The follwing are excerpts of interviews conducted at Respecting Our Traditional Science and Ways of Knowing event.

Áslat Holmberg (SAMI)

MEMBER OF THE SAMI COUNCIL, FINLAND

I am from the northern part of Europe. The land of the Sami encompasses most of Norway, Sweden, part of Russia, and Finland. It’s a very cold area, an arctic or subarctic region. There are many lakes that get frozen over. We have lots of snow on the ground, white gardens; very long winters, very light and short summers, not a lot of sunlight. But the winter has been getting much shorter, and spring is becoming longer. We’ve had a lot of irregular weather with very low or very high water levels. Last summer was exceptionally warm. These irregular weather patterns are happening during winter, and the rain in the winter is affecting the pastures.

I’ve been working occasionally with the Sami council as a youth representing the council. When the Paris Agreement was being made, I was involved with youth politics representing the Finnish youth organization. After participating in this, little by little I have been receiving more invitations to participate. The Paris Agreement is a global agreement to stop or slow down climate change, to force the States to do something.

If you want to see some change, you can change your own behavior and lead by example. Also, be mindful of your actions and how they impact the environment and climate. I think it’s really important to acknowledge that there will be changes; some things we cannot stop. So it’s [our responsibility] to educate ourselves and know what kinds of changes could happen in our communities and environments, so that we can prepare for what’s to come.

What I came to learn already in the first days is that people might not be aware that there are Indigenous Peoples in the north of Europe, that there are Indigenous People that are white. That’s something I have also come across before. We share a similar kind of history of colonialism and marginalization with Indigenous Peoples all over the world.

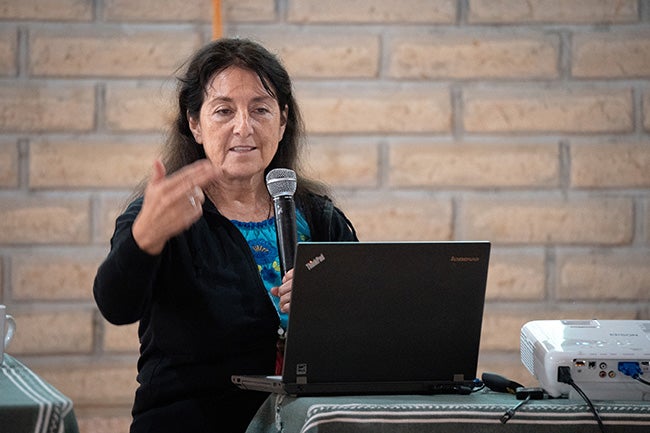

Andrea Carmen Valencia (YAQUI)

INTERNATIONAL INDIAN TREATY COUNCIL EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

The issue of food sovereignty intersects with other issues. This is one of the four main issues we address at the International Indian Treaty Council, along with human rights, environmental health, and treaties, together with international legal regulations. The issue of food sovereignty is very important; it is one of the principles that contributes to the self-determination of our peoples, because without such sovereignty it is not possible for us to feed our children. It is not only about the food itself, it is also spiritual. For the Maya, for example, corn is not only the great food that nourishes our body, but corn is also the first source of creation. The introduction of genetically modified corn in Guatemala is a problem especially if it is not understood that corn is the spiritual base of the Maya people; the problem is not solely a matter of nutrition or the economy of the communities. We are dealing with an issue closely linked to the right to land, water, the seeds themselves, and the problem of climate change and environmental pollution, together with the fight against extractive industries.

For years we participated together with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in the matter of food security. Now we have a committee with the participation of the Indigenous Peoples themselves where they can present their complaints, but above all contribute to set concepts born of several questions: What is sustainability? What are human rights? What is the protection of the environment? We have participated in global conferences on climate change and we have noted the good handling of data from Western scientists, but Indigenous Peoples have their own science, connected since ancient times to the observation of the biological cycles of Mother Earth.

Our science can be combined with other forms of knowledge in our communities and in the international field. On one occasion I was in the house of Anselmo Valencia, then leader of the Yaquis, and he took me to the back of his house where he showed me a little bit of little black corn. He explained that everyone prefers to grow yellow corn and has neglected the cultivation of black corn, corn that needs very little water and whose technical management has been transferred from generation to generation. Here is an example of our science to be shared with the world.

Celia Alicia Ramos Carrasco (ZAPOTECA)

YURENI A.C., OCOTLÁN DE MORELOS, OAXACA, MEXICO

I work in an environmental and human rights organization. One of the reasons I decided to come to this event is because the topics we are working with coincide with the issues that are being addressed now. We are a group of women who are working with environmental issues, with the objectives of human rights and environmental justice.

I joined the association because of my thesis topic, which has to do with the impact of climate variability on maize crops in acampesino community in the Sierra. When I joined the association I started to relate with people who shared my concerns and could contribute to my research. Events such as this one address issues such as climate change, food sovereignty, and traditional ways of life of communities.

I’ve seen how food sovereignty has been undermined in the community where I come from, Ocotlán de Morelos. Now it is a community with more and more merchants, so much so that the production of food has been put aside. There are

farmers, but they are now a minority. The issue of food production is one of little importance, almost ignored. Worse, large companies have appeared, like certain wineries, that supply you with food.

Having gone to live in the Sierra Juárez made me reflect on what is happening to us in Ocotlán, why we are not producing food. Establishing a contrast between my town of Ocotlán and the Sierra Juárez motivates me to start taking action in favor of food sovereignty. If it is not done, we will have difficult conflicts. We already have problems, so much so that Ocotlán is part of the Association of United Peoples for the Defense of Water. The idea is to be able to rationally manage the resource of water in favor of the common good.

Ocotlán is close to another place that is completely agricultural, so we have to do something. I do not know yet what it will take to reinvigorate agriculture in the short and medium term; but I am interested in planting. It’s real that my family sometimes lacks food and that water is bought in carafes. It is a situation that has become a common experience. When there is no water, when it’s over, we will not be able to buy it anymore. What will we do? You have to be aware of all this.

Emigdio Ballón (QUECHUA)

AGRICULTURAL DIRECTOR, PUEBLO OF TESUQUE

In Bolivia, I studied agronomy with a specialization in genetics, graduated as an engineer, and I worked as the national coordinator of the Andean Crops Program. It is clear that our ancestors have done for thousands of years what we learn in college about selection and all those questions. You can see it with corn, its flavor and color. [For example], the Jope corn is a small corn that grows only three feet in height, and the quality changes with quite large ears. For me, there is nothing comparable to traditional crops. Our grandparents already knew organic agriculture; they did not use pesticides.

In 1974 or ‘75, an event was organized in the Lipes community called the National Quinoa Festival, and I shared a bedroom with a professor at the University of Colorado. We exchanged opinions, and this was how the quinoa farmers’ cooperative was organized. I ended up going to the United States to do research on quinoa and amaranth grains. In the United States, I worked with a small NGO that devoted itself to the collection and trade of seeds but had to close due to lack of funds. Our idea was to distribute these seeds for free, but it did not work and in the end a corporation bought the seeds. It is part of the first company of organic seeds in the United States, perhaps in the world.

Later I worked with a film producer on medicinal plants knowledge that I acquired from my parents, grandparents, and my mother in particular, who had a lot of knowledge in medicinal plants. She was a healer. Some Native friends from the United States suggested that I work with them in a community called Tesuque in New Mexico, and I have been with them since. I am currently the director of the natural resources program. We created a seed library and the documentary film, Seed: The Untold Story.

I met an Argentinian man who came to Seeds of Change, a company I helped found, and I gave him seeds to take to Argentina. He passed through Mexico and Guatemala and left seeds in those places and others. He brought seeds to Huicholes brothers and he always stays in Peru.

The seed bank was an achievement. In the Tribe where I work every year, the council and the governor have changed; some have supported us and others do not. There are a number of difficulties, but in spite of that, when you believe in divine power, things done with good intention come to a conclusion. Thanks to some foundations, like the First Nations Development Fund, the seed bank could be built. We have solar energy, rescue and harvest water, a fruit dryer made with solar energy, and the seed library is made of recycled material and runs on sustainable energy. The walls are made of bales of straw, so we do not need an artificial system to maintain the temperature.

Who controls the seeds, controls life. I know because Alejandro, the Argentine friend, walks the seeds through other territories where I deposit them. The seed bank is very important. You do not have to have all the seeds, but the most important ones for the use of our communities. Food sovereignty is to produce what we eat, what our grandparents ate, which is what has kept us alive.

Berenice Sanchez (NAHUA/OTOMÍ)

ASSEMBLY OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES FOR FOOD SOVEREIGNTY PRESIDENT, MEXICO

I was involved in a national effort to consult Indigenous Peoples of Mexico about their positions in relation to climate change [to ensure] our knowledge and traditions were taken into account. Speaking of climate change in academic terms with an economic focus has been a challenge, because for us, the issue is not so complicated. I do not know if this complexity is created intentionally to keep us away from the subject. Our traditions and daily experience with climate might not be academic or done in the cold offices of meteorologists, but Indigenous Peoples have always depended on the full understanding of the seasons to survive and have accumulated knowledge throughout the centuries based on observations.

Everything, absolutely all the factors, has been observed and interpreted to predict the dance of the rains, the droughts, the frosts, the winds, the light, the moon, the sun. Indigenous Peoples enjoy the tradition of reporting the climate and understand, based on these reports, the ABCs of what we now call climate change. We know of birds that migrate to our forests; some of these bird species have not even been registered by the national authorities. For us, this bird is a carrier of knowledge that has been cemented with our observations. We have specific knowledge about our territories, and in the face of the current climate crisis we can deduce responses originated in our communities. What we offer is science, because we have systematized and interpreted these observations.

It is very important, the sharing of responsibility that affects Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples cannot be accused of causing the current crisis, nor can we accept that our forests have become a dumping ground for carbon emissions. Our territories should not be considered a garbage dump. We must be fair in assigning responsibilities to those who have the greatest impact with their carbon emissions. For example, the United States must assume the greatest share of responsibility; the same goes for Switzerland, Germany, and Mexico. It is incongruous with reality that these responsibilities are charged to Indigenous Peoples.

The strength of Indigenous Peoples is found in our traditions, in our devotion to Mother Earth, in our wisdom, in our spirituality. This is a small light for the rest of humanity. This fight, while dangerous in Mexico—one you can get killed for—must also be carried on by our children in memory of our grandparents, so that these same young people do not get lost in modernity with their cell phones, but always return to the common house that we have built over many centuries.

Rafael Avendaño (MIXTECO)

COOPERATIVA DEL CARACOL PÚRPURA, PINOTEPA DE DON LUIS, MEXICO

We have worked this trade of purple snail milking for many years; it is a millenary tradition of extracting purple dye from the snail that our ancestors left us. I am the third generation of my family in this profession, and we face the serious problem of the overharvesting of this mollusk by the people who live in the area. We are the carriers of the knowledge and technique of how to relate to the purple snail. The Mixtecos keep the tradition of respecting the land, the sea, and the moon, with which we work according to their cycles and their relationship with the sea. Biologists and anthropologists have learned from us the empirical knowledge that our ancestors left us. Books have been published about our knowledge in this subject and in other fields.

In 1982, Indigenous Mixtecs sued a Japanese company, Purple Imperial, which arrived in Mexico a short time before to extract the dye from the mollusk. Soon, their activity resulted in massive deaths of the snail. Fortunately, in 1985 we had a victory with the recognition of Mixteco efforts to conserve the environment, and we were authorized to legally enter Huatulco National Park.

As Indigenous people, we have the best techniques to live in harmony with nature, how to work the land without hurting it, how to live with animals without killing them, and how to fulfill our food needs without harming trees. We have a lot of knowledge and skills, such as the engravings on jícara fruits. Today, we face a very serious problem: people are coming to the area to harvest the purple snail, which is considered a delicacy. What will happen in two or three years when the purple snail becomes extinct? What will happen is that it will end a millenary tradition of Indigenous Peoples. For us, the Mixtecos, the purple color is sacred, symbolizing the purity and fertility of Mixtec women.

We want to educate the people of the area and local restaurants, especially the people who do not know the importance of the purple snail in Mixtec culture. We are aiming for a 50 percent reduction in the consumption of the snail. Based on a public awareness campaign, talks, posters, radio spots, and a triptych we are doing, we can achieve this percentage. Humans are very quick to destroy. We have been fighting for the snail’s survival since 1985 and have done it with our own resources, with our own money, using the money we make from selling our engraving toward our legal fees. Thanks to a Keepers of the Earth Fund grant, we hope to continue generating a positive impact in this campaign.