By Edson Krenak (Krenak, CS Staff)

During the second week of September 2024, the UN Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals delivered its report to Secretary-General António Guterres, outlining a set of principles, actions, and recommendations aimed at addressing equity, transparency, sustainability, and human rights in the extractive minerals sector. The document outlines many relevant recommendations but also shares why this new report has the potential to be a Siren song.

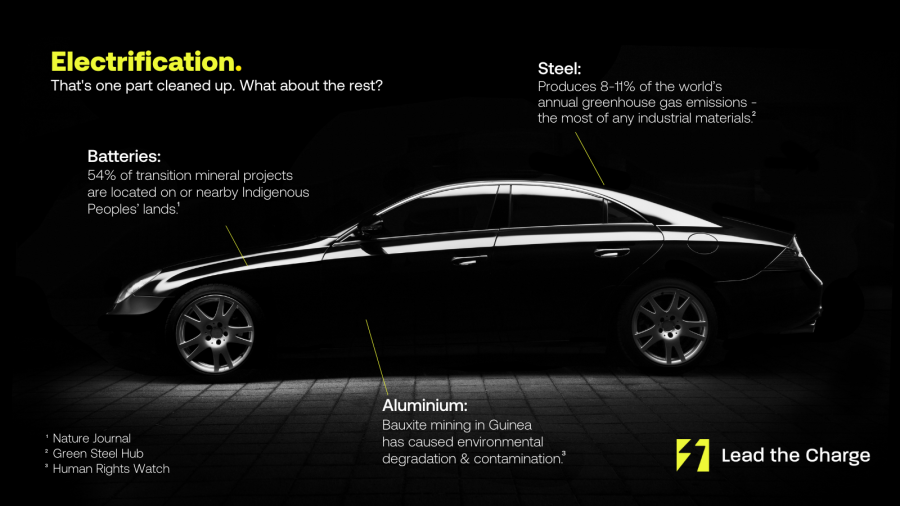

The Western world considers the so-called "transition minerals," which include copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements, essential for the rapidly expanding so-called clean energy sector, which encompasses wind turbines, solar panels, electric vehicles, and battery storage, among others. Demand for these minerals is projected to almost triple by 2030 as the world shifts from fossil fuels to renewable energy, striving for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Indigenous Peoples’ concerns are at the core of this discussion for two reasons: the colonial legacies of states and industries guiding their actions on the ground, and more than 50% of those minerals are in or near Indigenous Peoples’ territories if we consider peasant and other traditional communities, this number goes to 70%.

Launched on April 26, 2024, by Guterres, the panel is backed by a UN technical Secretariat and co-led by the Climate Action Team, UN Environmental Programme, and UN Trade and Development. It had input from 17 UN agencies, including the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

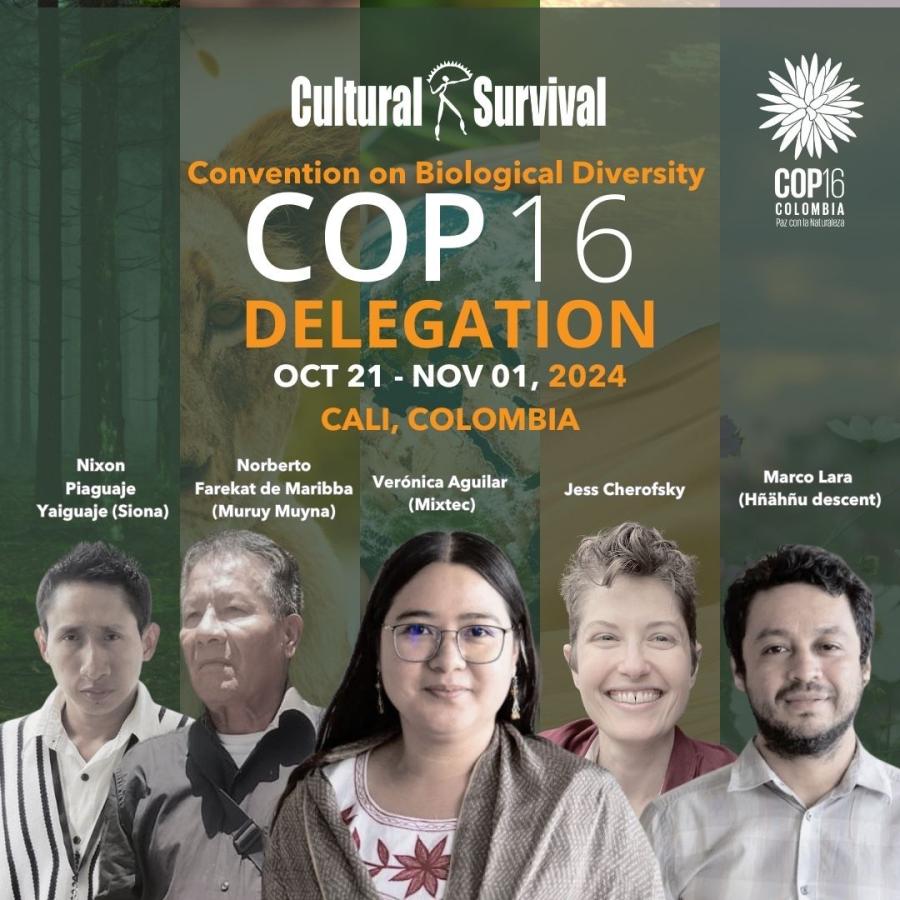

Cultural Survival and the Securing Indigenous Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition participated in several preparatory and public consultation meetings, where the four key thematic areas were addressed:

- Benefit-sharing, local value addition, and economic diversification;

- Transparent and fair trade and investments;

- Sustainable, responsible, and just value chains;

- Mineral value chain stability and resilience.

A dozen meetings took place to identify each area's priorities and build on the outcomes of the Guiding Principles and Actionable Recommendations. However, these recommendations, in spite of strong recognition of Indigenous rights that have the potential to translate into real protections for Indigenous communities, have an overwhelming focus on resource extraction, corporate-driven narratives of economic growth, and States being the protagonists.

The UN report, like many others, will be a "siren song" if it fails to serve justice to Indigenous Peoples. There are four reasons for failure:

- Colonial and anthropocentric language

The focus on Indigenous Peoples` rights is commendable as it highlights their stewardship over lands that are central to global biodiversity. However, the report’s language often reflects colonial frameworks, referring to Indigenous lands as "resource-rich" areas (“Indigenous Peoples, who are custodians and owners of mineral resource-rich lands.” pg. 07), defined by their abundance of metals like lithium, nickel or cobalt. This terminology reduces Indigenous territories to mere assets for extraction, neglecting the deep cultural and spiritual relationships Indigenous Peoples hold with their lands. Our lands and territories are rich in relationships, kinship, cultures, and natures. Seeing these as places for exploitable minerals is disrespectful to our worldviews, spiritualities, and epistemologies. The commodification of life cannot be a narrative that protects life and fights climate change.

2. Weak laws and recommendations mean more injustice

Another critical point is the implementation ambiguities surrounding the panel's recommendations. Yes, the report provides detailed principles and actionable recommendations, but its success depends heavily on political will and State cooperation. And we Indigenous Peoples know that the modern State - more than ever before - has strong commitments with industry and private interests undermining Indigenous Peoples’ rights and keeping the rate of violent engagement. The call for a global traceability framework and a High-Level Expert Advisory Group indicated by the report is essential, but the lack of binding mechanisms means these remain voluntary, and their effectiveness depends on the willingness of states and corporations to act. Since the 16th century, the softness of international laws and global frameworks have never prevented genocide of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, nor environmental destruction. We need new international global planetary laws. Without a clear enforcement, recommendations for benefit-sharing, environmental safeguards, and Indigenous rights protection will, like always before, falter and fail.

3. Lack of climate context

The report also lacks a clear strategy for resilience. For Indigenous Peoples, it is vague to talk about resilience without prioritizing prevention, adaptation to, and real compensation (reciprocity principle) for the impacts of the climate crisis on vulnerable communities, especially Indigenous Peoples. Although the report emphasizes the importance of a just transition, the document lacks concrete plans to address long-term climate risks and adaptation strategies to ensure that the transition is actually more just.

4. Use money with respect

Lastly, since the 2022 COP26 in Glasgow, the UN, States, and industries have promised a doubling of finance to support developing countries and Indigenous Peoples in adapting to the impacts of climate change and building resilience. But nothing happened because the language and the commitments were vague. Again, the report we are discussing provides vague financing mechanisms and limited attention to enforcement on corporations - the parties responsible for the vast majority of damage to the environment and impoverishment of our communities. The report calls for financing tied to environmental and social safeguards but provides little guidance on how to secure these funds or ensure they are directed toward Indigenous communities and their organizations.

Without specific and robust mechanisms to hold corporations accountable for human rights violations and environmental degradation, it is highly likely these recommendations will fail to protect those most affected by mineral extraction. Corporations often find ways to escape accountability, making it extremely difficult to secure justice for Indigenous Peoples, as well as local communities and others whose rights are violated. For example, this year marks the second anniversary of the Jagersfontein tailings dam failure in Free State, South Africa (September 2022). Many people from Charlesville and Skoti remain displaced, with little to no compensation for their basic losses. The devastation, which flooded homes and destroyed livelihoods, is still visible, as efforts to reclaim waterways and farmland continue at a painfully slow pace. Even more tragic is the 2015 Mariana disaster, where 43.7 million cubic meters of mine tailings were released into the Doce River—the sacred Watu of the Krenak Peoples—which remains in a state of "coma." Similarly, the 2019 Brumadinho collapse took 272 lives, flattened entire villages, and left survivors still struggling for justice. Year after year, these companies evade responsibility, leaving devastated communities to suffer while they continue to profit.

Photo by Brazil Senate.

The United Nations Secretary-General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals emphasizes crucial aspects of equity and justice, particularly in relation to Indigenous rights. It strongly advocates for Indigenous Peoples’ Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), which is commendable, but for the report to not become a mirage in the desert, a beautiful thing on paper, we need more than just lofty recommendations. We need more courageous actors, strong legal and political action, concrete commitments, and justice being served to change the course of the colonial legacies of States and industries, which our communities still face.

Top image: The expression Siren song, almost a cliche nowadays, comes from Greek mythology. Sirens were creatures that looked like beautiful women on top but had bird-like bodies. They sang such enchanting and irresistible songs that sailors would be drawn toward them, often leading them into danger or even causing their ships to crash.