In the early morning of November 20, 2012, Paraguayan national police entered the Avá-Guaraní community of Yva Poty in eastern Paraguay armed

with an eviction notice—setting off an ignominious chain of events in the community’s three decades-long struggle to gain title to their lands. Homes were

burned, wells were poisoned, a school was destroyed; an entire community was seemingly reduced to a pile of rubble and ash.

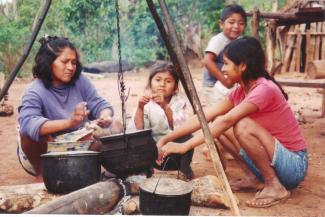

Residents of Yva Poty have long suffered difficulties while endeavoring to live their lives on their own terms in their ancestral lands. The community, whose name translates to “flower of the fruit,” was founded in the early 1980s by the respected shaman Avamainó. In 1983, Avamainó, along with his wife and her brother, left the Avá-Guaraní community of Mbói Jagua due to resentment over the strong missionary presence and influence there. They wanted to be free to live as they saw fit, including the freedom to practice their own religious beliefs. Taking their families with them, they created a new community in their ancestral lands: Yva Poty. Avamainó continues to serve as Yva Poty’s spiritual leader, while his son, Rogelio has long served as the chief in legal matters.

In 2005–2006, the owners of the Arroyo Mokói ranch contested the ownership of Yva Poty’s land, despite the fact that Yva Poty is recognized by the Paraguayan government as legitimate as evidenced by the creation of a school under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and Culture by Resolution 1624, enacted on September 23, 2002. Such contention has created a tense atmosphere for the many Indigenous people in Paraguay (and elsewhere) who are faced with

constant insecurity regarding their lands.

Working with the National Institute for Rural and Land Development, Yva Poty relocated to land purchased in 1994 by the National Indigenous Institute for Avá-Guaraní people. The move became official on December 4, 2006, and community members were happy to have the security of living on land with the title held by the Institute, and by the road to more easily sell their surplus crops. In the intervening years, however, claims have been made against both Yva Poty and the Institute, with the assertion that the land title is false.

Outsiders commonly use this strategy to claim Indigenous lands in Paraguay, and until recently these problems were mainly a nuisance to Yva Poty, but that changed dramatically last November.

On November 20, Paraguayan national police entered Yva Poty land with a Brazilian man named Paulo Ferreira de Souza, who held an eviction notice signed by Judge Carlos Goiburú Bado of Curuguaty. Ferreira De Souza had been contesting Yva Poty’s title for some time and had recently invaded the community’s land, beginning mechanized development to plant soy on 15 hectares while also limiting community members’ movements within that area by way of constant threats. With judgement in hand, the police entered the school during morning classes and ordered an evacuation of the building. As the national police—reportedly 400 from around Paraguay—cordoned off the road, hired Brazilian farmhands began demolishing buildings with chainsaws, beginning with the health center then moving to the school.

They proceeded to burn all school supplies—books, notebooks, student records—and destroy desks, chairs, and blackboards, lowering and burning the Paraguayan flag in front of the children. Ostensibly this last action was intended to instill a sense of hopelessness in the community, a signal that nobody,

not even the Paraguayan government, would do anything to help them. While this was happening, neighboring residents were stealing Yva Poty members’ possessions, including their domesticated animals and crops from their fields. According to reports by the Ministry of Education and Culture and the

National Indigenous Institute and the popular press, they even poisoned the community’s wells. In total, approximately 35 buildings were destroyed, among them the homes of 170 people. Police controlled the community members, taking Rogelio away and reportedly beating him for several hours.

One old man who refused to leave his house would have been burned alive inside, but younger community members removed him to safety. Francisco, Avamainó’s grandson and director of the school, detailed the horrific chain of events in the Ministry’s executive report of November 26, 2012:

“... a strong police contingent arrived in the company of a Brazilian citizen named Paulo Ferreira de Souza, with orders to evict more than 40 families from a settlement they inhabited for more than 22 years, without any type of notification; they beat our leader, Don Rogelio Sosa. This land is 600 hectares, and was purchased by INDI in the year 1997 [sic.], for the Avá-Guaraní people. Mr. Paulo Ferreira de Souza came afterwards with 30 farmhands, who are our neighbor whom we [previously] provided manioc, corn, and beans; they were the ones who demolished all of our homes. [Mr. Ferreira de Souza] paid them 300,000 Guaranies [about $70] per day. Moreover, the Police who participated in the operation received 60 liters of fuel, provided by Mr. Paulo Ferreira de Souza ...”

In conjunction with his father, Francisco petitioned the Ministry to reconstruct the school and to replace all of the lost school supplies. The men also asked for 20 million guaraníes (approximately $4,700) and denunciation of Judge Carlos Goiburú Bado along with the National Deputy, Andrés Giménez, for his logistical assistance to the police, hired Brazilian farmhands, and Ferreira de Souza.

Preliminary investigations have uncovered numerous legal irregularities in the case, one of which involves Judge Goiburú Bado’s overturning of his decision the day after eviction. Just one day after the wanton destruction, community members were encouraged to return to Yva Poty, although they were understandably reticent initially. The Ministry was also quick to condemn the actions of the interlopers and formed a judicial team the following day. Non-perishable food was provided to the community, the school was immediately rebuilt, and electricity restored. As the rebuilding of Yva Poty continues, Rogelio reports that “everything is tranquil now.” Two of the community’s five wells provide potable water, and they have sufficient corn and beans to feed themselves along with food that they are purchasing with wages earned. The people of Yva Poty are seeking compensation for the destruction and theft of their property. They have begun rebuilding their homes, including the o’y guasú (great house), but will not be awarded any legal judgments until February at soonest, as January is a national judicial holiday. This case will undoubtedly set an important precedent for other Indigenous communities in Paraguay also facing claims against their lands, with or without title. And for this reason, perhaps above all others, the resilience of Yva Poty is not simply inspiring; it is a cause for hope.

View photos of the destruction here: goo.gl/baQd4.

— Eric Michael Kelley is a visiting researcher and lecturer in anthropology at Boston University.