Ladakh is a high-altitude desert in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. Covering an area of 40,000 square miles, it supports a population of only about 120,00, the majority of whom make their living through subsistence agriculture. The climate is extreme: rainfall averages less than four inches per year and winter temperatures can fall as low as - 40°F. In 1974 the region was opened to international tourism, and the old culture faced a rapid invasion of the modern world. Tourist arrivals grew rapidly from a few hundred in the initial years to around 15,000 by the mid-1980s. Foreign tourist arrivals have stabilized at about this level.

The last 15 years have seen a vigorous program of development in Ladakh, which has brought changes in education, health care, agriculture, energy, and transportation.

Tourism is concentrated in the predominantly Buddhist settlements of the Indus Valley, of which the ancient capital and trading center of Leh (population 8,000) is the hub. Many areas of Ladakh are still off limits to foreign visitors due to their proximity to the Chinese and Pakistani borders. A large part of southern Ladakh is accessible only by foot.

Ladakh, sometimes referred to as Little Tibet, is popular with tourists because it is home to one of the purest remaining examples of Tibetan Buddhist culture. Visitors come to see a preindustrial culture, tour the Buddhist monasteries, and take in the dramatic mountain vistas.

Tourism's Impact: Paying the Price

Tourism, a major contributor to Ladakh's cash economy, has brought clear economic benefits to the minority involved in this trade. The tourism economy is centered around Leh, and very little of the economic benefit of tourism accrues to the more than 90 percent of Ladakhis who live outside of this area. Within Leh the handful of Ladakhis who own large hotels benefit disproportionately. Much of the money spent in Leh goes to tour operators and merchants who come to Ladakh just for the tourist season. Those who do live outside of Leh benefit somewhat from trekkers. They frequently rent out their pack animals and occasionally lodge trekkers not traveling with prearranged tour groups (Pitsch 1985).

The problem goes beyond an uneven distribution of the benefits, however. Those not participating can become economically worse off simply by continuing to live as they always have. The reciprocal relations of mutual aid are broken down by the extension of the monetary economy, and tourists' demands for scarce resources drive up the prices of local goods.

For example, in the past villagers commonly shared pack animals in informal exchange relations. Now, during the tourist season, animals are no longer available to a neighbor in need: they are frequently off in the hills carrying tourists' luggage. Nor can a villager afford to hire the extra animals he might need to carry his loads from the high pasture. Similarly, villagers have begun selling traditional building materials in Leh, where a building boom induced by tourism supports far higher prices than what fellow villagers might offer. Where once economic surplus stayed within the villages, it is now absorbed into the larger market. As a result inequality within the villages is growing.

Tourism has had a direct negative impact on Ladakh's environment. Many tourist facilities that attempt to maintain Western standards end up making demands on scarce water resources that are far beyond what the community usually requires. Communal water sources have been tapped for the exclusive benefit of particular hotels, and during dry periods hotels have brought in water by tank truck.

Until recently Ladakh had no waste problems; everything could be cycled back to the land. The large volume of wastes produced in the modern sector is polluting land and water and has increased the incidence of disease sharply. For example, many hotels have faultily designed water-based sewage systems that contaminate local streams. The construction boom in Leh has not kept up with the rapid influx of people, forcing many temporary residents, drawn by the tourist economy, to live in rented rooms without access to water or basic sanitation facilities.

Tourists also demand energy services above what local residents require. Cooling, heating, lighting, and transportation needs have been provided primarily by fossil fuels trucked over the Himalayas, adding diesel fumes, coal smoke, and spent oil to the list of Ladakh's environmental woes. In the mountains and villages away from the roads, trekkers use already scarce fuel and fodder resources, often without compensating the villagers. Tourism also brings indirect environmental problems as local residents begin to emulate the high consumption standards of tourists.

The social and cultural effects of tourism are more difficult to isolate from the effects of development programs and broader pressures for modernization. A look at some of the trends that have accompanied the growth of tourism can shed some light. The openness and friendliness that Ladakhis have traditionally shown to visitors has been eroded by the commercialization of their culture and their understandable resentment toward the invading crowds. Theft, virtually unknown in traditional Ladakhi society, is now a common complaint among urban tourists and trekkers alike, and children now plague visitors for handouts.

By observing foreign tourists on vacation, the Ladakhis - the young Ladakhis in particular - easily come to believe that all Westerners are rich, that they work very little, and that the West is a paradise of consumer goods. Young people begin to despise the thinking of their parents and rush to embrace whatever is seen as modern. They might fail to realize - or may realize too late - that "throwing off" traditions might lead to a real decline in well-being (Norberg-Hodge, in press).

The inequitable distribution of the receipts from tourism and the leakage of tourists' expenditures out of Ladakh has increased social tensions, especially between Buddhist Ladakhis and Muslims from the valley of Kashmir. During the summer of 1989, these tensions reached the boiling point. The Buddhist population of Ladakh began demonstrating in force for greater autonomy from the government of Jammu and Kashmir state, which is overwhelmingly Muslim. In the Buddhist sectors, where Muslims and Buddhists have coexisted peacefully for years (at least since silk route times), the unrest led to a polarization of the society along religious lines. Violence between protesters and the state police resulted in the deaths of four Ladakhis. Leh was placed under curfew for most of the summer, and tourist arrivals plummeted. The long-term effects of the unrest is unclear, although it appears that Ladakhi Buddhists may gain slightly more political autonomy. Whether one of the original sources of tension, the distribution of tourist receipts, will change is unclear.

Having completed a brief look at some of the problems associated with tourism, let us now examine some of the responses.

The Ladakh Ecological Development Group

The Ladakh Ecological Development Group (Ledeg), a Ladakhi nonprofit society registered in India, is seeking to promote sustainable development that harmonizes with and builds on traditional Ladakhi culture. Ledeg sponsors educational and cultural programs and demonstrates and disseminates appropriate technologies, especially renewable energy technologies. The group was organized in 1983 with the help of the Ladakh Project, a small international organization started by Swedish linguist Helena Norberg-Hodge in 1978.

Norberg-Hodge visited Ladakh in 1975 when the region was first opened to tourists. She became fluent in the local language and worked with Ladakhi scholars to compile the first Ladakhi dictionary. She founded the Ladakh Project to bring examples and information from around the world that would support development based on Ladakh's own resources and traditions and to counteract the belief among young Ladakhis that their culture was inferior. The Ladakh Project, now based in England, also works in Bhutan and in the industrialized countries, promoting development and environmental education. Ledeg continues to receive funds information from the Ladakh Project, but it has grown to include an all Ladakhi staff of about 50 and now receives support from the Indian government and from Scandinavian aid organizations (Ladakh Project 1988a).

The work of Ledeg and the Ladakh Project affects tourism both directly and indirectly. Ledeg distributes guidelines for responsible behavior for tourists in Ladakh. The Center for Ecological Development, Ledeg's headquarters in Leh, helps educate tourists on the larger context of development in Ladakh. The center's museum highlights the ecological and social balance of the traditional system.

Tourists help support the group's work financially and psychologically. Tourists' donations, along with profits from the center's restaurant and souvenir sales, help fund the educational and technical programs. Norberg-Hodge believes that the nonfinancial encouragement tourists give, too, is just as important as their donations.

Many tourists give up part of their vacations to pitch in and do what they can at the center. The mystique of the tourist is greatly reduced when both Westerner and Ladakhi are, for example, toiling side by side during Ledeg's annual Leh clean-up campaign. The center also provides a place where Ladakhis and tourists can meet and exchange ideas and experiences.

Ledeg and the Ladakh Project have started a program aimed at developing souvenirs based on traditional crafts and designs. The goal is to allow villagers to earn money without suffering the social and environmental costs involved with leaving the land. More locally produced souvenirs mean that a greater percentage of tourists expenditures go to villagers in Ladakh. The government and the Tibetan refugee camp also sponsor handicraft programs.

Ledge's educational work throughout Ladakh dispels the inaccurate images of the West that have accompanied tourists. Ledge's technical program attempts to show how tourists' high standards of comfort can be met with local resources. The Ledeg staff has built a solar hot water heating system for one of the luxury hotels that reportedly saved enough in coal costs to pay for itself in about two seasons. Ledeg has also designed hydraulic ram pumps that can lift water to rooftop tanks using only the energy of falling water; the ram pumps cost only a fraction o what electric pumps cost. Ledeg has shown that passive solar heating techniques, such as "trombe walls," can provide indoor comfort comparable to that of coal stoves, and that greenhouses can extend the growing season so that more of the vegetables served in restaurants can be supplied locally. Ledeg's restaurant is well known for cakes baked in its solar ovens (Ladakh Project 1988b).

Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh

In 1988 Sonam Wanchuk, a talented young engineering graduate, chose not to take a government job but to work instead for the preservation and promotion of Ladakhi culture by starting the Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (Secmol). The movement's goal is to improve education in Ladakh and preserve Ladahki culture. Tourism and the money it brings are central to both of these aims. Secmol sponsors nightly shows during the tourist season featuring traditional dances, songs, and music, with explanations in English. Some of Ladakh's leading musicians and performers have agreed to perform exclusively for Secmol. The 30- to 50-rupee (US $2 to $3.33) entrance fees pay the performers and support Secmol's educational work. The group occasionally organizes special cultural program with local scholars and students and facilitates meetings between tourists and Ladakhis. Secmol also runs excursions to popular tourist sites around the Indus Valley and sells postcards, cassettes, and local handicrafts to raise money.

The Association of Buddhist Monasteries, at Secmol's request, decided in 1988 that only guides knowledgeable in Ladakhi history and culture could accompany tourists to the monasteries; Secmol initiated short training courses for guides. Ledeg, the Ladakh Project, and Secmol are coordinating programs and cooperating on fundraising and long-term planning.

The founders of Secmol are very aware of the changes that tourism has brought to Ladakh. In its 1988 introductory brochure, they note that "No longer do you see naive Ladakhi men and women gracefully dressed in their `gonchas' and `peraks' wearing the smile of contentment and happiness. The younger generation seems to be giving up the elegant traditional lifestyle for some scrap Western values that the Westerns themselves abhor." The brochure goes on to say that Secmol is not against growth, progress, or tourism, but recognizes the need to "take carefully from the outside world the best of what it has, without losing our own values" (Secmol 1988).

Secmol intends to use the money collected from tourists to help improve education in Ladakh, particularly for students in government schools who are faced with the triple handicap of instruction in languages other than their native tongue, parents who have not gone through the same educational system, and indifferent teachers who share neither language nor culture with their students. Secmol's long-term goal is to get more Ladakhis to complete formal education and become teachers.

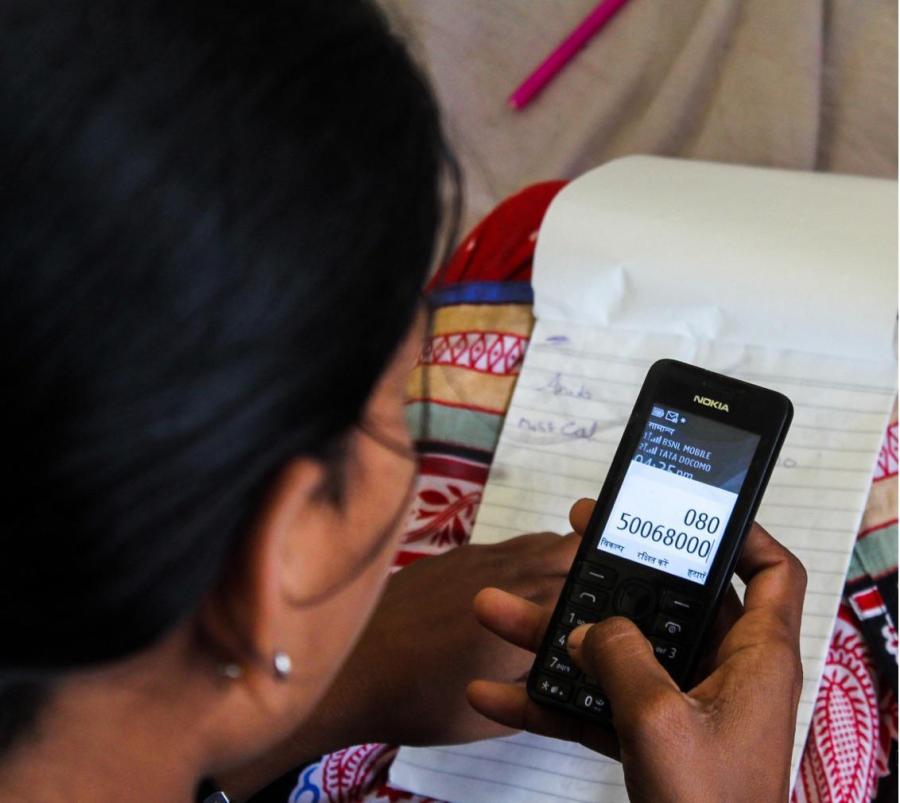

Secmol organizes older students to counsel and encourage younger ones as well as to provide academic tutoring. During winter vacation older students have taught courses in the Ladakhi language; future plans call for distributing audio or video cassettes of lectures by the best of these. Tourists are also asked to sponsor individual students by contributing to their school supplies and room and board. Secmol plans to establish its own residential school that would be partially supported by the work of its students.

Tourists have responded very favorably to Secmol's program, and it was able to pay back its loans during the first summer. The unrest of the summer of 1989, however, caused Secmol's income from tourism to fall.

The Gompa Association

One of the first groups to organize a response to the increase in tourists was the Ladakhi Association of Buddhist Monasteries, or the Gompa ("Monastery") Association. The group agreed to charge all tourists standard fees of 5 or 10 rupees (US $0.33 or $0.67) to visit the monasteries and to establish standard rules of behavior for visitors. After repeated thefts of religious objects, monasteries further restricted access; now tourists and Ladakhi visitors alike are met with bolted doors and locked trunks.

The Gompa Association, the government, and the community have united to prevent the further commercialization of the monasteries' religious heritage. Selling or exporting antiques is prohibited, and tourists' luggage is searched at the airport. A local ban was placed on the sale of religious art and ritual objects to tourists, but not all merchants complied.

Some monasteries earn money by selling seats at their annual festivals. Since most of the festivals, which feature several days of ritual dances performed by monks in traditional dress, are held during the winter when few tourists are in Ladakh, the practice is not widespread. When tourists buy tickets for the best seats at festivals, the Ladakhis in attendance are relegated to the status of second-class citizens.

The influx of tourist money has allowed the monasteries to make renovations and repairs at a time when the number of young monks is the declining. Sometimes the monks' choices of materials for renovation do not fit with tourists' expectations or with the traditional style: synthetic table tops, plastic floor coverings, cement steps, and bright, new, synthetic-based paints. Whether the new-found wealth will lead to corruption of the religious tradition, as some within the monasteries fear, or simply allow the monks to change with the times remains to be seen. If outward appearances change too drastically tourists may not visit.

Tour Companies

A number of Western-owned and - operated tour companies have attempted to mitigate some of the problems caused by tourists and to give directly to the people affected by tourism. Journeys, a US tour company, gave money to build latrines at popular campsites along the most frequented trekking routes, donated money to construct a religious shrine, and encouraged trip participants to donate winter clothing to be distributed in Ladakh. Other tour operators have distributed Ledge's tourist guidelines and arranged for their groups to visit the Center for Ecological Development.

Western tour companies have organized a number of tours focused on particular aspects of Ladakhi life. Several groups have come to stay in the monasteries and study Buddhism. The School for Field Research in Boston has organized visits of groups of students to learn about snow leopard ecology and the interaction of the local population with leopards. The Institute for Noetic Sciences organized a tour in 1989 (which unfortunately never materialized due to the unrest and bad weather) with the expressed purpose of learning about traditional ways of life, and the changes brought by development.

Information and Communication

The problems and responses associated with tourism in Ladakh suggest several areas to look at in assessing the impact of tourism: the information available to the parties involved, the distribution of costs and benefits, and the ability of those affected to influence decision making.

The lack of information and inadequate communication among Ladakhis, tourists, and others involved in tourism is an important factor in many problems related to tourism. Some Ladakhis, especially those in the villages, frequently do not understand why tourists visit Ladakh (at first some fear that tourists want to take their land). Others are eager to show their visitors that they are "modern" by prominently displaying their latest purchase, be it a plastic toy or a poster from the West. The resultant clash of cultures leaves tourists wondering how a society with such a cohesive and pleasing design aesthetic could allow such intrusions. As tourists begin to push farther in a search for the "real traditional culture," the cycle repeats itself. Ladakhis, in turn, have almost no knowledge of the fate of other non-Western cultures or that the process they are involved in is not unique to Ladakh (Norberg-Hodge, in press).

Tourists also tend to be uninformed about the history and culture of Ladakh, and the role of tourism within this context. They tend to see themselves as observers catching a glimpse of an exotic preindustrial culture through the briefly opened window of a vacation trip. This mind-set is reinforced by a variety of factors: a lack of prior knowledge of the area; the short duration of many visits; language barriers; visits that consist of brief forays into the realm of the villagers from the familiarity and comfort of Western-style accommodations; and a need to record the experience on film for the people back home.

Just as the Ladakhis do, tourists make judgments based on physical appearances and unexamined preconceptions. They tend to objectify the local people, seeing them as just another part of the landscape. Influenced by Western stereotypes of the Third World, tourists see Ladakhis as poor, dirty, deprived peasants struggling for existence and in need of development. Many assume that the large amount of money they have paid for their tour or hotel will inevitably benefit the "poor" they see around them. It is difficult for them to appreciate the environmental and social balance of the traditional system and the life of sufficiency and celebration that system allows.

Most tourists fail to see themselves as part of a continuous stream of visitors that is reshaping Ladakhi society. They know little about the inflation, divisiveness, breakdown of community, or internalized sense of poverty that tourism can bring. It seems quite normal to tourists that they should continue to consume in the same way on the Tibetan Plateau that they do at home, and, just as at home, that the system insure that they are separated from the environmental consequences of that consumption.

These generalizations do not apply to all tourists; in most cases, these attitudes are very difficult to overcome given the way tourism is currently organized.

Several of the local responses to tourism are aimed at improving education and communication: Secmol's and Ledeg's guidelines for behavior and information on culture and traditions, and Ledeg's educational programs seek to educate Ladakhis about life in the West and the impact of development on other cultures. Both groups attempt to provide opportunities for communication between tourists and Ladakhis.

Coincidence of Costs and Benefits

Tourism is widely recognized as having both advantages and disadvantages. The case of Ladakh shows that there is another dimension to the problem: the distribution of the costs and benefits. Most of the economic benefits of tourism in Ladakh accrue to a small group of people, and a significant portion of tourist money does not stay in Ladakh. The group that must bear the economic, environmental, and social costs of tourism is much larger and often includes different people than the group receiving the benefits.

Many of those responding to tourism in Ladakh are attempting to widen the distribution of tourism's benefits: the admission fees of the Gompa Association, Secmol's cultural shows and tours, Ledeg's restaurant and handicraft programs, and the direct donations of tourists.

Moving toward coincidence of costs and benefits is important not only for equity and fairness, but also for tourism to be managed in some optimal way in which incremental benefits exceed incremental costs. Many of the costs associated with tourism are impossible to measure and to translate into comparable units of monetary value. Comparing the advantages and disadvantages, although inherently problematic, is at least somewhat more satisfactory if the same people both pay the costs and experience the benefits. The two can be judged based on individuals' perceptions, without resorting to an abstract, economic calculus. Of course, this process will be viable only if these same individuals also have a voice in determining the evolution of tourism in the area.

The Gompa Association, Ledeg, and Secmol might help provide the organizational strength to lobby for reforms in tourism. Farther from Leh, some of the villages along trekking routes have organized to control tourism by restricting tourists to designated camping sites and collecting fees for the use of village resources. Further collective action might be possible, especially in villages where traditional cooperative structures remain strong.

Much of the power for shaping the future of tourism in Ladakh lies with the government. The government decides where tourists can and cannot travel, which infrastructures will be built in which areas, how tourism will be taxed and regulated, and how much effort will be spent on publicity. Usually those in government circles discuss tourism in terms of its relationship to national development plans. Indian planners subscribe to the prevailing developmental theories, those which look at tourism as an important foreign exchange earner and as an activity that is beneficial so long as tourist dollars stay in the country. Development planners usually pay little attention to the effects of tourism on minority cultures, and sometimes cite the influence of tourists in encouraging people to embrace "modern ways" as a benefit.

In Ladakh, where tourism has been a contributing factor to social unrest in a strategically important region, the government has strong incentives to pay closer attention to the effects of tourism as well as an economic interest in the continuing patronage of tourists. Since Ladakh's main attraction is its culture and natural environment, the government might be open to initiatives aimed at protecting either or both. Dealing with entrenched economic interests will not be an easy task. If, however, a coalition of local groups, tour operators, and government officials begin talking, new policies could emerge that would benefit all groups, including restrictions on absolute numbers of tourists visiting Ladakh and some controls that would distribute tourist impacts more evenly.

Sustainable Tourism?

An ecological, or sustainable, tourism implies that the human and natural ecosystems of an area will be able to adapt to the stresses of tourism in a way that does not threaten their continued functioning. A large influx of tourists with the money, material, and ideas this implies will inevitably affect a preindustrial culture. The issue of sustainability in tourism, then, seems to come down to whether the culture will adapt and yet retain its fundamental character through a period of change or whether tourists will destroy the qualities that attracted them in the first place and in the process leave the local inhabitants worse off.

Is tourism in Ladakh sustainable? That question is still open. Recent responses, which seek to bring new information and communication and work toward a coincidence of costs and benefits and more participation by all stakeholders, are a step in the right direction. The forces pushing the other way, however, are varied and strong. Increased inequality and a commitment to a Westernizing development have led to many social and environmental problems elsewhere. Although tourism is not the sole cause of these trends, it is certainly a factor.

Real change toward a more sustainable tourism will come only when tourists change their attitudes. The West must come to accept other cultures as different yet as having equal validity. When tourists view residents of the Third World as individuals like themselves, and when they arrive with open minds, ready to learn and be transformed in a spirit of solidarity, then tourism will not change a place so profoundly.

Notes

This assertion is backed up by the results of an informal survey of tourists conducted by Ledeg and the Ladakh Project at the Center for Ecological Development in Leh during the summers of 1986 and 1987. The survey is not a representative sample of all the tourists visiting Ladakh, since only those tourists with the time and inclination to visit the center were included. Individual travelers are overrepresented, and those traveling with prearranged tours are underrpresented. English-speaking tourists are also over represented. The survey showed that: (1) 45 percent of the tourists responding admitted having poor or no prior knowledge of Ladakh. Only 10 percent considered themselves to have a good knowledge of the region. For 90 percent it was their first visit to Ladakh; (2) 75 percent reported that they had not been able to establish more than superficial contact with the local residents; and (3) 86 percent favored additional controls on tourism.

References

Ladakh Project

1988a Ecological Steps Towards a Sustainable Future. Bristol, England: the Ladakh Project.

1988b Ladakh in a Global Context: Energy. Bristol, England: the Ladakh Project.

Norberg-Hodge, H.

1988 Ladakh: The West Comes to the Himalaya, Stockholm: Hagaberg. In Swedish.

Pitsch, H.J.

1985 The Development of Tourism and Its Economic and Social Impact on Ladakh. Master's thesis, Heilbronn Polytechnic, Heilbronn, Federal Republic of Germany.

Secmol (Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh)

1988 SECMOL Presents Pride of Ladakh: Glimpses of the Art and Culture of the Land. Leh, Ladakh, India: Secmol.

How You Can Help

If you would like to inform others of the issues discussed in this article or support the initiatives presented here, you can contact the following organizations:

The Ladakh Project

21 Victoria Square P.O.Box 9475

Clifton, Bristol BS8 4ES Berkeley, CA 94709

England USA

Distributes: "Guidelines for Tourists"; "Development, A Better Way?: Lessons from Little Tibet" (30-minute video); various project publications; newsletter; cassette of Ladakhi music.

The Ladakh Ecological Development Group

Leh, Ladakh 194101

Jammu and Kashmir

India

The Students' Educational and Cultural

Movement of Ladakh

SECMOL Compound

Leh, Ladakh 194101

Jammu and Kashmir

India

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.