A twenty-minute car ride north from the city of Taitung, Taiwan, is the Indigenous village of Taoyuan, often referred to in the Bunun language by Indigenous residents as Pasikau. Pass under the village gate and a newly opened 7-Eleven, the Pasikau Presbyterian Church, a sprinkling of breakfast joints, and the occasional dog and neighbor precede the route to Niwa Maibut’s childhood home, situated on the corner of the Pasikau village now home to nearly 1,300 residents.

Niwa Maibut drives car from Taitung to Pasikau village.

Maibut, having returned to Taitung to live permanently five years ago, is now conveniently able to reconnect with a physical place she ventured off from at a young age while also maintaining her relationship with a culture and people she never left behind. Today, on March 18, Maibut gathers her bags from the car upon arriving home in Pasikau and heads inside after a vocal greeting to assist her mother in dressing for today’s Bunun Ear Shooting Festival (She’erji), a festival that takes place once a year in every Bunun village, once a year at the county level, and once a year across the entire island.Maibut wears a black, tight-sleeve shirt with embroidered piping, while her mother, Mua, chooses to pair her top with a long black skirt and a headpiece, decorated with metal jewelry and vibrant piping.

Maibut and mother, Mua, dress for the Bunun Ear Shooting Festival.

"If I’m going to attend, I must wear the full-body traditional dress," Mua tells Maibut. A wood-covered patio joins the Maibut family’s two homes together; one where her mother and sister, Ibu, live and the neighboring house where her sister-in-law and children reside. Maibut’s father, Adian, passed away before she was three years old and her brother, Adul, ten years ago, leaving the Maibut home fully female along with her male nephew. “Here, women are very powerful,” Maibut said. “Our women are encouraged to speak. In my village, we are allowed to say who we are.”

Maibut and her mother, Mua, in traditional Bunun clothing.

Maibut emphasizes a clear awareness of this power at a young age, influenced both by her mother and memories passed down of her father, but also internally fueled by a desire to connect with other people and places around the world. “I was brave when I was young,” she said.

Maibut’s teen years aligned with the lifting of Martial Law in Taiwan, a period of 38 years (1949-1987) in which the Kuomintang-led government implemented drastic and violent forms of security regulation throughout the island, including but not limited to the regulation of newspaper and magazines, the denial of free speech in any language but Mandarin Chinese, and the suppression and forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples and culture on the island.

The lifting of Martial Law in 1987, when Maibut was just 15 years old, opened a long road ahead for Taiwanese people, especially Indigenous peoples, while also allowing for Indigenous acknowledgement and emerging engagement of such identities with the outside world. “When I was little, a lot of people were helped by World Vision [International],” Maibut said. “People would line up at the church waiting for the gifts that had been sent. I would line up too, but none of the gifts ever had my name on them.”

Maibut laughs, noting that she couldn’t have received any gifts then because she hadn’t signed up for the program, as her mom often reminded her of at the time.“But imagine what it was like back then to get something from the United States, from Canada,” Maibut said.

Maibut drives ten minutes from her house to the site of today’s Bunun Ear Shooting Festival, a tradition that once served as a coming of age ritual for boys as well as an important hunting ceremony. Now, using guns rather than bow and arrow and stuffed animals rather than pigs, the ceremony serves as a way to remember and enact the history of Bunun people, for locals and spectators alike.

The venue for the 2023 Bunun Ear Shooting Festival.

“[The locals] practice their culture and make money out of it,” Maibut says of modern-day Indigenous ceremonies. “Not a bad idea, not a good idea, but that’s just how it has worked out.” Maibut’s response reflects what appears to be her stance towards life: preserve what you can, adapt to or change what you can’t. She stops at the entrance of the grass venue for today’s festival to vote on a referendum asking the government to approve an official name change of the village back to its original Indigenous name, Pasikau. Then she’s off to greet one person after another, including cousins, aunts, uncles and a handful of neighbors.

Between tutoring English in the evenings in Taitung and commuting to nearby villages three times a week for her job as a Green-Care Lecturer with Taitung St. Mary’s Catholic Hospital, where she leads locally and Earth-inspired classes for the elderly, Maibut still makes a point to return to her village every weekend, or more when possible.

In the Xiaoma village, Maibut introduces the benefits of burning a bunch of Asian mugwort atop a slice of ginger to help with blood flow.

Maibut’s connection to her village pays nod to a key principle she and her neighbors in Pasikau share: 全村共教養 (Quancun Gong Jiaoyang).

“If one child is successful or advances in a field, the entire community succeeds and was involved in getting them there,” Maibut translated. “It takes a whole village to raise a kid.” Success for Maibut, she acknowledges, was no different: a community affair with doors first opening for her through the help of World Vision International, a Christian humanitarian aid, development, and advocacy organization that first came to Taiwan in 1964.

“One day I just went to the [World Vision International] office in the village and asked how I could sign up, but they needed my mom’s signature,” Maibut said. She convinced the office her mom had approved and signed up that day. Years later, her mom chuckles about Maibut’s stubbornness, but never once objected to it. “I was lucky to have received help from so many different people,” Maibut said.

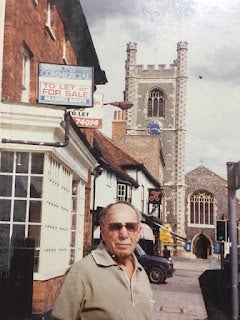

At age 10, the person who would most influence the next 20 years of her life was Arnold Anderson (above), a World War II veteran and native of England. Through World Vision International, Maibut received 50 Euros a month from Anderson, equivalent to about 2,500 New Taiwan Dollars at the time. But her future would soon be influenced beyond any monetary amount.

Waiting for the Bunun Ear Shooting Festival to begin, Maibut continues to mingle, quickly eyeing a group of international students sitting quietly in the stands; she approaches.

Maibut left Taiwan for the first time at 19, but what began as a trip to England soon turned into the next trip to India with her Presbyterian church, a summer trip opportunity to New York to study English education, weeks spent in the Philippines and the Southwest United States advocating for Indigenous rights on a global scale; and of course, visiting Arnold Anderson, who Maibut refers to as her “British daddy” and who her nephew is now named after.

“I was able to link my Taiwanese Indigenous identity with other Indigenous peoples,” Maibut said. “I was more like a hippie, but a very rational hippie,” Maibut says, who began to go by the name Jennifer at the time. “Back then, I thought I was Jennifer Lopez.” With a broader view of the world and increasingly better English language ability, Maibut followed the path her brother and sister, being too old for World Vision, never had the opportunity to; but, no one in Maibut’s family questioned her desire to go. “Like I said, I was brave when I was young,” she said.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in English from Christ College (Taipei) and being accepted to Long Island University (New York) in 1998, Maibut’s brother Adul sold off a piece of family land in order to pay for her tuition. “Now when I look back, maybe I was a bit selfish and naive,” Maibut said. But the many people she crossed paths with along the way feel otherwise.

Maibut mentions her friend, Heather (left), who first came to Taiwan for a summer exchange program in college and who Niwa then reunited with when she spent a summer at Geneva College (New York). This summer, Heather’s daughter will arrive in Taiwan under the guidance of Maibut, who will pass along a valuable characteristic of Bunun culture. “You always have a father or mother from different clans taking care of you,” she said.

At the festival, Maibut heads towards the group of international visitors and plops herself down in between two students who she soon learns are visiting Taiwan from Colgate University (New York). They have come to experience the Bunun Ear Shooting Festival, and Maibut makes sure to lean over and introduce each component of the reenactment as it begins, using her English language ability to build a bridge between two cultures. “Back then, I thought that I would like to be an English teacher,” Maibut said. “Early on, the desire was to be able to communicate with him [Arnold], and then he wouldn’t need to pay for a translator when he visited. Later, my motivation changed; I wanted to be a tour guide.” Never officially a tour guide, but always a bridge-builder, Maibut pulls from her previous and current experiences of life to educate herself and others.

Maibut speaks with a professor from Colgate University at the 2023 Bunun Ear Shooting Festival.

“He [Maibut’s dad] knew it would be hard for our people to live in the modern world if we didn’t go out to study and to explore; knowledge is power, knowledge is wisdom, knowledge is property,” she said.

Having visited 15 countries, Maibut has almost 4,000 friends on Facebook and holds a master’s degree in Teaching English as a Second Language from Long Island University and is currently working towards a certificate in social work and public administration. When her schedule allows, Maibut attends a Bible study lecture series at a nearby church.

Maibut attends a weekly Bible study in her village.

Those at the church wanted me to eventually help with some translations or English lessons, but I can’t use a language to teach what I don’t know, Maibut said. Though she herself is Presbyterian, she alludes to the more abstract theology of Christianity.

For Maibut, learning never stops. “I had a lot of thoughts back then, and I wasn’t afraid to listen to them and move on, I think that’s the key point,” she said.

In 2006, Maibut appeared in Oscar Kightley and Nathan Rarer’s documentary, “Made in Taiwan,” which explored ocean voyages of Pacific ancestors before their arrival in Taiwan. And in 2009, Maibut was featured in the film “Voices in the Clouds,” which follows Tony Coolidge, founder of Indigenous Bridges, on his journey to discover the Indigenous heritage of his deceased mother.

Maibut during the filming of "Voices in the Clouds".

“The more localized our efforts, the more globalized we can be,” Maibut said. “It isn’t just the West that can do so.” Maibut continues to welcome people into her home on a regular basis and intentionally seeks out ways to pass on the knowledge she has obtained from nearly forty years of global engagement. With the sound of a village member taking to the microphone, the 2023 Bunun Ear Shooting Festival officially begins and Maibut joins together with her neighbors and family members in a series of relay races.

Maibut poses for a picture in the middle of a relay during the 2023 Bunun Ear Shooting Festival.

“I am one of them [village member], but I have many elements in my life that are different,” Maibut said. Every Friday morning, Maibut drives to the village of Xiaoma, still in Taitung County, to lead a “Green Life” class with the local elders, sharing her knowledge of local products such as Asian mugwort. She dances around the room, naturally switching between Pangcah, Mandarin Chinese, and a bit of English, engaging a different age group in learning.

“Each course changes depending on where I am teaching it because people are different; the people are key,” she said.

Maibut still returns weekly to her home in Pasikau where a four-character sign hangs outside reading, 希望教室 (Xiwang Jiaoshi): Classroom of Hope. The task of passing on knowledge learned has long since been a family affair, undeniably influenced by Maibut. At this “Classroom of Hope,” run by Maibut’s sister, Ibu, local students in the village come on a regular basis to finish their homework and to continue their study of English.

“The way I see it, teaching English is how I give back to my village,” Maibut said. “At first, English was important because then I could talk to Arnold. Later on, after visiting other countries and seeing the importance of language, I saw English as my capital. With it, I can do many things: make money, make a living, make connections.”

The "Classroom of Hope" sign that hangs outside of the Maibut family home.