Imagine walking through a museum in Japan and seeing a glass case containing a bronze plaque with the words inscribed on the surface, “George Washington slept here in 1776,” with the explanation that this bronze plaque was an important part of American history. As an American, you would assume that something had been lost in translation. So it is for a lonely rock that was formerly set on the side of an ancient dirt road in Plymouth, Massachusetts, labeled “Sacrifice Rock,” along with its bad translation, “Manitoo Assun.” A better translation would be “God’s Stone.” Like the bronze plaque that commemorates an inn that once sheltered George Washington, this stone itself was not important, but the place it marked. When the Pine Hills Development started building in the largest undeveloped woodlands in Massachusetts, they carefully moved the stone and placed it in a new location with signage explaining the reverence Native people had for the stone. Something was lost in translation.

With development and industry, when big investors decide they want a resource, they move without regard to what would be lost. When concerns are raised about potential ways their plans could cause harm, often representatives of the investors come up with quick easy solutions that seem to lack fundamental understanding of the problems. From the Mayflower Pilgrims noting their Native guides through to myself in 2002, Wampanoag people have put offerings on the stone in recognition of the sacredness of the place. But since it was moved to a new location, I have had no reason to stop or make offerings. When the stone was moved, what was lost is lost forever.

The pine barrens in southeastern Massachusetts are under a similar threat from developments, but more so from sand and gravel mining, real estate, and so-called “green” energy development. The unique environment of the pine barrens has been formed over thousands of years; the delicate balance of the ecosystem includes the smaller plants, the animals, and the chemistry of the soil. The sand serves as a filter for the groundwater underneath. This aquifer serves as drinking water for residents, something that is irreplaceable.

Water is the foundation of all life, from the grasses up to the trees and the birds that live in the branches, and us, human beings. But the great lie of corporate personhood has created an abomination, the idea that a company can have legal standing as if it were a living, breathing person. But the corporation does not breathe, it does not love, and it does not need food or water. Its only sustenance is the bottom line.

Today in America, we have two classes of people: the lower class human person, and the elevated class of the corporate “person,” who has more rights and less accountability. Often the extracted resources are exported and the profits from investments rarely stay in the zip codes—if even the nation—they are extracted from. If, for example, the groundwater for the townspeople gets ruined, it may even be seen as an opportunity for corporate interests to maximize profits with solutions like selling bottles of drinking water, as we have seen for years in locations like Flint, Michigan, or Navajo reservations. But for the townspeople who gain no benefit from those profits, once the water is gone, it's gone. When it is lost, it is lost forever.

The land mass labeled ‘The Great Lot” was taken from Native people through the act of ending common ownership, allotting acreage to families, and then annexing the “surplus.” This method of claiming Native lands was common practice in the 1800s.

The pine barrens in Plymouth once connected from just south of Boston out across Cape Cod, before the Cape Cod Canal was dug out in 1910. When the canal was cut, it cut right through the traditional territory of the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe. There are stories passed down from generations that a burial ground was unearthed to make way for the canal, and that remains of colonial descendants were moved while Native remains were simply ground into the dirt and loam. Of course, there is no documentation of this, but the industry norm of the early 1900s was to disregard Native graves; this is the reason for the Native American Graves Protection Rights Act, which was enacted to give special protection in the face of continued violations.

Where a narrow creak once winded through the woods, a 480-foot canal now separates the Cape from the mainland, consuming hundreds of acres. Vast tracts of land were also taken in ethically dubious deals by Makepeace Properties, which have been a major supplier of cranberries for Ocean Spray. The company has vast acreages of bogs and wetlands and has been shifting from cranberry production to gravel mining. In that process, the access of Tribal officials to monitor new excavation has been denied by Makepeace, who contends that they can conduct their own monitoring for Native cultural sites. In spite of having no expertise in how to identify Native cultural sites and no representatives from the Tribal people, work has been approved. As a stakeholder with interests in development, they are in no way an impartial actor and have a vested interest in archeological evidence not delaying projects or impacting their bottom line.

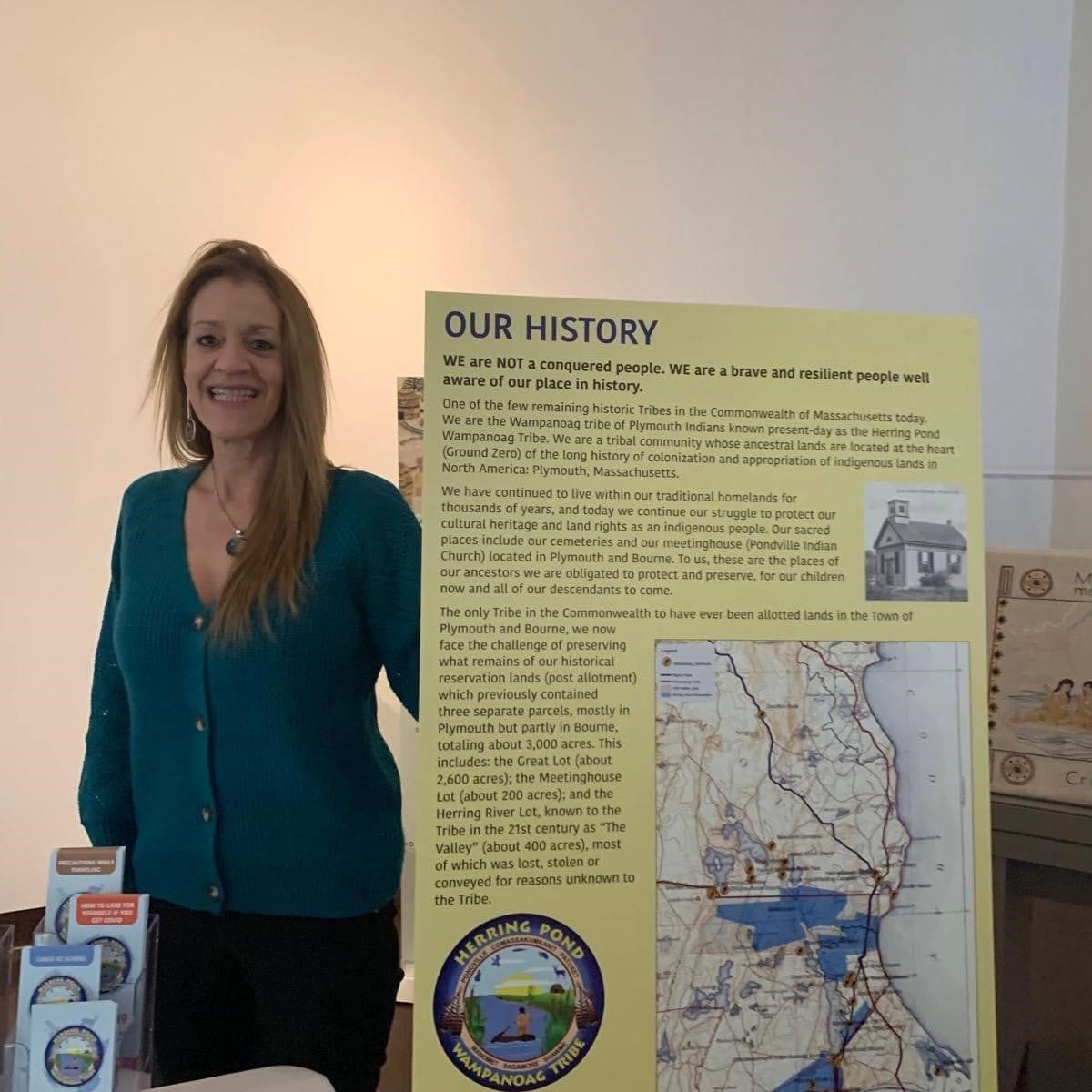

Melissa Ferretti in action, advocating for her Tribe. Photo courtesy of Melissa Ferretti.

Melissa Ferretti, chairwoman of the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe, has been an outspoken advocate for the interests of her community and the traditional territory they steward. “The homeland of Tribal Nations in the U.S. are among those communities that are most likely to be targeted for projects that are disastrous for the environment and that have multiple destructive impacts on Indigenous Peoples’ lives,” says Ferretti in regards to the ongoing development in the pine barrens. “The Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe knows this because we have been at ground zero of colonial resource extraction for over 400 years. For over 400 years, our ancestral lands have been clear-cut, stripped of sand and gravel, mined, and paved over.”

In the town of Wareham, Massachusetts, a proposed 20-acre solar farm is one of the local sites of development in the pine barrens. Up and down Fearing Hill Road you can see neon green signs that read “Don't Kill Fearing Hill.” The proposed site is in the middle of town conservation land but the developers want an exemption for “green energy,” claiming it is environmentally positive. This is how greenwashing works. The cutting of trees is ignored because solar energy is not oil. But that approach is reductive and narrow. Once the land is developed and the title is taken out of conservation, how many years until the solar farm is replaced with a building?

The location is one that is rich in Wampanoag cultural use. Also in the territory of the Herring Pond Tribe, the stream that runs through the area is the site of a herring ladder and a place our people would traditionally go to take these fish in the springtime. The site also has an Ancient Way, or a road of Indigenous origin, where Indigenous people have maintained the right of way from time immemorial. Wareham resident Kuwah Deetz (Mashpee Wampanoag) says of the project, “The town has so many other lands that can be used for solar panels that you don't have to cut down trees. There are parking lots and roofs of school buildings that can even help create shade for cars and reduce surface heating. Why do they need to do it here?”

Kuwah Deetz at Refinery Corridor Walk in 2015. Photo by Hartman Deetz.

If we continue to bend to the profit motives of the insatiable corporate persons, enough will never be enough. Did the townspeople bend to the will of the non-living person of Frankenstein's monster? Of course not. They took care of one another and confronted the monster by the strength of numbers; they joined together and drove out the undead to save the living. The needs of the global marketplace are like the needs of the undead. The corporate person is a quiltwork of dead material, of oil, sand, gravel, gold, lithium, who lives on quarterly profits. Much like the idea that the value is in the stone or a bronze plaque, the real value is often lost in translation. Water is life. It is irreplaceable. We must look at the needs of the living and let the dead bury the dead.

--Hartman Deetz (Mashpee Wampanoag) has been active in environmental and cultural stewardship for over 20 years. He is a traditional artist as well as a singer and dancer, having shown his art in galleries and performed for audiences from coast to coast across the U.S. He is currently a 2023-2024 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence.

Top photo: Provincetown Coastal Pine Barrens. Wikimedia Commons.