By Polina Shulbaeva (Selkup, CS Consultant)

On June 6, 2022, the Bonn Climate Change Conference (SB56) began its work in Bonn, Germany, in preparation for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP27) meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change established an international environmental treaty to combat "dangerous human interference with the climate system", in part by stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. The Bonn Conference will run through June 16.

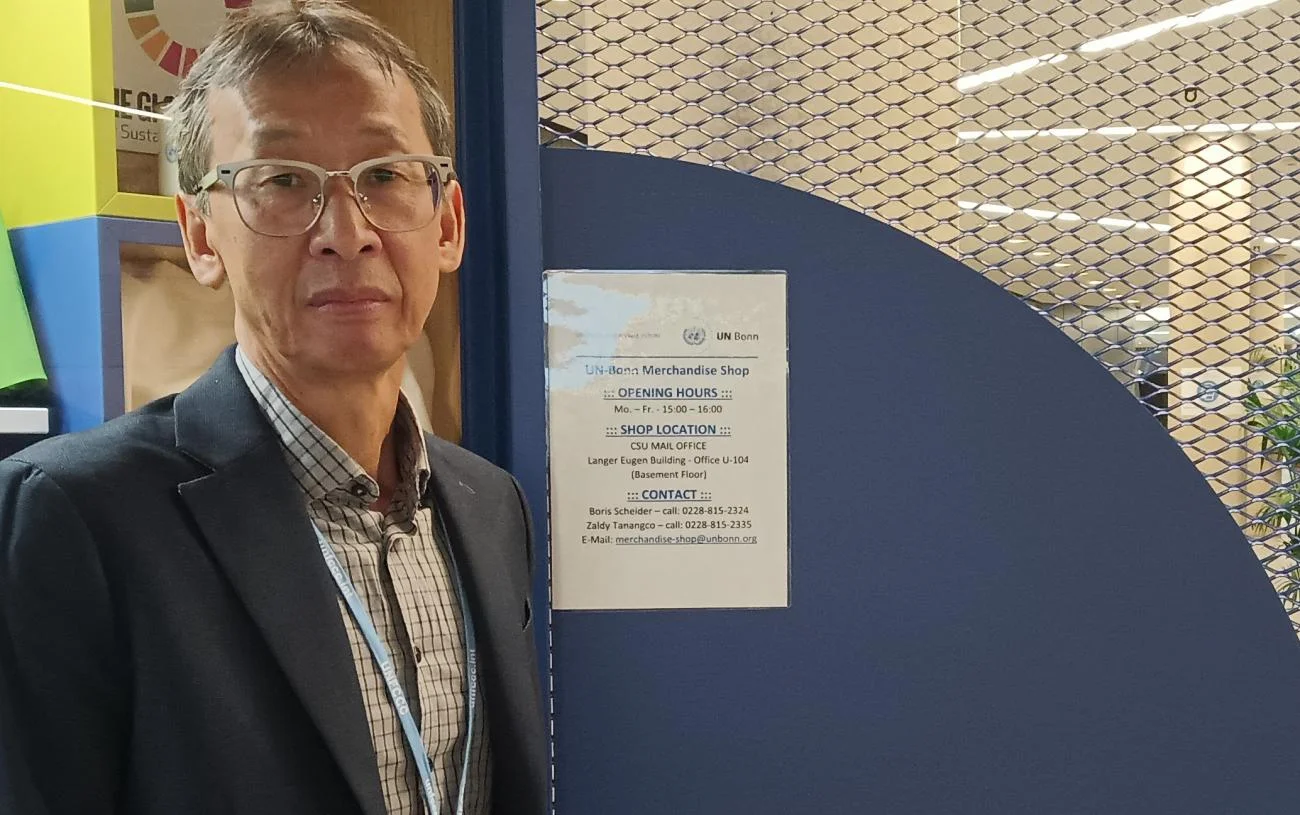

Indigenous delegates are at the forefront and participating in this work and negotiations, advocating for and promoting their rights and interests. Today, Cultural Survival spoke with Rodion Sulyandziga, a representative of the Udege Peoples living in the Far East of the Russian Federation about the ongoing negotiations at the Bonn Conference.

Polina Shulbaeva: Thank you for agreeing to this interview, Rodion. We will start at the national level. Please tell us how climate change is affecting Indigenous Peoples in Russia?

Rodion Sulyandziga: It's already a global problem which affects not only Indigenous Peoples, but all Peoples, countries, and continents. Indigenous Peoples are the most vulnerable to climate change for numerous reasons. They continue to live in harmony with nature, relying on natural resources, and these are precisely the places where climate change is most evident. The impacts of climate change explicitly affect their entire lives and, above all, their traditional ways of life, and traditional economic activities.

On the one hand everyone says, including scientists, that the Arctic is the most vulnerable territory in terms of climate change and approximately one-fifth of Russia's landmass is north of the Arctic Circle. On the other hand if you look at national policy, Russia was the last country to join the Paris Agreement just a few years ago, and is just beginning to develop internal national documents and legislation on climate change, adaptation, mitigation of threats and future losses. There is a sense that climate change is not a priority for the Russian Federation. An endless number of events and large meetings take place only in capital cities, while leaving out the municipalities and local communities that observe climate change impacts and face its consequences every year. We see how everything is becoming more and more unpredictable in terms of natural disasters, forest fires, floods, melting permafrost, epidemics, etc. Climate change also affects infrastructure security for houses, buildings in the North. For planning, even for oil and gas pipelines, and industry - this is such a complex problem, which of course is discussed at high levels, but without Indigenous Peoples’ participation. We need to do a lot to ensure that Indigenous Peoples are fully involved in negotiations, participation, and decision-making, along with climate scientists, environmentalists, and government authorities at different levels. Indigenous Peoples hold knowledge that can be useful when we talk about adaptation to climate change. This can be seen in our national platform, which was initiated by Indigenous Peoples.

PS: Please tell us more about this national platform.

RS: The Paris Agreement created the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP) at the global level, which has been running for three years now. It was created to strengthen the knowledge, technology, practices, and efforts of local communities and Indigenous Peoples to address climate change. We had the idea to create a national platform in Russia to connect it with the global one. We worked for three years on a pilot project, focusing on the Arctic and the Saami Peoples in the Murmansk region. We held many meetings and trainings for local people and Saami people, and we developed manuals and tools in collaboration with scientists. We created an online platform, which is multilingual and easy to use both on the Russian level and on the global level. This project is an opportunity for other territories in Russia to hold similar events and develop their own plans based on the specifics of their territories and traditional knowledge. The platform can also help those who want to work on adaptation, education, integration of Indigenous Peoples and their traditional knowledge in climate change work. This was a unique experience for us and shows how Indigenous Peoples themselves can work on this topic.

PS: Today is the start of the Bonn Climate Change Conference designed to prepare for COP27. Why is Indigenous Peoples' participation so important in such events?

RS: The problem remains that there are big gaps between what is happening locally, nationally, and internationally. All decisions and all major discussions leading to decisions take place in capital cities and at such international events, therefore it is important for Indigenous Peoples to be direct participants in the negotiation processes. Within the global climate change negotiation process, Indigenous Peoples are one of the strongest self-organized groups and have a strong voice and leadership. This significant presence and push for participation can be seen in the experience of the Paris Conference and previous events and COPs. Even though Indigenous Peoples have the status of observers with no voice in decision-making at the UNFCCC, we have our own structure, the Indigenous Peoples' Forum on Climate Change (IPFCC), represented by participants from seven regions that work very coherently and dynamically, and monitor all the negotiations and dialogues within the negotiation process. Hundreds and thousands of participants come to these meetings: politicians, scientists, and representatives of different groups and stakeholders who are trying to find a consensus on different topics. In the meantime, time is running out and it is necessary for decision-makers to understand the gravity of the situation. I would also like to see more private sector participation because it has a major impact and influence on nature and consequently on climate change. When everybody is at the table, except for the private sector, and if we are talking about industrial activity, their absence from the negotiating table does not contribute to overall success.

PS: What are the most important topics for Indigenous Peoples at this meeting?

RS: Today, we have 5-6 key issues that we will work on. These include the human rights-based approach under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, the subsequent carbon market mechanism, and the issue of financing, especially potential financing for Indigenous Peoples and local communities. Direct access to finance for Indigenous Peoples and local communities remains a major issue. As we heard at COP26 in Glasgow, funding will be allocated, but there is a need to make the finances directly available to Indigenous Peoples. It is also important to mention thematic issues such as loss and damage, climate change adaptation and mitigation, general implementation of the Paris Agreement, and other areas. Climate issues are linked to biodiversity, deforestation, food sustainability, and many others, and unless nations take real steps and solutions to reduce emissions, we will all face serious climate consequences and for the most vulnerable groups, such as Indigenous Peoples. It will be catastrophic. Indigenous Peoples have always lived in harmony with nature and all the recent climatic, environmental, and other problems are only adding to the risks Indigenous Peoples face. It is important for us to stand and fight for our land rights, because if we manage to preserve nature as it is, then there is a chance for the survival and development of Indigenous Peoples themselves. We are already facing this planetary challenge. Therefore, it is necessary for us to fully participate, to be at the table, to fight, and continue to stand up for our rights to climate justice for Indigenous Peoples.