By Richard Arghiris. Reposted from Intercontinental Cry.

"They have destroyed our Indigenous crops and the government has done nothing to stop it,” said Elivardo Membache, an Emberá Cacique who is fighting to protect his ancestral lands from illegal settlers.

“Every day, communities are being invaded… They fence off lands and begin farming and ranching. This affects more than 3000 Indigenous families, their personal safety, their territorial integrity and their cultural unity…”

On Friday, October 5, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) held a public hearing on the theme of collective land titling in Panama. It was attended by civil society organizations representing the Emberá, Wounaan, Guna, Buglé, Ngäbe, Naso and Bribri Indigenous Peoples.

Membache, the Cacique General of the Congreso General de Tierras Colectivas Emberá y Wounaan of Panama (General Congress of Emberá and Wounaan Collective lands of Panama) – an organization representing traditional Emberá and Wounaan lands outside of Panama’s Comarcas (semi-autonomous Indigenous territories) – told the commission that his people have been campaigning for collective titles for a generation.

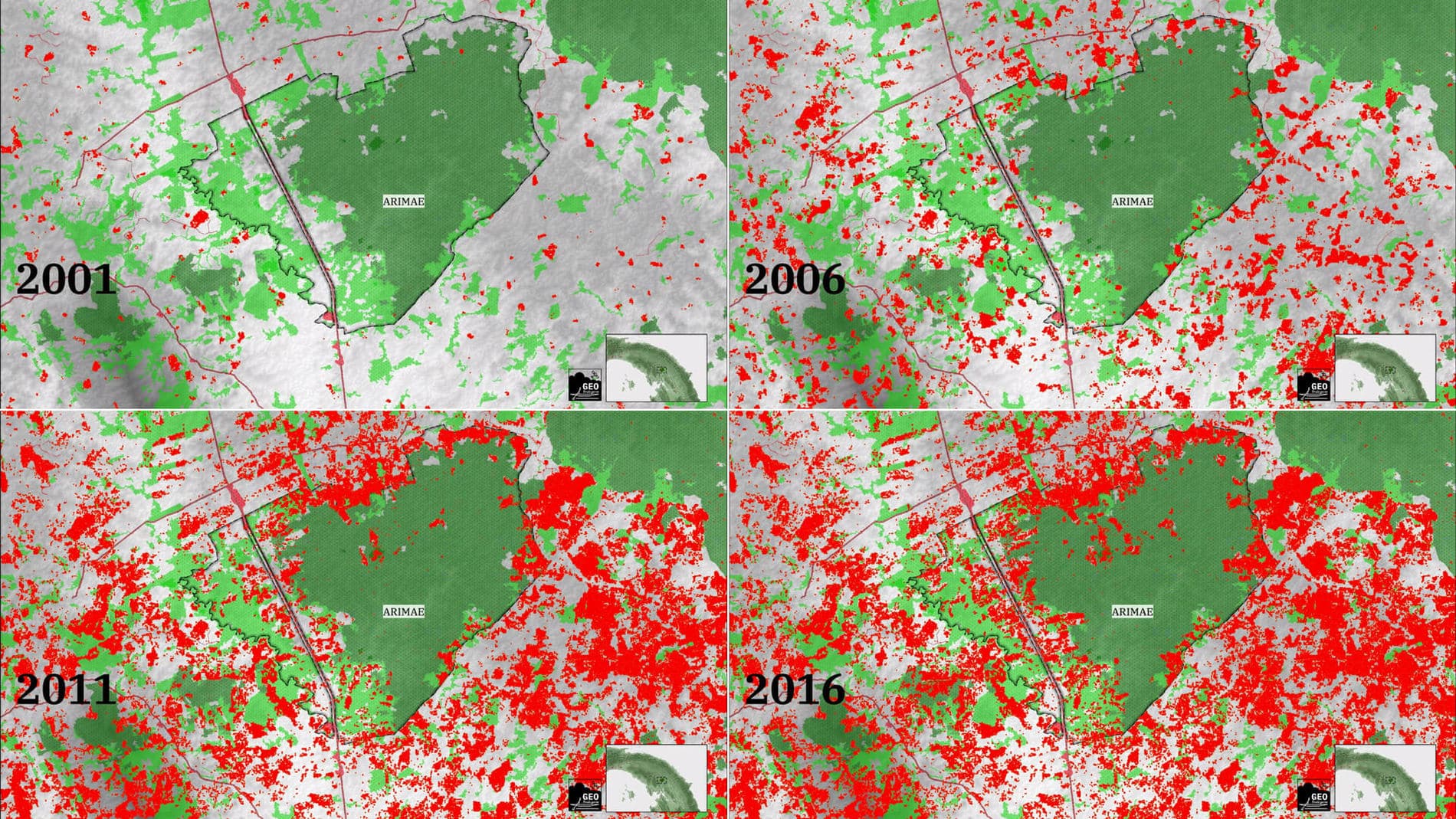

He said that delays in the titling process had resulted in the ‘invasion’ of settlers on their lands, which include ecologically sensitive areas of primary rainforests in the frontier zone of Darién in eastern Panama. Maps compiled by the New York-based environmental NGO Rainforest Foundation revealed the shocking extent of deforestation in parts of the region from 2001 to 2016.

Deforestation timeline around the community of Arimae. Courtesy Rainforest Foundation

The titling process is currently stalled because, according to Panama’s Ministry of Environment, Emberá and Wounaan traditional lands fall within protected areas such as the Darién National Park. Membache called the situation “absurd.”

Membache also suggested that the State was fueling land grabs by encouraging Indigenous inhabitants to obtain individual titles to their lands – an approach that undermines communal ownership and opens the region to private acquisition.

“Even more serious is the fact that the government is promoting individual land titling within our communities,” he said, “which makes it easier for our brothers to sell their lands… [Furthermore] the government is pressuring us to reach agreements with the invading settlers. When we reach agreements they provide titling to the settlers, but not to our communities.”

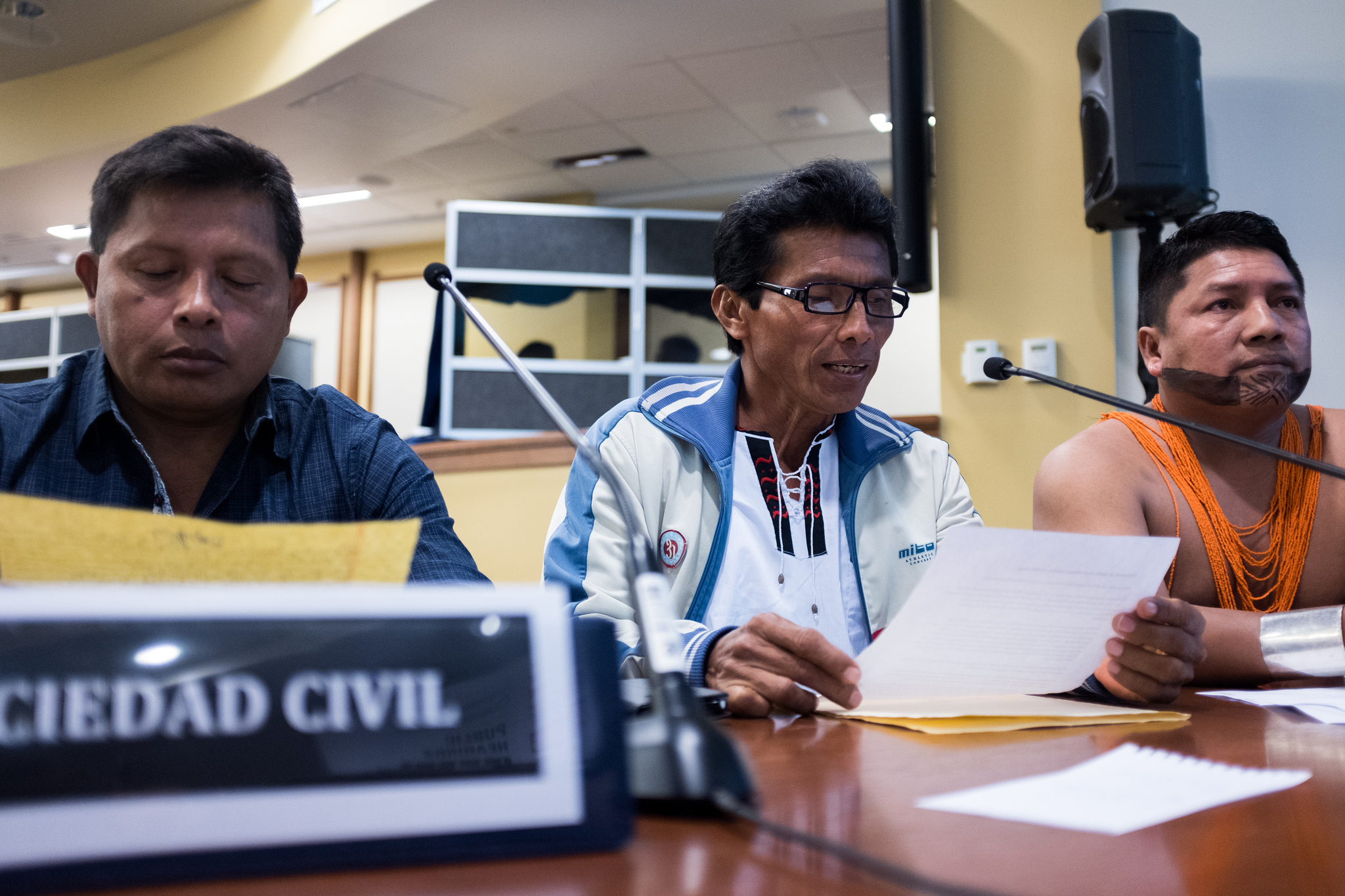

Cacique Elivardo Membache. Photo: CIDH/flickr (CC)

In fact, a handful of Emberá and Wounaan communities have received collective titles since 2012, including Puerto Lara, Arimae and Caña Blanca. Three more were green lit in 2018, but only after Wounaan activists staged a two-day protest at government buildings. According to Membache, the titles cover approximately 11 per cent of their ancestral territory.

Meanwhile, Adolfo Villagra described development plans for the Río Teribe area of Bocas del Toro in western Panama as “the nail in the coffin” for the 3000-strong Naso people.

Known as Tjër Di (Grandmother Water) in the Naso language, the Teribe river is the central axis of Naso society, a source of spiritual and material sustenance for generations of Naso. The Indigenous communities living on its banks have been campaigning for collective land rights for more than four decades.

“We have exhausted all necessary recourses,” said Villagra. “We’ve held marches and walks and we’ve presented petitions to the national assembly.”

From left to right: Feliciano Santos, Adolfo Villagra, Cacique Elivardo Membache. Photo: CIDH/flickr (CC)

In fact, Naso ancestral lands are somewhat extensive. They encompass pristine rainforests and partly fall within two protected areas: the Bosque Protector Palo Seco and the Parque Internacional Amistad.

Despite the protected status of these areas, the Panamanian state has commissioned divisive and ecologically destructive hydroelectric projects on tributaries of the Teribe. These include Bonyic dam, a 32.64 MW gravity dam owned by Hidroécología Teribe and Empresas Públicas de Medellín, and a project currently known as Teribe 500, which has been slated in Panama’s national expansion plan.

Representing the Ngäbe and Buglé people of western and central Panama, Feliciano Santos of the Movimiento por la Defensa de los Territorios y Ecosistemas de Bocas del Toro (MODETEAB, Movement for the Defense of the Territories and Ecosystems of Bocas del Toro”) said that mining continued to pose a significant threat to Indigenous lands.

“Panama is not implementing collective rights laws and this is leaving thousands of Pndigenous pPeoples in a defenseless position, given the advance of non-Indigenous peoples for extraction activities,” he said. “They have been attacking our lands for these extractive activities.”

In fact, the Panamanian government’s “Atlantic Conquest” development plan includes several new mines in traditional Ngäbe and Buglé lands, as well as a new coastal highway, hydroelectric plants and various tourism projects.

Santos also complained of extremely long procedural delays. For example, communities within so-called “áreas anexas” (areas annexed to the Comarca Ngäbe-Bugle, but not yet legally included within it) have been waiting 19 years for the promised demarcation of their boundaries. Two hydroelectric projects, Chan 75 and Barro Blanco have since been built inside áreas anexas without the free, informed and prior consent of the Indigenous people living there.

Héctor Huertas, a Guna lawyer from the Corporación de Abogados Indígenas de Panamá (CAIP, Indigenous Lawyers Corporation of Panama) criticized the implementation of Collective Lands Law 72 (2008), which provides the framework for collective land titling outside of the Comarca system.

Héctor Huertas Photo: CIDH/flickr (CC)

“One of the first actions of the government was to diminish its legal obligations [and] to adopt decree 223, which regulates law 72 without the participation of Indigenous communities,” said Huertas. “It imposes impossible additional requirements for us to be able to access… [our] lands… [Decree 223] has actually perverted the nature of the law, and it is quite an onerous and bureaucratic process for the Indigenous communities…”

Executive Decree 223 (2010) requires the Environment Ministry to approve Indigenous land titles, which it has not been doing because it says that nationally protected lands cannot be titled. However, Huertas called the pretext false.

“The state says that there are constitutional, legal and international commitments that have prevented them from doing this because they must protect the forests and they are providing false arguments that are discriminatory and have no legal basis,” said Huertas.

“All protective areas in Panama have statutes that recognize the right of property… [and] Inter-American jurisdiction has set the precedent that Indigenous and ancestral possession is the same as a land title, and is compatible with Indigenous property rights in these areas, even though these areas are biological and conservation areas…”

Huertas said that there was no legal provision preventing the recognition of collective land rights in protected areas. He also claimed that the State had shifted responsibility for demarcating Indigenous lands to the Indigenous communities themselves, and that the results were often unsatisfactory to the government.

“Every time a map is presented to the Ministry of Environment or other authorities they say the coordinates are not correct. They look for some excuse,” he told the commission. “Now the ministry… is demanding we submit a digital map…”

In response, the State of Panama objected to the claim that it had delayed the implementation of collective land titling laws.

“The Panamanian state affirms its commitment to protecting human rights in general and to guaranteeing its commitment to collective land rights, to a healthy environment, to access to water, to sources of food and Indigenous traditions,” said Gina López Candanedo, director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

After describing the various legal and administrative measures adopted by the State with respect to Indigenous rights and collective land titling, she concluded: “It is clear that the state has not delayed in implementing [the law]… The government has progressively strengthened its international framework.”

Likewise, Omar Espinoza of the National Geographic Institute insisted that the government was committed to fulfilling its legal obligations towards Panama’s Indigenous Peoples.

“[The State] has centralized Indigenous land titling to speed up the process and to provide greater efficacy for these procedures and to guarantee international standards in favor of the petitioners and Indigenous Peoples,” he said. “The state’s activities aim to strengthen the dialogue with these people and to provide for the territorial integrity of these Indigenous Peoples.”

Jorge Garcia, chief of biodiversity at the Ministry of Environment described the titling process as “interagency in nature”. He said that further technical investigations were being carried out in Darién in accordance with a roadmap agreed during a roundtable mediated by a human rights ombudsman.

However, the IACHR commissioners did not appear to be entirely convinced by the State’s declarations.

Commissioner Antonia Urrejola (left). Photo: CIDH/flickr (CC)

“It is not enough to have mechanisms,” said Antonia Urrejola, the Special Rapporteur for Indigenous Peoples. “It is not enough to have laws recognizing established or statutory mechanisms… for the delimitation and demarcation of lands. It is fundamental that these mechanisms be adequate in keeping with the uses, customs and customary law of the peoples, but above all else that they be effective…”

In addition to questioning the efficacy of the State’s collective titling mechanisms, Urrejola wanted to know if there was a willingness on the part of the state to include Indigenous Peoples in the management of protected areas.

“It is very feasible to establish protected areas under the administration of Indigenous Peoples,” she said.

She also wanted to know if protected areas in Panama could be mined, since the petitioners had indicated that collective land titling was being withheld to provide resources to extractive industries.

Commissioner Flavia Piovesan, the rapporteur for Panama echoed the sentiment that Indigenous stakeholders could feasibly administrate protected areas. She also asked for more details regarding the legal requirements for prior impact studies for development projects.

Commissioner Soledad Garcia Muñoz, the Special Rapporteur on Economic, Social, Cultural and Environmental Rights called the Indigenous Peoples “the great guardians of the land” and asked if there were any special measures to analyze the contributions of Indigenous people in protecting nature. She also asked about the State’s work on business and human rights, and whether legislation was being designed to ensure water security.

Finally, Assistant Executive Secretary Claudia Pulido wanted to know more about the attributes of collective property, and to what extent collective property rights were assured.

The State thanked the commission and committed to answering its questions in a final report, to be submitted at a later date.

Commenting on the hearing, Joshua Lichtenstein, the Rainforest Foundation’s Panama Program Manager told IC that collective titling in Panama was contingent on political will.

“Today Indigenous leaders were able to bring the Government of Panama to the IACHR to answer questions about why the titling of Indigenous collective lands has been stopped by the Ministry of Environment,” he said.

“The government did not have very good answers for that, and in fact admitted there were no real legal barriers. So the problem is political, and constitutes an ongoing serious violation of human rights. The IACHR offered their assistance to the government to help resolve the problem, an offer we hope the government will accept.”

Ostensibly, the government does appear to be willing to find a resolution.

“[The state] will accept any recommendation of the commission in order to protect these extensive [Indigenous] rights,” said Candanedo, before stressing the governments “openness and willingness to continue working with Indigenous people on land titling.”

However, it remains to be seen whether the State of Panama is genuinely committed to Indigenous rights, or whether it is merely paying lip service to its international obligations.

After hearing powerful testimonies from the Indigenous petitioners, the commission pressed the Panamanian State on the efficacy of its collective titling procedures, as well as its apparent reluctance to include Indigenous Peoples in the stewardship of nationally designated protected areas.