By Jerome Gerald Kujur (Oraon) and Isha Savani

“We will give our life, but not our land” is the slogan of the Netarhat movement and the expression that binds 32 different Indigenous communities spanning thousands of acres of land across the Netarhat mountain range in eastern India. Since public spaces to discuss Indigenous struggles are quite rare in India, it was an honor to speak with Jerome Kujur, an activist and scholar from the Oraon Indigenous community of central India.

The Netarhat movement was officially founded in 1992, in response to the Indian government’s proposition of repurposing native land for military activities. Two hundred and forty-five villages encompassing 3000 square kilometers, or four times the size of New York City, were to be evacuated, but no one knew where to. Kujur was studying at the local university and was in his early 20s at the time when the rumors of permanent displacement reached his ears. He and his fellow students had begun to unionize in his early college days and were also the first generation of people from his community to receive higher education, who were not as fearful of the State as the generation before, and who understood the machinery under which the State operated. Armed with the legal language to say ‘No,’ they organized under the Jan Sangharsh Samiti (JSS) [committee for the people’s struggle], which ended up leading one of the longest non-violent movements of post-independent India.

The foundations of the JSS can be traced back several centuries. The Indian military’s plan of occupying villages in the greater area of Netarhat mountains was laid out in 1938 and was an eventual outcome of land laws that had been executed between 1700-1800 under British colonial rule. In post-colonial India between 1965 and 1992, the Indian army’s practice grounds encompassed seven villages. The JSS was founded when in 1992 the government proposed expanding this ground to 245 villages with the aim of permanently evacuating 250,000 inhabitants, continuing the treatment of Indigenous communities as entirely disposable. During these three decades, the army would appear two to three times a year without prior consultation with the community leaders, often giving notice mere days or even hours before starting artillery exercises which would continue for weeks at a time. People were expected to evacuate to the neighboring forests during this period, regardless of the extreme heat in summer or rains in the monsoon. They would rush back home to prepare meals at erratic times of the day whenever the army would take a break from firing.

The few schools that were present in the region had to be closed during the firing exercises, and children were occasionally offered 0.75 Rs (less than $0.01) as daily compensation for the disruption to their education and lives. Organizing food and shelter was left to the villagers, and each resident was offered a meager compensation of 1.5 Rs a day. Several Indigenous community members either worked in farms or had their own farms. As the army trucks bulldozed their lands while destroying their crops, they lost their livelihoods, and the government’s “compensation” was far from what they needed to sustain themselves on.

Kujur spoke pensively about his relationship to this land, and whether anything would possibly compensate for permanently leaving his ancestral home. “This place is called the Queen of Jharkhand,” he said. “We believe we come from the Indus Valley civilization. According to the legend our princesses fought against the Mughals disguised as men and succeeded in repelling them thrice. They lost the battle to the Mughals in the fourth encounter, which led to the displacement of our Peoples to Jharkhand.”

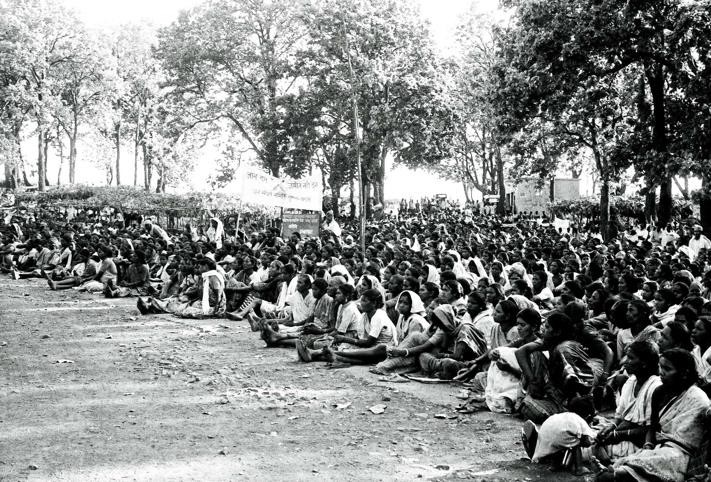

Over the years, the disparate Indigenous Peoples met each other in the region of central East India and came in close contact with the people who were exiled from mainstream upper caste Indian society for generations, known as the untouchables. The Indigenous and other marginalized communities welcomed each other and blended in while maintaining their individual languages and associated professions. Kujur believes that the common struggle for land rights and basic human dignity is what brought them together. The JSS consisted of representatives from each of the 245 villages who coordinated protests across the affected area and established communication lines between the local village level administration all the way up to the center in New Delhi. One of their most effective protest methods was to form human chains as barricades encompassing the villages to prevent army vehicles from trespassing. The largest such action happened in 1994, consisting of 150,000 protesters who had come from beyond the affected areas in a show of solidarity. When asked if any of them were armed, Kujur answered simply, “We were allowed knives only when cooking.”

The military has not been seen since 2004 after 12 years of intense protest and a decade-long campaign to keep the army out. However, protests alone did not dissuade the military from the region. The JSS members reached out to different layers of the political hierarchy. They wrote in the local press, they wrote to officials higher up regarding the ongoing military intervention, and invited leading politicians to have dialogues with representatives from the army, together with members of JSS. At one such meeting, the JSS presented statistics on a total of 402 casualties suffered as a result of the military activities, including the number of people who had died because of misfiring (30), incidences and casualties related to rape (86), those who had become disabled (3), those who had been victims of petty crimes from the army, like the theft of poultry (26), the number of houses destroyed due to misfiring (7), the number of places of worship destroyed (1), the number of instances of destruction of agriculture (225), the number of cattle that died as a result of misfiring (24), and the number of trees destroyed in the wake of military practices (uncountable). The violated members of the community were also present at the meeting to give a firsthand account of the horrors that they had faced in the years ensuing the firing practices. Kujur believes that history was in their favor on this occasion. The chair of the meeting was appalled at the evidence presented and ruled that the army’s presence was unconstitutional.

Since that meeting, the army’s exercises have been suspended in the region and the government has postponed its decision on permanently displacing the 245 villages. Kujur still believes that the struggle is far from over. His decade-long research and activism have shown that the State will not automatically respect you and give you what you deserve and that you must fight for your rights alongside your day job, because, as Kujur said, “chanting slogans is not enough to feed your stomach.” Kujur earns his livelihood through a writing scholarship, and now only has an advisory role to the leaders of JSS. He recently completed a four-day march covering 152 kilometers as part of the ongoing campaign to pressure the State to resolve the Netarhat issue.

Jerome Gerald Kujur and his wife.

Around the world, the narratives for occupying Indigenous lands have shifted throughout the centuries. Early colonists justified occupying land which they considered as waste, uncultivated, and no man's land, despite the obvious presence of Indigenous Peoples. Over time, the justification for appropriating land has changed. The later colonial idea maintained that Indigenous Peoples should have the right to their land only after they have reached a certain degree of civility, where defining ‘civility’ was considered a prerogative of the aggressor. Today, narratives of development and national security are used to displace the Indigenous Peoples from their lands. The Netarhat case questions the idea that a nation can be made more secure and formidable at the cost of eradicating Indigenous cultures and peoples. By endangering the Indigenous livelihoods, their ways of being and knowing, including how to sustain and live in harmony with their environments, forests, and lands, the Indian government has become the agent of threat and insecurity in the name of national security.

The seeds of the movement were planted in 1938 under British colonial rule. Seventy-five years after independence, the Indian government continues the colonial trajectory leaving the Indigenous Peoples fighting the same fight as they did in pre-independence India. The Netarhat movement is still alive today, and the JSS has taken other ongoing land rights issues under its umbrella, each presented by the Indian government with its unique justification of national security, economic development, or wildlife conservation. When asked if he is afraid for himself and his people under the increasingly hostile current political climate, Kujur answered, “Of course I am afraid, but for how long can I be afraid? The movement is beyond me.”

-- Jerome Gerald Kujur (Oraon) is an Indigenous rights activist and author spearheading the Netarhat Movement in Jharkhand, India.

Isha Savani is a physicist based in Oslo, Norway, who is part of the International Solidarity for Academic Freedom India (InSAF India) Collective.