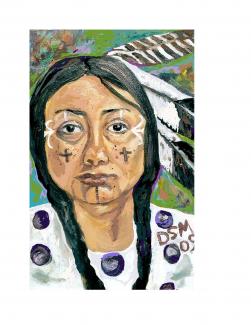

Deborah Spears Moorehead, an artist from the Seaconke, Pokanoket, Wampanoag, Narragansett, Pequot, Mohawk, and Nipmuc Tribal Nations in New England, has been drawing since she can remember. “The Creator chose me to have the talent to be an artist. I started drawing when I was old enough to pick up a pencil,” she says. There is artistic talent on both sides of her family, and Moorehead says her own pull towards artistic forms of expression follows a familial line. She recalls watching her mother create “beautiful renderings of people that she knew,” and drawing during family visits to her grandparents. “My grandmother would just give me a paper and pencil and tell me to draw anything that was in front of me.”

During her middle school years, an experience at a lifelong friend’s house helped her discover her current medium: oil paint. “[My friend’s] mother gave us a canvas and paint, oil paint, and I painted a raccoon. I fell in love with oil paint from that day on,” she recalls. While oil paint continues to be her medium of choice, Moorehead explains that she usually begins with colored pencils. “I like to use colored pencils to do a study of what I’m going to paint so that I can work out any problems with color before I get into the oil painting.” After receiving her bachelor’s degree from the Swain School of Design, Moorehead earned a Master of Arts in Traditional Cultural Sustainability. Today, she runs her business, the Painted Arrow Studio-Talking Water Productions, in Richmond, Rhode Island. Moorehead not only designs, produces, and sells her art, music, and jewelry; she also organizes and coordinates art shows and musical performances, and teaches private art lessons to children and adults alike.

Moorehead’s own artwork focuses on the Eastern Woodland Native American community. She recalls being a young student in school, learning from curricula that taught her that Eastern Native Woodland peoples were extinct. “That made it really difficult for me to develop an identity, when all society was telling me that I didn’t exist,” she says. The experience recurred when Moorehead attended college in Massachusetts: “The professors were teaching the art of European people,” and “[I] constantly yearned for a Native American teacher who would teach the history of the Native Americans and their art.”

These experiences led Moorehead to a decision that continues to shape her work. “When I was old enough to assert my own way of identity… I decided that as an artist, I’m going to paint my people and document that we’re here. And if we’re here now, we had to have been here in the past. If we’re here now, we have to be here in the future.” Her goal is to create pieces that collectively validate all forms of Eastern Woodland Native identity, past, present,and future. She documents through what she describes as “pinpointing the obscurity” of the people.

“It’s saying, our history was obscured for certain reasons, but it can’t be obscured if I say and paint, ‘here we are, right now. We’re here and have always been here!’” In doing so, Moorehead’s work retells an accurate history, one that does not relegate Native people to the margins, but rather one that connects Native peoples within and between communities and across borders. Her pieces have been displayed in schools, universities, museums, libraries, and a variety of other public venues across the country, including the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, Brown University, Harvard University, The Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), The Rhode Island School of Design, and The Mohegan Tribal Nation. Her work has also been displayed internationally, for example, in the International Gallery of Bolivia.

Both domestically and internationally, Moorehead hopes that her work communicates to all Indigenous people “that we all have a lot of work to do.” Her intent, to link Indigenous Peoples together on a global level, centers on survival and cultural sustainability. “Our survival is very critical. We’re only one percent of the population, so it’s very critical that we protect the traditions, the culture, the people. A lot of Indigenous people are facing the same kind of issues that we’re facing,” she says.

Moorehead’s deep-rooted beliefs about her art and teaching have led to a variety of fascinating and rewarding experiences. In 2006 she was awarded the Youth Mural Project Grant, through which she collaborated with the Tomaquag Indian Museum and students from the Nuweetooun School to create a mural entitled, “Nuneechun NuPeesh Kanashunun,” or “Our Children, Our Future.” The mural project emphasized the importance of being witnesses of colonization and pushing back against the effects of that colonization. Moorehead says that the best part of the experience was working with the children, continuing in the tradition of her ancestors.

More recently, Moorehead furthered her community outreach by working as the curator of the first annual state Native American art exhibit at the Rhode Island State Council of the Arts. The exhibit highlighted the work of Eastern Woodland Native artists, who, she says, as underserved artists, are often “intimidated to be in venues that they’re not familiar with.” The mission of the exhibit was to work towards artistic cultural democracy, the idea “that all people—every culture, every nationality, every ethnicity, everyone—should be equally able to participate in the arts.”

For Moorehead, this form of cultural democracy is connected not just to the arts, but to sovereignty and cultural sustainability as a whole. “One of the most prominent issues for Native Americans today is our sovereignty,” she says. “We are sovereign nations; we need our land to be able to sustain our culture; we need the environment to be protected. There need to be more cultural policies that can assist Native people with being advocates for themselves. We need free, prior, and informed consent when decisions are being made that affect our environment; we need advocates that assist in all ways for readiness, as representatives of our nations.”

As for her own role in this process, Moorehead says, “I see my work as a way of communicating an injustice to Indigenous people, and I find that my masters degree has given my paintings more to say. My daughter said at one point, ‘Mom, this degree has given your paintings a voice,’ and that voice is one that speaks out for social justice. I believe that art has its

own language. And like they say, a picture speaks a thousand words.” Moorehead works not only to bring out that voice from within herself, but from others as well. “As a teacher I can assist anyone to express whatever they want to communicate. It’s hard to paint something that you’re not feeling, and it’s hard to not feel when you’re painting.” Advocacy for and by Native peoples, accurate and thoughtful documentation of Native life, and the creation of connections across Native boundaries and cultural lines: as Moorehead illustrates, the universality of art opens up an ideal space for taking these crucial steps toward cultural democracy. “It doesn’t matter what community you come from,” she says. “Art has its own language, and we all speak that same language.”

—Hannah Ellman is a former Cultural Survival intern.