The Garrison Dam, conceived in the 1940s and constructed in the 1950s, has had the greatest impact on the Indians of Fort Berthold, North Dakota, since the nineteenth-century smallpox epidemics reduced their numbers to near cultural extinction. Nearly one century later, the Three Affiliated Tribes-Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara-had successfully recovered through intermarriage and cultural replacement. They preserved their distinct cultural traits-through the early reservation period, despite conscious efforts by the Department of War (formerly the overseeing body of Indian affairs) and Christian missionaries to eradicate native beliefs and practices.

By the 1950s, the Army Corps of Engineers, with the cooperation of the US Senate and Congress, had implemented the Garrison Dam project. As a consequence of this project, the newly recovered tribal economy was effectively destroyed; its impact can still be felt in all aspects of contemporary Indian thought and action. More than 90 percent of the population was relocated to accommodate the dam. The dam produced visible effects on native economy, health, housing and social cohesion. Contemporary reservation life bears witness to the effects of resettlement through families whose members span the generations from the pre- and post-dam periods. In order to appreciate these effects, a glimpse into reservation life prior to construction of the dam will introduce the unique and complex life of the Three Affiliated Tribes.

Historical Overview

The history of the Fort Berthold area since contact with Euro-Americans involves intertribal warfare, smallpox epidemics, flooding of reservation lands and the eventual relocation of what came to be the Three Affiliated Tribes.

Before the first smallpox epidemic (1782), the Hidatsa, Mandan and Arikara were distinct groups, each comprised of independent bands that occupied separate and autonomous village sites. These groups frequently sought alliances among themselves and other groups in order to unite against warring Sioux. After the second major smallpox epidemic, the Mandan and Hidatsa groups united and moved north to the site of Fort Berthold, where the Arikara joined them in 1862. The period from 1845 to 1886 was wrought with famine, social disorganization and dependence on white traders.

In 1876 the first resident missionary arrived at Fort Berthold and established the Congressional Church of Christ, an event that marked the beginning of rapid and widespread missionization by Protestant and Catholic clergy. Social organization became structured around "village-church" complexes that coincided with the decline in traditional age-graded societies and attempted to replace matrilineal clans with nuclear family structures. Shifts in occupational roles tended to mirror American frontier motifs, whereby men became admired as cowboys, ranchers and soldiers and women were rewarded for their domestic accomplishments.

Conflicts in this early reservation period not explored in the existing literature involve the reversal of gender-based occupations, by which men were taught modern techniques of farming, thereby encroaching on what was traditionally the domain of women. Furthermore, factionalized conflict developed between traditional and "white-oriented" Indians. An example involves the dissolution of the Black Mouth society (a native organization that enforced ceremonial obligations and culturally appropriate behavior) and the installation of a tribal police force charged with the task of halting any ceremonial dances. These clashes often resulted in bloodshed or death, finally dividing communities and disrupting kinship relations.

Through these hardships and an ensuing social reorganization, assimilative forces had successfully converted a semi-sedentary horticulturist and warrior society into full-scale agriculturists and wage laborers. By the 1920s, ranching and farming economies had taken hold, and Indians successfully competed in the cattle industry of North Dakota. Throughout this pre-dam period, the Three Affiliated Tribes maintained a lower alcoholism and welfare rate than neighboring whites. Women had incorporated the new materials and techniques of church sewing circles, and elevated "arts and crafts" to high levels of artistry. Men became expert equestrians and heroes of both world wars.

By the 1930s, government and church education programs stepped up efforts to enforce compulsory English language programs. Despite negative effects of intergenerational conflict and associated culture loss linked to native language loss, the use of English facilitated communication among the three tribes. The establishment of a tribal newspaper further allowed for reservation-wide communication regarding important decisions affecting tribal rights, such as the proposed Garrison Dam.

Up to this point, the Three Affiliated Tribes were forced to adjust to the upheavals of disease, missionization, a disrupted economy and reservation life in general. It was at a point of remarkable demographic and economic recovery that plans for damming the Missouri River were being considered along reservation lands throughout North and South Dakota - lands that had been protected by treaty since the 1800s. Land issues and fictionalized conflict discussed above were renewed and exacerbated by the removal of people, homes and community services built up through intensive periods of cultural assault and adjustments. Additionally, many sacred shrines, not then protected by the Indian Religious Freedom Act and the National Historic Preservation Act, were forever submerged under the floodgates of the Garrison Dam.

The Land Base

The first cession of lands by treaty was accomplished by the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty; it designated 12,500,000 acres of reservation lands between the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. Through subsequent government actions, this acreage was reduced to 640,000 by 1910. In his Ph.D. research for Harvard University, Reifel noted that "since their first treaty at Fort Laramie...they have relinquished title to an area greater than that of the states of Massachusetts and New Hampshire combined".

As early as 1944, Congress designed a "Plan for the Development of the Missouri River Basin" that was outlined by Public Law 534. Deliberations ensued without Indian input on two plans submitted under the Flood Control Act; Col. Lewis A. Pick and W. Glenn Sloan each submitted recommendations for suitable taking areas for Missouri River dam construction. White opposition mounted and joined with Indian opposition during the time that Sloan's surveys favored predominantly white settlements. Ultimately, a joint resolution in which Col. Pick imposed his plan on the Army Corps of Engineers was enacted, incorporating some of Sloan's recommendations but ignoring his assessment to leave out tribal holdings. White support of Indian opposition to the dam declined radically with Congress's acceptance of the "Pick-Sloan Plan." The final plan involved the taking of tribal lands and promised flood control and hydroelectrical improvements for Indians and surrounding white communities.

In 1947, the 80th Congress approved PL 296 which appropriated funds for "Flood Control, General." A contract was drawn up in 1948 for approval by the Three Affiliated Tribes. Indians feared that if they failed to consent to outlined terms, they would receive less adequate compensation in the future. In tears. Council Chairman George Gillette "consented" to the coercive piece of legislation. "The truth is, as everyone knows," he said, "our Treaty of Fort Laramie...and our constitution are being torn to shreds by this contract". By 1949, provisions for compensation were passed by the Senate and the House and signed into law by the president. In 1950, the tribes voted 525 out of 991 adults to accept the provisions of the act.

By 1951, construction was underway and relocation procedures undertaken. The 1951 population included 356 families on 583,000 acres of reservation. Three hundred families were forced to relocate from more than 153,000 acres of flooded lands. The US government believed that many families would choose to permanently move to urban areas under federal job training programs; however, cultural forces inhibited migration to the extent that many Indians viewed even the new reservation lands as "foreign" and inhospitable. Those who did migrate returned in much greater numbers-than anticipated.

The loss of agriculturally rich bottomlands has continued to alter the overall way of life of what were previously a self-sufficient people. Moreover, the taking area included important natural resources that figured highly in the Indian economy: the floodplain timber that provided logs for houses, fence posts and natural cover for wintering livestock; the wild fruits and berries; and the game that supplemented the Indians' food supply. Water supplies were replaced by drilled wells that have proven inadequate and often dangerous for drinking. A recent (1987) panel discussed the health effects of the high alkaline water that many people have been forced to drink over the years:

On the river bottom we had plenty of water to drink, wash and water our livestock. When we were forced to move to the upper plains, wells were dug so deep that you could not pump them by hand...When we moved to the prairie, we could no longer eat the chicken eggs...they were blood red because of the water! The water was not suitable even for animals.

The poor water supply has forced many residents to move from the rural countryside to the hub of reservation activity at New Town. Moreover, the building of the dam created land segments that physically divided portions of the reservation from one another, resulting in fragmentation that renewed old tensions and created new factions.

The relocation severely disrupted Indians' cultural beliefs and practices. The Mandan and Hidatsa, for example, share origin myths that expressly foretell of continual migration upstream along the Missouri River bottomlands. Archeological evidence reveals migration patterns in corroboration with these beliefs. The construction of the dam thwarted their movement. Although developers did make some effort to relocate cemeteries and shrines, these were largely associated with Christian churches and monuments. Baby Hill, a grave site for infants and a prayer site for women who hoped to become pregnant, is irretrievably submerged below the dam. Additionally, clan burial sites, where skulls were placed in a circular formation to mark the cohesiveness of clan bonds, have also been destroyed by the dam.

Many structures, such as the long-promised hospital, have not been forthcoming and others have proven inadequate. Modern, unfamiliar and poorly constructed housing structures have contributed to the social disorganization initiated by relocation. Housing authorities recommended replacing the (by then) "old-style" log houses with prefabricated government housing units. Some people opted for moving their houses to the new reservation. As Iva GoodBird recalled:

I was in the middle of giving a cosmetics party when they came...they told us we had to leave in the morning. [So] we spent the whole night packing and in the morning we woke up to jackhammers.

Iva and her family followed their house to where it still stands today near New Town. All but the doghouse was transported.

Final relocation was completed by 1955; by 1960 there was a marked decline in the standard of living. By this time, only 19 percent of the population still lived in log houses; 53 percent occupied frame houses, described as poor or fair. By 1967, more than 90 percent of the housing was classified as substandard; 87 percent of the homes lacked a safe, sanitary method of refuse disposal; and 81 percent of the people had to carry water a half-mile or more.

These conditions, coupled with a growing dependence on a cash economy and a shift in nutritional goods from fresh goods to government commodities, have several repercussions: Indians rely increasingly on federal welfare programs, and poor health conditions, increased alcoholism and crowded living conditions abound. Federal Housing Authority policies have forced elders to sneak their family members into units designed for solitary living-a concept not only foreign to, but considered inhumane by even the most "nontraditional" Indians.

The conflicts between traditional values and contemporary problems have resulted in physical distress and psychological unrest. Examples range from diabetics who must travel more than 200 miles for dialysis treatment twice a week to families who have been forced to lease their lands to white ranchers who can better afford the necessary equipment and labor. Today, tribal priorities include claims to land-use areas surrounding the dam and the continuing struggle to obtain just compensation, both monetarily and in "equal value" development strategies. These involve recent meetings of Tribal Chairman Ed Lone Fight with the Army Corps of Engineers to discuss profit sharing from a growing tourist industry and tribal control over the shoreline.

Diverted profits are a common result of industrial development, in which revenue is exported away from the reservation land base and reinvested in non-Indian business ventures. For example, the Army Corps of Engineers benefits from the leasing of "resort" land to developers along the shoreline of the Garrison Dam. As Tribal Chairman Lone Fight has remarked:

When the Garrison Dam was built the Corps' concerns were flood control and hydroelectric-power...[but] Corps [officials] are just land brokers...high geared real estate brokers.

Ambler (1980) has pointed out that the critical concern of CERT (Council of Energy Resource Tribes) and the tribes was "not so much the value of resources, but who controls them." The continued efforts of the Fort Berthold tribes, as exemplified by recent reservation hearings, illustrate this concern and the will of native people to act on their own behalf toward their desired goal-control over their own natural resources and lives.

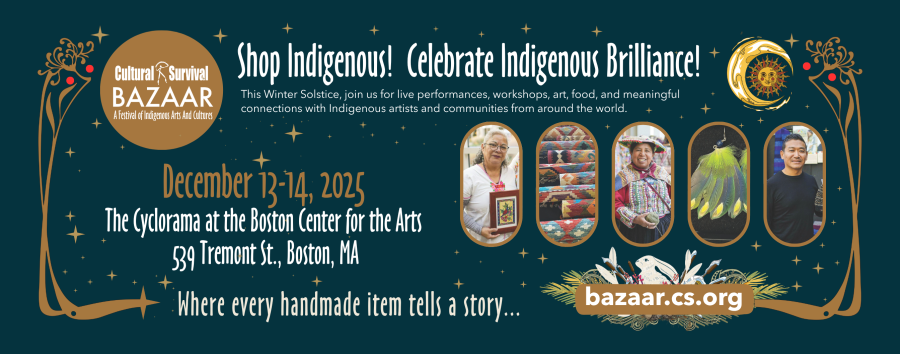

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.