. There are some published dictionaries of Nhēēgatú created by Indigenous teachers in the Amazon region. Also, WhatsApp groups have been created by Indigenous and non-Indigenous teachers teaching some aspects of the language, especially pronunciation.

Kuekatú reté (thank you).

Top image: The classic by Antoine Saint-Exupery, “The Little Prince,” translated into Nhēēgatú.