By Phoebe Farris (Powhatan-Pamunkey)

This year’s annual Pocahontas Reframed Film Festival took place November 22-24 at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture and the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Many of the films directly or indirectly referenced the significance of 2024 being the 100-year anniversary of two significant events in American history: the Indian Citizenship Act and Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was an act of the U.S. Congress that officially bestowed—or imposed—U.S. citizenship on the Indigenous Peoples in the U.S. Although the 14th Amendment to the Constitution defines as citizens anyone born in the United States, Native Americans had previously been excluded from this proviso.

In Virginia, the Racial Integrity Act, also passed in 1924, prohibited interracial marriage and began a series of discriminatory practices and racial designations within the state. From 1912-1946, Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics required that all infants have birth certificates classifying them as white, ‘colored,’ or American Indian. Mattaponi and Pamunkey infants were the only babies legally allowed to be identified as American Indian because they were born on the reservation or if born in a hospital where their parents lived on the two reservations. After 1924, the Bureau became even stricter, fining and/or imprisoning midwives who wrote American Indian on birth certificates of babies not born on the state’s two recognized reservations. This paper genocide included changing the legal race of all adult Indians living off the reservation to ‘colored,’ regardless of their Tribal identity.

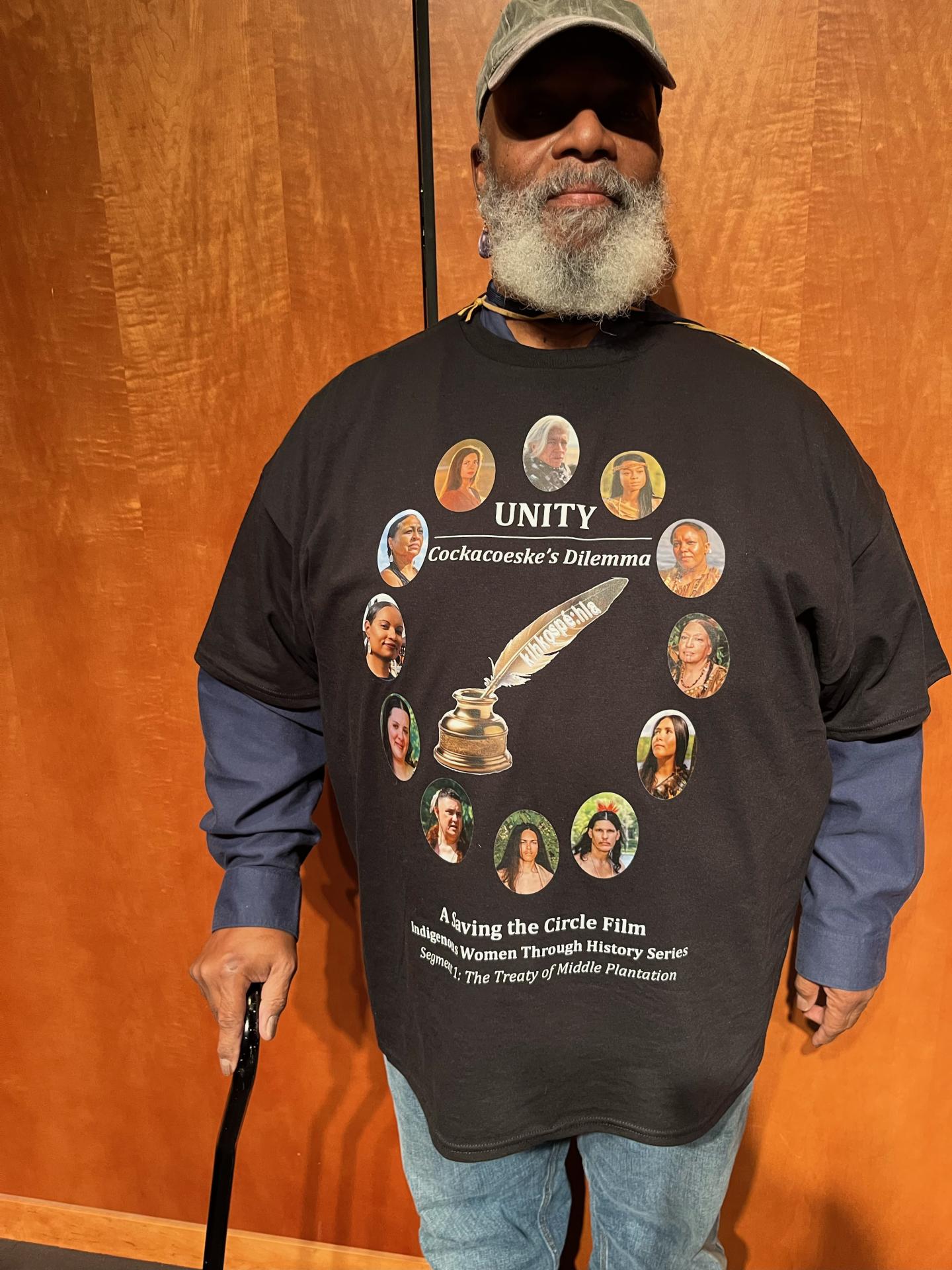

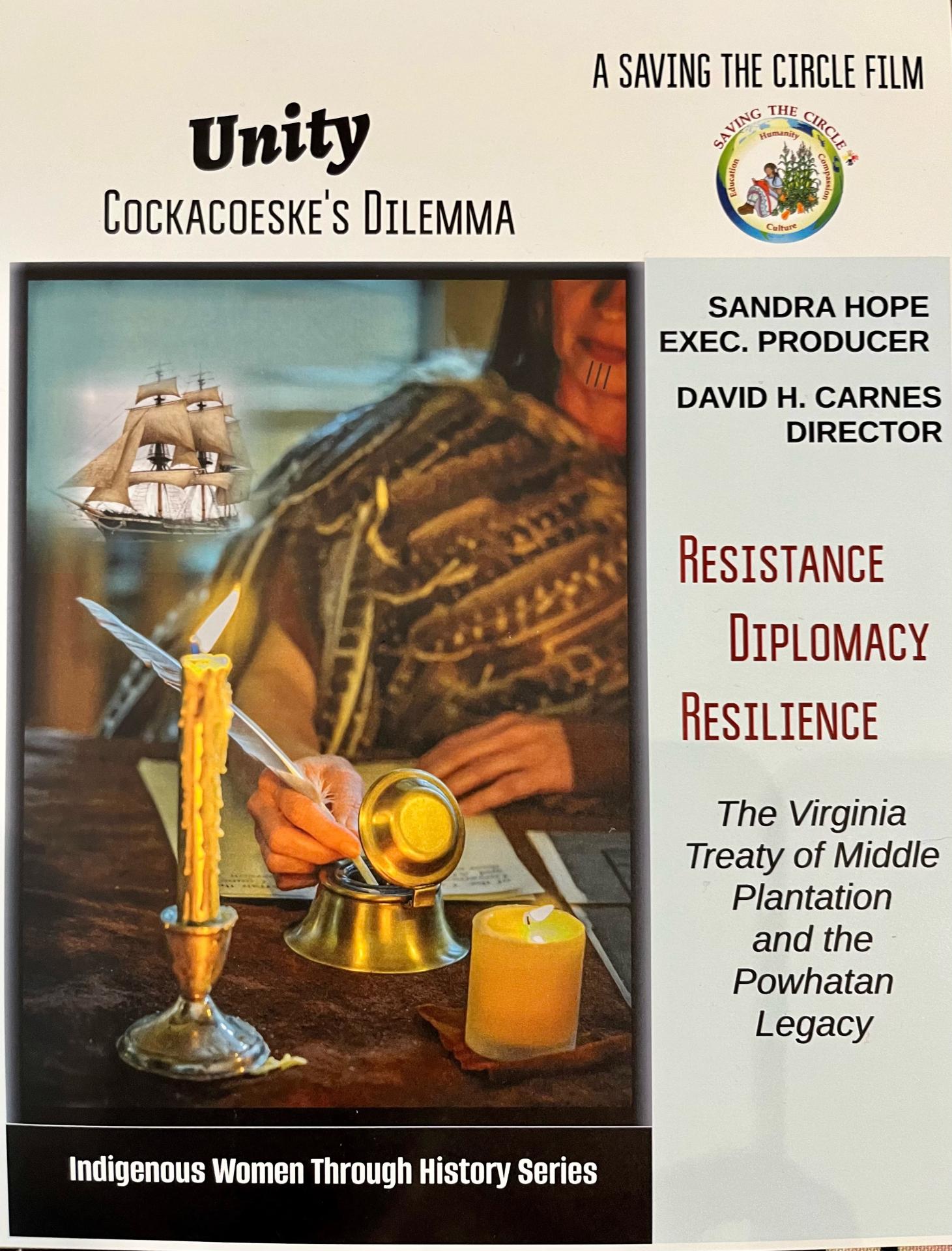

Sandra Hope (Haliwa Saponi) David H. Carnes (Echota Cherokee) (below), executive producers of “Unity, Cockacoeske’s Dilemma.”

Some of the films and presentations that reflected these issues were “Reclaiming Identity” (2024), a short trailer that “offers a glimpse into the stories, struggles, and resilience of Virginia’s Native communities as we mark 100 years since 1924.” “Who Can Identify as Native American” (2024) deals with the controversial topic of “Pretendians” and whether being Native is based on blood, initiation, or just a self-defined claim. “Unity, Cockacoeske’s Dilemma” (2024) explores contemporary descendants of the Powhatan Confederacy, sharing their stories of identity and reflecting on the history of the historical ‘Queen’ of Pamunkey and signatory of the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation. Also featured was “1666: A Novel,” featuring a discussion with author Lora Chilton about the survival story of the Patawomeck Tribe of Virginia, who, in 1666, suffered a massacre resulting in the deaths of the majority of the men and the forced abduction/enslavement of the Tribe’s women to Barbados.

The festival included many Canadian feature films, documentaries, and shorts, including “The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open” (2019); “NIGIQTUQ (The South Wind)” (2023); “Ajjigiingiluktaaqtugut: We Are All Different” (2021), “Rosie”(2023); “Coming Home (Wanna Icipus Kupi)” (2019); “Little Bird” (2023); and “Stellar” (2022).

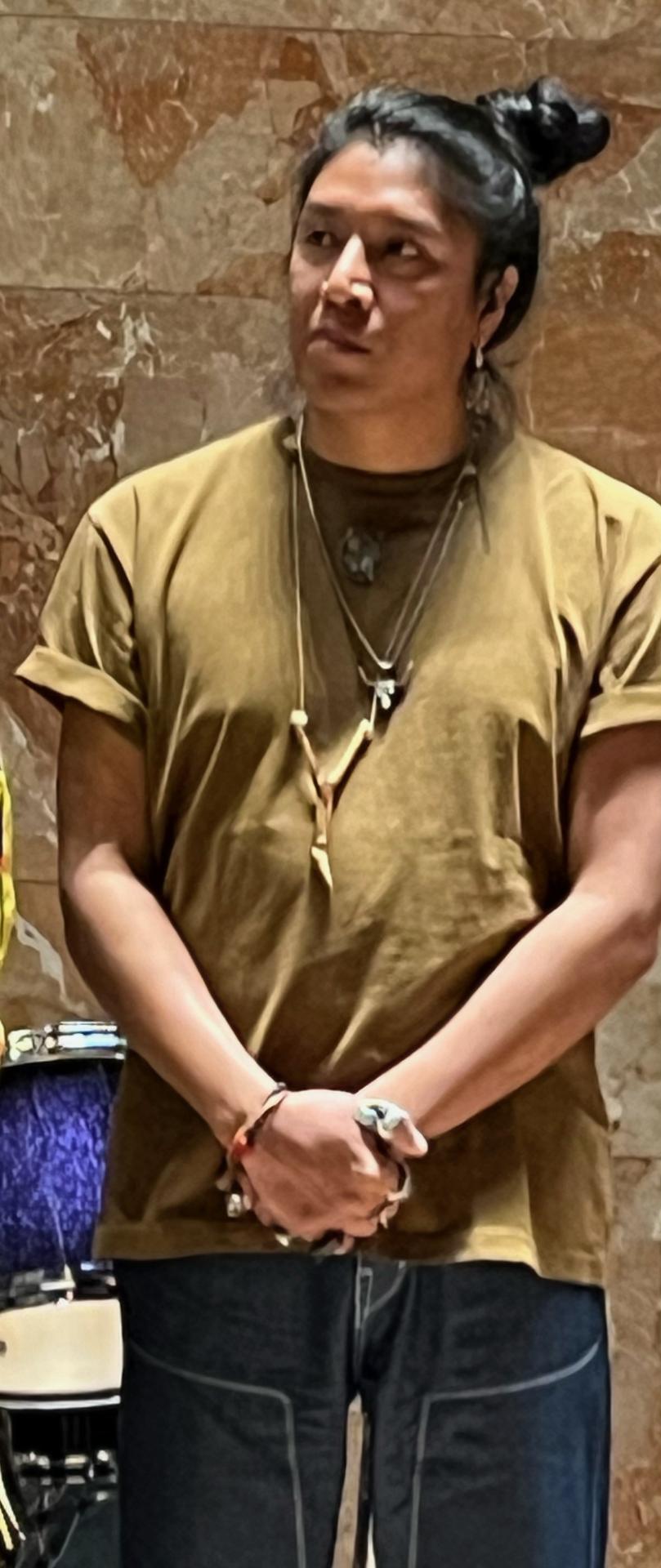

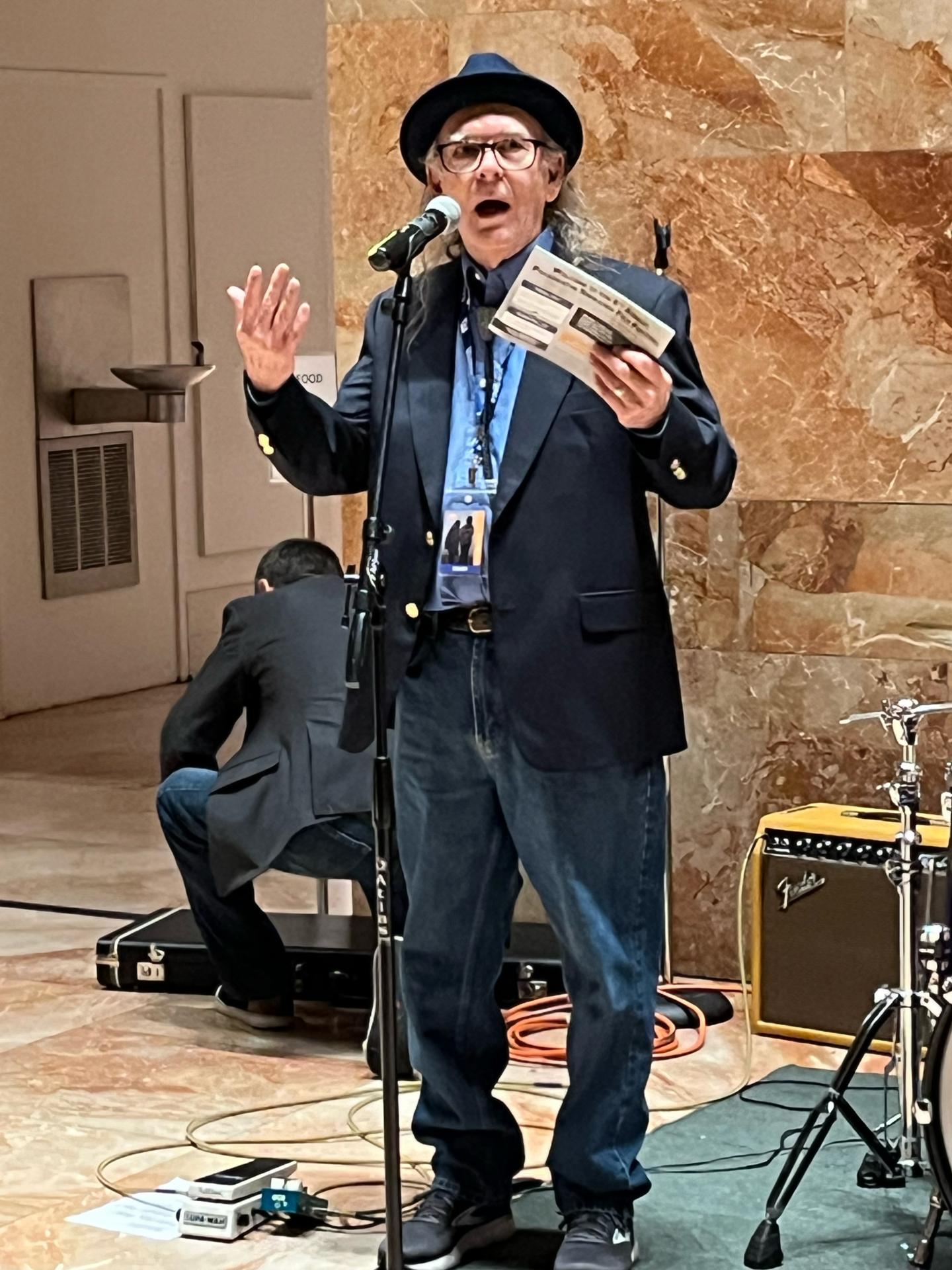

Filmmaker Federico Cuatlacuatl (Indigenous Mexican).

Other international films focused on Mexican and South American Indigenous Peoples. “Mukí Sopalírili Aligué Gawíchi Nirúgame-Piano (The Woman of Stars and Mountains)” (2023) is a documentary about Rita Patiño, a Tarahumara woman who migrated to Kansas and was involuntarily confined to a psychiatric hospital for 12 years, mainly due to language barriers. “Hatarimuy (Rise Up)” (2023), set in Peru and filmed in Quechua and Spanish with English subtitles, focuses on a young man injured in a protest march as he questions his true identity as an Indigenous Quechua versus the government’s preference to identify his Peoples as Mestizo, tracking the process of his internal decolonization.

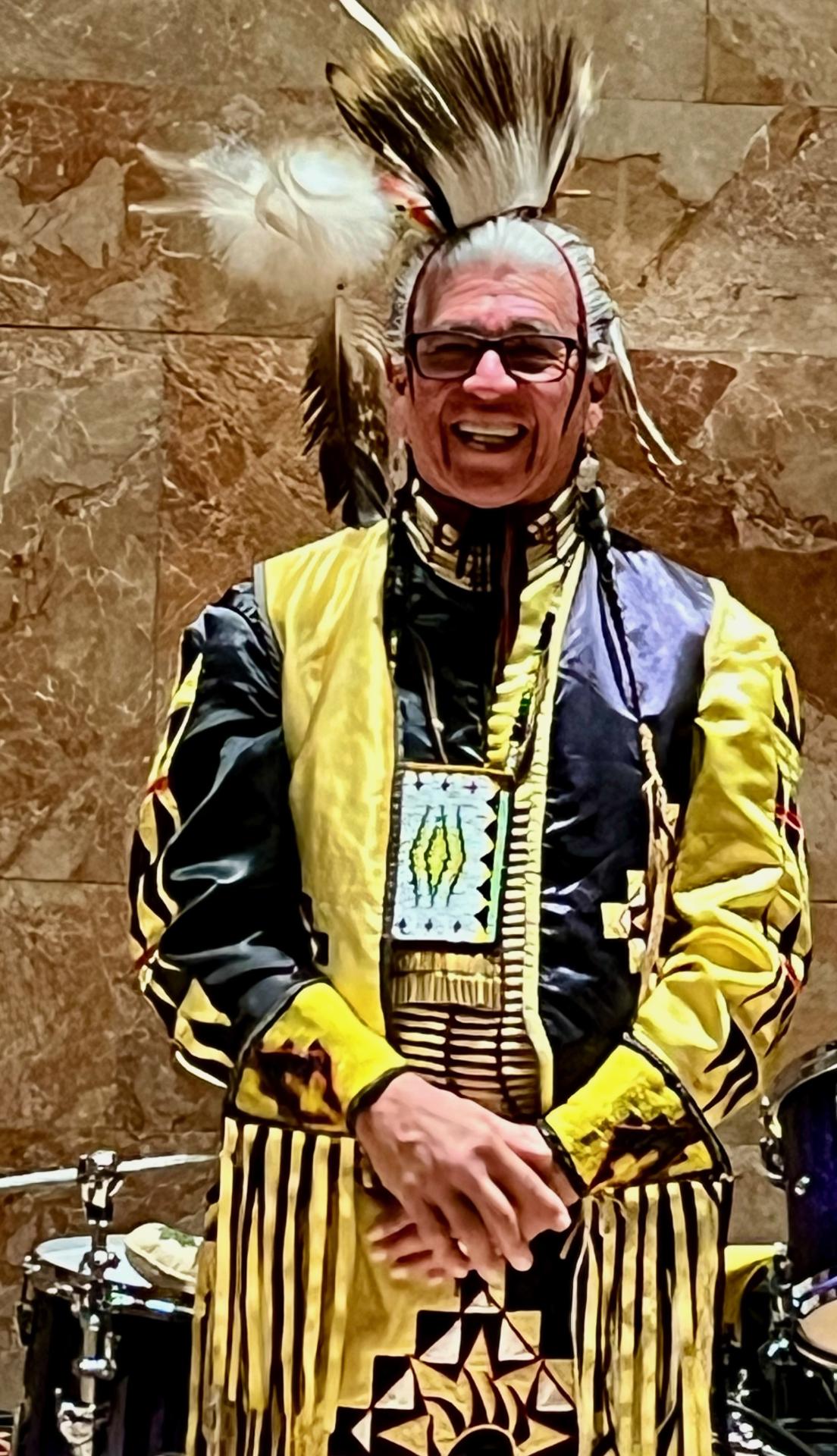

For the first time in its eight-year run, this year’s film festival also included a Family Day Powwow and a Nashville-style Native musicians’ round featuring Koli Kohler (Hupa/Yurok/Karuk), Darren Thompson (Ojibwe), and Suni Sonqo Vizcarra Wood (Quechua), in addition to the annual Tsenacommacah Eastern Indian Market.

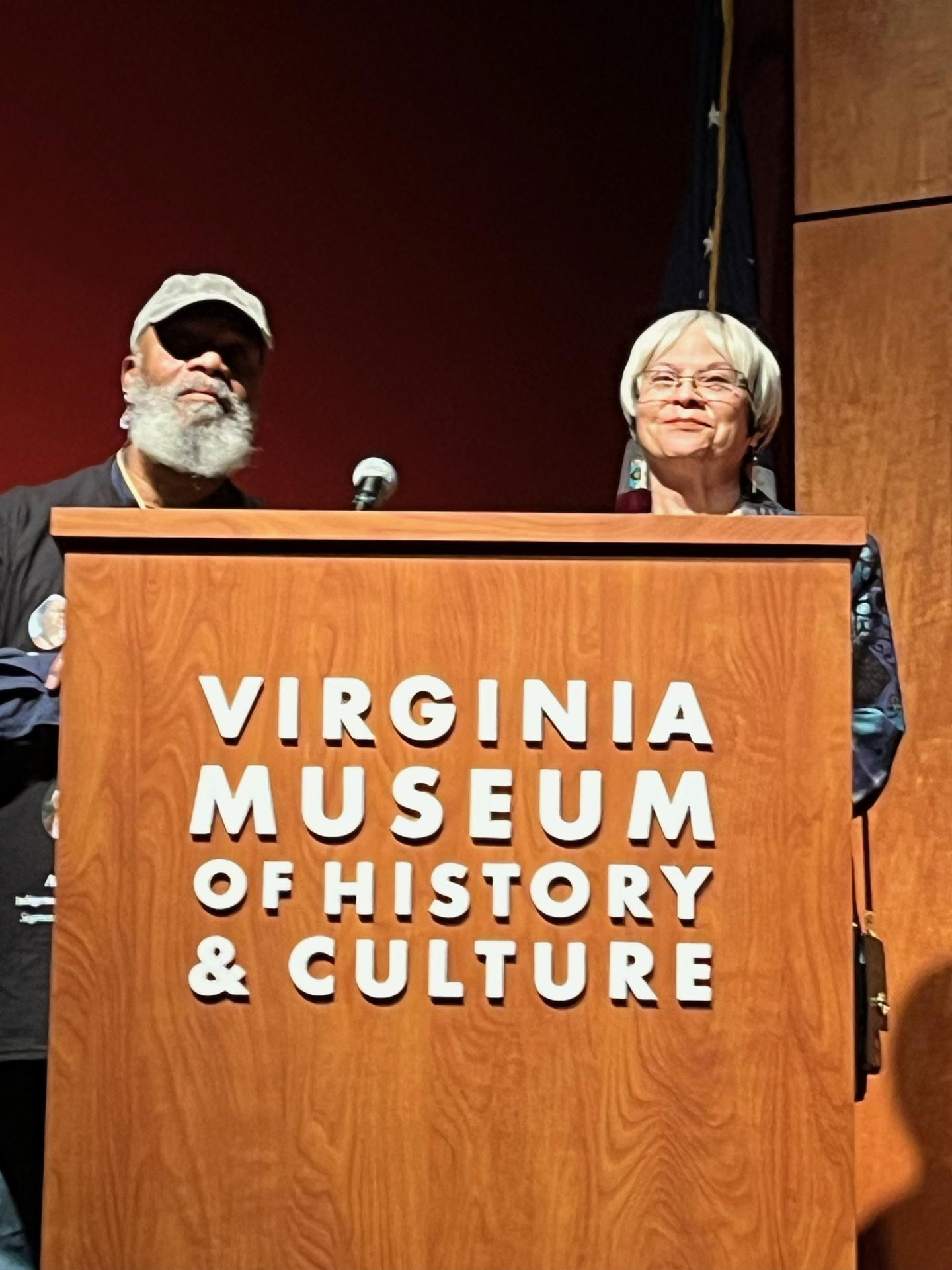

Board of Directors members Sam Bearpaw (Apache) and Bradby Brown (Pamunkey), below.

“Coming Home” and “Little Bird”

“Coming Home,” produced by Rezolution Pictures and directed by Erica Daniels, is a documentary about “Little Bird,” a 2023 made-for-television miniseries that dramatizes the impact of Canada’s ‘1960s scoops,’ a policy that involved the government “scooping” up Indigenous children and placing them with non-Indian foster families or for adoption. Indigenous parents or close relatives had no custodial rights and didn’t know where their children were placed, causing decades of trauma for the children and their biological families. Daniels narrates with historical information about the ‘60s scoops and their impact on the main character of the series, which is based on the true story of a young Native girl who was adopted by a Jewish Canadian family (that renamed her and converted her to Judaism) and her adult quest to locate her biological family. The lead actor’s own grandfather was a “scooped” child, which she credits for giving her better insight into portraying the adult Indigenous/Jewish character. One of the male actors in the series who is featured in the documentary is of Inuit/Senegalese/European descent, and was also adopted as a child. In the film, he says that his mom gave him an Indian name and his adoptive mom gave him a slave name. Filmed in Saskatchewan, the film crew chose Indigenous communities for locations, asked permission to film there, and included Sioux Valley community members as background actors.

“Little Bird” also had an authenticity consultant who researched Indian houses from the 1960s, which usually had no indoor plumbing or electricity—conditions that were considered grounds for removing children from families; the episodes that highlighted Little Bird’s Indian house were based on a real house from family photos. A Métis producer from the Broken Head Ojibwe Nation posed the question, ”What is a nation without its children?” And in labeling the scoops as cultural genocide and systemic racism, crew members stressed the importance of having a predominantly Indigenous crew and film set for narrative sovereignty. Several crew members said they were making stories like this for their People, to help remind them of their worth.

In 2020, Canada’s parliament passed legislation that made these forced adoptions illegal, and because of Bill C-92, Indigenous families now have legally protected jurisdiction over their children. Keris Hope Hill portrays Little Bird in the series, which streamed on Hulu and PBS. Her mother was on set during some of the heart wrenching dramatic scenes, and Indigenous crew members supported the actors in these difficult roles, understanding the pain they may have been feeling based on their own lives and the lives of some of their relatives who were victims of the scoops.

Board member Chief Lynette Allston (Nottoway) and Chief Gray (Pamunkey).

“Unity - Cockacoeske’s Dilemma”

“Unity - Cockacoeske’s Dilemma” is executive produced, directed, and written by David H. Carnes (Echota Cherokee) and Sandra Richardson-Hope with support from the cast. The short film is the first in the Indigenous Women Through History Series produced by Indigenous Unity. In the film, a multigenerational gathering of contemporary descendants of Tsenacommacah “explore shared Powhatan Confederacy heritage [where] they will awaken the spirit of an ancestor and begin their journey through the history of Chief Cockacoeske, the renowned ‘Queen’ of Pamunkey and signatory of the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation.”

We journey with the Chief/Queen as she travels through time, meeting a young Pocahontas/Matoaka (the daughter of Chief Powhatan), and at various other stages of her life, as a young adult and as an older woman signing the treaty. We also meet a young male warrior hunting for bison, young Pamunkey women doing traditional chores, and contemporary Native Americans discussing their various Tribal heritages and the racism of Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act, including its ongoing impact on their identity and their hopes for a future of more unity among Indigenous Peoples.

Chief Cockacoeske was a descendant of Opechancanough, brother of paramount Chief Powhatan. After the death of Cockacoeske’s husband, Topotomy, who served as Pamunkey Chief from 1649-1656, she became the chief, and was called Queen by European colonizers. A few months prior to Bacon’s Rebellion, Nathaniel Bacon and his rebels attacked the Pamunkey, taking captives and killing many members of the Tribe. In February 1677, the Chief/Queen asked the General Assembly to release the captives and restore her confiscated land. She signed the Treaty of Middle Plantation on May 29,1677, and regained authority over several Tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy.

With a few exceptions, most of the clothing, landscape, and traditional architecture in the film is historically accurate. However, there are some anachronisms. For example, Indigenous Pamunkey women and those of similar Tribes had face and body tattoos, which were not replicated on the actors. Pamunkey women also did not wear their hair long and flowing down their shoulders and backs as portrayed by Pocahontas and Cockacoeske in the film; based on drawings by John White and other period artists, the women appear to have worn their hair in loose buns tied behind their necks with short, fringed bangs covering their foreheads. The one-shoulder dresses worn by the women outdoors are historically accurate, as are the feathers and pearl cape worn by Cockacoeske when she was signing the treaty. But the dress worn by the younger Cockacoeske resembles contemporary Indian women’s fashion created by 20th and 21st century Native designers.

Fictionalized portrayals of historical figures help educate audiences about Indigenous cultures in an entertaining format, but it is still important to maintain historical accuracy regarding material culture. Despite these minor flaws, “Unity - Cockacoeske’s Dilemma” was enthusiastically received by the audience with much emotion. And many, including this reviewer, look forward to future productions from Saving the Circle’s Indigenous Women Through History series.

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

“Ajjgiingiluktaatugut (We Are All Different)” is an animated documentary that asks the question, “What does it mean to be Inuk?” It is an exploration of Inuit identity across the globe, not just limited to “remote snowy landscapes.” Inuit filmmaker Lindsay McIntyre also asks, “What does it mean to be human?”, a question relevant in all the films, especially considering that the English translation for many Indigenous Tribal names is “the human beings” or “the people.”

David Barnes and Sandra Hope.

During the post-screening presentation, Sandra Hope and David Barnes also reflected on what it means to be Indigenous and/or a member of a specific Tribe, and how these identifiers can and should be more expansive. Hope commented, ”We want unity and would love to see less focus on having a paper card to prove you are an Indigenous person.” Speaking about her film crew for “Unity: Cockacoeske’s Dilemma,” Hope said, “Everyone knows the road we walk. We walk it in generosity and kindness. We are all blended and our crew was very united and we all worked together.” Barnes stressed “accountability for the wrongs that have been done” to Indigenous Peoples and the “responsibility to build bridges that need to be built.”

The overlapping themes of belonging (or not), identity, displacement, enslavement, dispossession, land acknowledgement and land back, blood quantum, race, citizenship, and immigration were integral to both the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 and the 1924 Virginia Racial Integrity Act. These issues are still relevant today, 100 years later.

--Phoebe Mills Farris, Ph.D. (Powhatan-Pamunkey) is a Purdue University Professor emerita, photographer, and freelance art critic.