“Developing Stories: Native Photographers in the Field,” featuring essays and images of Native American photographers, is on exhibit at the New York City branch of the National Museum of the American Indian until March 12, 2023 and features the work of photojournalists Donovan Quintero (Navajo), Tailyr Irvine (Salish and Kootenai), and Russel Albert Daniels (Dine’ descent and Ho-Chunk descent). In addition to the online and in-person exhibition, on February 4 the museum sponsored “Fresh Focus on Native American Photography,” featuring the aforementioned photographers as well as art photographers Tom Jones (Ho-Chunk) and Nia MacKnight (Hunkpapa Lakota and Anishinabe), whose works are also on display. I spoke with Cecile Ganteaume, Curator of “Developing Stories,” and Daniels prior to the symposium.

Phoebe Farris: You have been generating a lot of visibility outside of the usual gallery and museum circles, such as a recent Washington Post article and its exposé about Native enslavement and loss of tribal connections. So many Native Americans deny or suppress any acknowledgement of Native American slavery. What made you willing to go public about Native enslavement?

Russel Albert Daniels: I grew up with stories about my ancestor Rose, who was enslaved. In school, history books left out the topic of the Indigenous slave economy, how the Spanish colonized the southwest and enslaved Native Peoples prior to English dominance and the creation of the United States. My ancestor Rose, who lived to be 104, was enslaved, trafficked, sold to a Mormon polygamous family, and eventually married her Mormon “owner” and had children by him. Later she was enrolled in the Ute Tribe in the 1800s. Her story is well known in Utah, but not in other states. Five generations of my family lived on the Ute reservation. As a teenager I wanted to dig deeper and learn more, so I eventually went to journalism school, studied history, did research, and visited New Mexico. I read books about southwest slavery and wanted to learn how to tell stories with photographs.

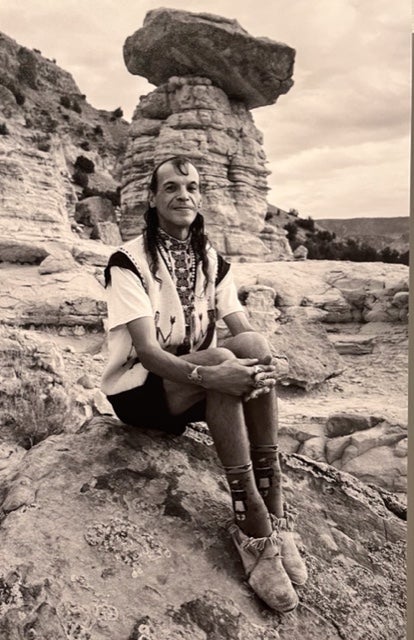

"Maurice Archuleta in the High Desert Surrounding Abiquiú." Photo by Russel Albert Daniels.

PF: In describing your ancestor Rose, you mentioned that she was trafficked north and legally sold to a polygamist. Trafficking usually refers to illegal sexual exploitation, so why did you state that Rose was legally sold?

RAD: Slavery was legal under Spanish rule and occupation. Most Indigenous slaves were purchased as enemy captives, mainly kidnapped in Ute and Comanche raids that took place along the Utah, Mexico, and California trade routes, also called the Ute Trails. In 1847, Mormons came to what is now Utah and created a law that legalized Indigenous slavery in 1852. It was legalized by Brigham Young and a Mormon legislator. During the colonial era, mainly women were taken captive in tribal wars. Utes and Comanches were the dominant slave raiders and sold the captives to Spanish settlers living in New Mexico.

"Pueblo Tools and Pottery Sherds." Photo by Russel Albert Daniels.

PF: How did Indigenous enslavement compare to African slavery during the same time period? Are Indigenous descendants of slavery such as the Genizaro seeking reparations similar to African-American slavery descendants?

RAD: Spanish slavery both predates and post-dates the African Atlantic slave trade, especially as practiced in southern states. When the southwest became American territory, slavery never really ended. During the 500 years of slavery, the legal language of slavery changed; the name changed, but slavery never really ended. Regarding reparations, the Genizaro are not interested in pursuing them.

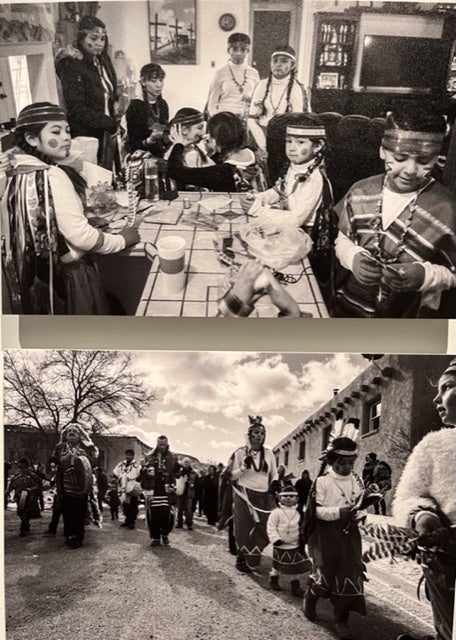

"Santo Tomás Feast Day Preparations and Festival." Photos by Russel Albert Daniels.

PF: As a person of Indigenous descent, how do you navigate the world of enrolled Native American artists, which can sometimes be exclusionary? Do you feel that overall you have been accepted into the community of Native artists and writers?

RAD: It has been a challenge. I grew up in a mainly Mormon, suburban Salt Lake City neighborhood. Some of my relatives are Mormon. Some of my relatives kept their Indigenous identity but are Christians and assimilated. Five generations of my family lived on the Ute reservation. For some there is a shared identity. There has been a recent shift about identity and Indigeneity, so there is more acceptance of ‘mixed Indians’ now.

PF: In addition to issues such as captivity, your work also explores through photography stories about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), Two-Spirits, Standing Rock, and Bears Ears. Of these issues, which ones have personal significance for you?

RAD: For me, Bears Ears is personal because I grew up in Utah. The MMIW crisis is important to me because it is a continuation of trafficking Indigenous women, just like my ancestor Rose. There is a possibility that women who are not murdered or abandoned on the road are being sold for sexual exploitation. Trans people are also trafficked and victims in the MMIW crisis. Their status is now being recognized and the name Relatives is used for them.

PF: Do you feel equally comfortable in the visual world of photography and the more cerebral world of writing/journalism? Is it difficult to be a writer and an artist?

RAD: I feel equally comfortable. Many creatives do not like to write. It is hard and takes a deep level of concentration. It is important for visual artists to be able to write about what they create and put it into words. Also, artists have to write to get funded. Some visual artists are not natural writers. When artists do write about their own work, they begin to understand it on a deeper level. It requires deep introspection and can be rewarding.

"Santo Tomás Feast Day Preparations and Festival." Photo by Russel Albert Daniels.

PF: What other projects are you working on now or in the future?

RAD: My new project is about the Great Salt Lake and its drought. It has shrunk to one-third of its original size. The shorelines are contaminated with arsenic and metals that blow into the air and into our lungs. Three rivers have tributaries that feed into the lake and nearby agribusinesses, especially alfalfa farming and livestock, are causing pollution. I have been working in the field and am collaborating with US News editors on a 500-word photo essay. I also collaborate with The New York Times, mainly their photography editor, Amanda Webster.

--Phoebe Mills Farris, Ph.D. (Powhatan-Pamunkey) is a Purdue University Professor Emerita, photographer, and freelance art critic.

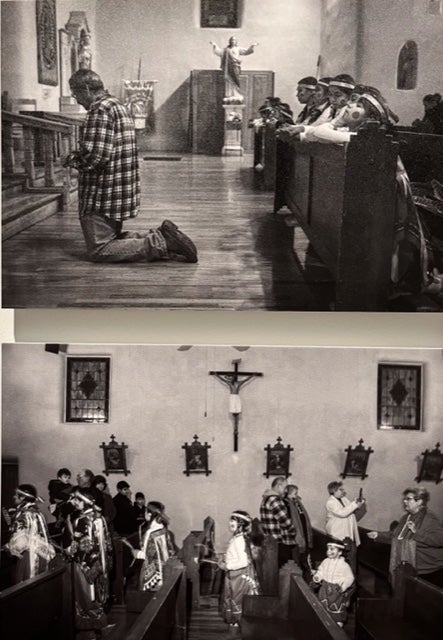

Top photo: "El Cautivo Dance." Photo by Russel Albert Daniels.

Read: Developing Stories: Native Photographers in the Field

Read: Interview with Cecile Ganteaume, Curator of NMAI’s “Developing Stories”