Human rights are measured through United Nations human rights conventions and covenants. Regular reviews monitor how states are realizing the rights recognized in the treaties. Civil society can influence international institutions by participating in every phase of the review process. Involvement of Indigenous Peoples is imperative to seek justice through every review, contributing to global standard setting. In this series we aim to break down the core treaties.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is an international human rights treaty pertaining to women to guarantee gender justice. Enacted on September 3, 1981, it created a comprehensive legal standard codifying the rights of women in public international law and a committee to regularly review the process on elimination of discrimination against women. The revolutionary spirit of CEDAW is its applicability in private and public realms of society, as it focuses on all forms of discrimination against women around the world.

Composition and Consideration of Country Reports

A 23-member committee of experts reviews States as guarantors of the rights in CEDAW’s upholding principles of universality, indivisibility, inalienability, and interdependence of all rights. Equality and non-discrimination against women is central in all deliberations and actions of the committee. Experts review reports prepared by States and strongly encourage consultation with civil society, specifically women’s associations. When a country ratifies the Convention, it must submit an initial report within one year. Periodic reviews are subsequently due every four years.

The committee meets three times a year for sessions of at least three weeks to review State reports, host dialogues on imminent issues facing women fighting for fundamental freedoms, and draft concluding recommendations based on these interactive dialogues. On the opening day of the session, civil society can speak directly to committee members. During the lunch session the day prior to review of one’s State, there is also an opportunity for civil society to discuss the main issues that deserve attention during the interactive dialogue with the State. It is important for individuals to be succinct in raising specific rights to be respected, protected, and fulfilled. This is to ensure experts have significant time for questions and comments so they will be prepared to fully engage on specific situations in each State.

Each review is five hours long, with States opening the process by sharing steps taken to realize women’s rights. A rapporteur assigned by CEDAW members begins the interactive dialogue with questions and comments regarding the report, responses to the list of issues, and specific situations that require immediate action. The remaining members ask questions and make comments in the order of the articles of the Convention to the state. Before each article is discussed, the country responds to the experts’ points, and in some cases there is followup by experts to fully understand the situation of women’s rights in the State. At the conclusion of the review, the rapporteur and the State each make closing statements. Before the session concludes, recommendations are issued at a press conference in Geneva that are to be implemented before the next review. Prior to departing Geneva, there is a working group meeting of CEDAW to prepare for the next session.

Optional Protocol to Address Rights Violations

One tool to tackle human rights violations is an Optional Protocol, drafted by the UN Commission on the Status of Women in 1992, adopted on October 6, 1999, and enacted on December 10, 2000. Under the protocol, the committee considers petitions claiming violations of the Convention. An appointed five-member working group on communications reviews all submissions. States must ratify the protocol in order for women to be able to bring complaints to the committee for consideration.

There are two mechanisms included in the Optional Protocol. The common practice is the communication procedure, which allows individuals and groups to file complaints regarding violations of rights enshrined in the Convention directly to the committee. The complaint is forwarded to the State in question with a request for a written response to the rights violations. There is no time limit regarding claims considered. The submission must detail the violation of CEDAW and ask the committee to provide advice in terms of policies and practices to address the violation. The State has six months to respond. Additional information can be sought regarding the State’s alleged violation from UN specialized agencies as well as civil society.

The communication details the specific violation of CEDAW and demonstrates that domestic remedies available were taken with no redress provided. The communication can also prove whether domestic measures are ineffective, unavailable, or unreasonably prolonged, and could lead to even more grave situations and harassment for the complainant in the country. Once the communication is received and deemed admissible, the case merits are considered. The committee can request interim measures due to the potential for harm or irreparable damage to the complainant’s life or situation. The process is considered confidential while being considered; however, the committee can chose to make it public. The committee issues its finding and concluding recommendations to the State. At the subsequent regular State review of CEDAW, there will be a review of the implementation of the recommendations.

The second mechanism is the inquiry procedure. Under this procedure, the CEDAW committee can conduct broader inquiries into systematic violations of women’s rights. A formal visit to a State being reviewed is a potential part of the process with an option for a hearing to be held. However, consent of the country is a prerequisite. Under the protocol, States can ratify the Convention but refuse to allow the committee to conduct an official visit.

The review of all information gathered and reviewed by the committee results in an adoption of the findings and citation of whether a violation has officially occurred. The committee also identifies specific actions by the State to remedy if it finds a violation of women’s fundamental freedoms has occurred. The committee’s findings are published and the State has six months to respond. Remedies that exist under the optional protocol include the review or repeal of existing offending laws, adoption of specific measures to prevent and remedy future violations of CEDAW articles, and payment of monetary damages.

General Recommendations

General recommendations are essential extensions of the Convention. Administered under Article 21, they address any issue affecting women that is deemed to receive more attention. Recommendations may elaborate on articles in the Convention and provide guidance to governments on interpretation of enshrined rights, or outline actions to be addressed for compliance with the Convention.

Participation in the creation of a general recommendation is encouraged in a three-stage process. The committee conducts an open dialogue among experts, NGOs and interested individuals, and UN specialized agencies. The open dialogue is based on prepared position papers and conversations developed during the interactive exchange of the open dialogue. A CEDAW member is then tasked with drafting the general recommendation to be discussed at a subsequent session where the revised draft will be adopted. Over 30 general recommendations have been issued so far, along with a general recommendation jointly drafted with the Committee on the Rights of the Child. There is currently a call for a general recommendation on Indigenous women to illustrate the intersection of rights regarding gender and indigeneity.

CEDAW Cycle of Consideration

The UN human rights treaty body process has five phases: preparation, interaction, consideration, adoption, and implementation. The first and final phases begin in one’s community and country, where human rights matters most—in Indigenous Peoples’ daily lives. The middle phases are centered around Geneva and the campaign with the committee experts. For each phase it is essential to coordinate a creative campaign in all three levels of grassroots community, country, and global civil society.

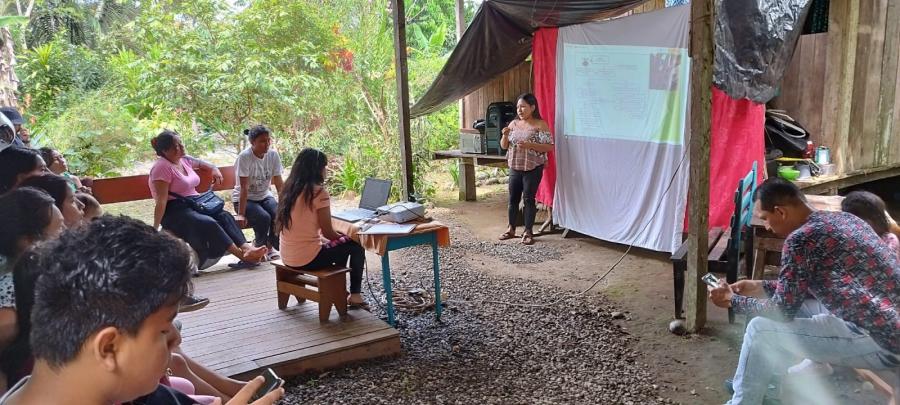

The preparation phase is geared toward educating people to participate effectively and prioritizing specific rights to raise at the UN human rights treaty body. The heart of the action is examining the record of rights and starting a creative campaign to realize these rights. The interaction phase consists of initiating participation with the CEDAW committee members and ensuring that the interactive dialogue is rooted in reality. This phase prepares the committee to be able to better discuss the facts to change conditions. It is also where people interact with their States to partner, if possible, and pressure when necessary for the realization of rights. The building of relationships is the basis for the interaction phase.

The consideration phase revolves around the rights raised in the review of the State. The motivation of the human rights mechanisms review should be generated from the grassroots level and support the demands for dignity at the global level. This phase should empower people coordinating the campaign, realizing their ability to advocate and create accountability of their government utilizing the UN human rights treaty body institutions.

The adoption phase is where general recommendations are issued to the government to realize rights in a state. It is the result of the entire process, from shadow reports to examination of States, including briefings by civil society with human rights treaty experts. The implementation phase closes the cycle, ensuring the process results in rights realization for people. Impacted individuals and concerned communities should be at the forefront in demanding their governments guarantee fundamental freedoms reflected in the concluding recommendations.

—Joshua Cooper is a professor at the University of Hawai’i, West Oahu, Kapolei and director of the Hawai’i Institute for Human Rights.