By Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois/French)

Elder Dr. Francis Whiskeyjack (Saddle Lake Cree Nation) remembers a childhood filled with darkness. But there were speckles of light too. That light represented his time working alongside Ukrainian farmers during summer breaks. Whiskeyjack is a residential school survivor. He was one of thousands of Indigenous children across Canada who was forced to attend the state-sponsored, church-run assimilative education centers. Thousands of Indigenous children experienced neglect and abuses of all kinds at the schools-some never even made it home alive.

Whiskeyjack got a break from his hell on earth at the Blue Quills Residential School near St. Paul, Alberta when he was first sent to work for a Ukrainian family at age 14.“They were really kind,” he says during a phone interview. “The farmer used to take me under his wing and give me wages at the end of the summer.” Most Indigenous teenagers that were sent to work on farms across the prairies did not get paid for their labour. But the Ukrainian family treated Whiskeyjack fairly and he was proud to earn money to help feed his family back home on the reserve. “I remember one time, I worked all summer and he gave me a big fat sow! It got made into bacon and meat. They always had great big gardens and they’d give me carrots, beets, corn, all kinds of vegetables to bring home.”

Elder Dr. Francis Whiskeyjack smudging. Photo courtesy City of Edmonton.

He was taught agricultural skills like hay baling and how to drive and maintain farm equipment. And he was fed well there.

Whiskeyjack says he especially liked the Ukrainian food: perogies; sausages; and cabbage rolls. Even after several summers of working for Ukrainian farmers, Whiskeyjack says he encountered other Ukrainian people when he became employed at a local power plant. They always treated him as a “brother,” he says, which is a stark contrast to what he was used to from French settlers in the area who looked down upon him because he was Indigenous.

“There was a good relationship. I didn’t find that the Ukrainians in our area were ever [racist], I’d never experienced any kind of racism [from them.] I think they understood what it felt like to be considered inferior to other races. They saw the Native people. They had compassion, and they maintained the dignity of our nation. Whereas if I went to St. Paul, I remember that very specifically, the French had a distaste and were racist towards Native people.”

When Whiskeyjack learned of the Russian invasion of Ukraine he immediately felt concerned for the Ukrainian people. He’s been praying for those in the line of fire and says several nearby First Nations communities are conducting sweat lodge ceremonies for Ukraine. “I already know what it's like to be treated so unfairly and it's [the war] like colonialism all over again, somebody that's domineering and trying to take over your identity or country. And as a humanitarian, I feel that it's another Holocaust.”

Cheryl Whiskeyjack (Anishinaabe), a distant relative of Francis, married into the Saddle Lake Cree Nation. She’s been praying for the welfare of the Ukrainian people too. “I feel I'm all over the place,” she says via telephone. “Like, I can't even imagine. We’ve had a lot of bad things happen [First Nations] but how horrifying this is for them.”

Cheryl Whiskeyjack and niece Infinity Rahko-Pitawanakwat wearing a kohkum scarf. Photo courtesty of Cheryl Whiskeyjack.

Several days ago, she hung a “kohkum” scarf outside her front door in solidarity with Ukraine. The colourful flowered scarves that have become popular in Indigenous culture originated in Ukraine. Since the war started many Indigenous women from across Turtle Island are snapping selfies with the scarfs and posting photos in solidarity with Ukraine. It’s said that settler Ukrainian women gifted the scarfs to native women at the turn of the century as a symbol of friendship. Cheryl first learned of the connection of kohkum scarfs to Ukrainian women a few years ago at a powwow.

“I told someone wearing a kohkum scarf that she looked like one of the Ukrainian women from a long time ago. And then that's when this old lady who was sitting by me said that's where it comes from. And I'm like, wow, really?” Her young niece incorporates a kohkum scarf into her pow wow regalia and wears it with admiration. “So, that story of the kohkum scarf for me was another opportunity to show that we've been here together for a long time. We can be together in a good way.”

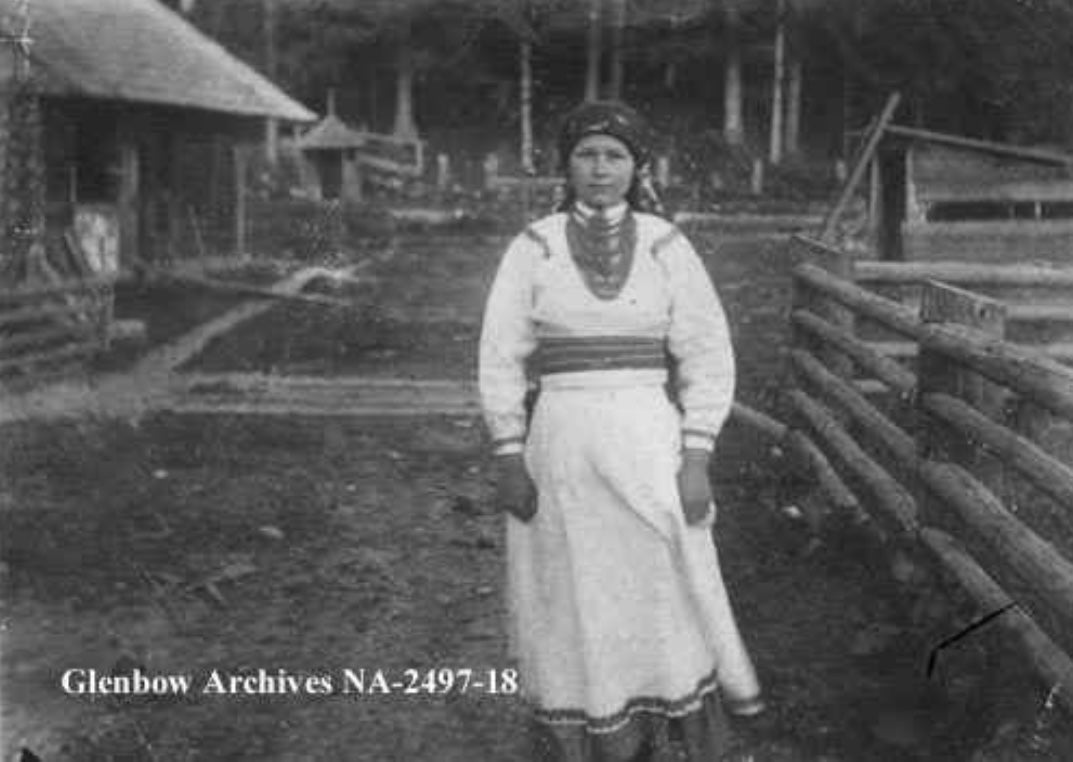

Sophie Hrynchuck, Ukrainian settler wearing kohkum scarf. Redwater Alberta,1912. Photo courtesy of Glenbow Museum.

Cheryl learned more about Ukrainian culture several years ago while visiting the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village, an open-air museum that uses costumed historical interpreters to recreate pioneer settlements in east central Alberta. She learned from a Ukrainian interpreter there just how strongly tied the First Nations and Ukrainian settlers once were. “He said, 'we were very allied to one another very early. When people came from Ukraine,'" she explains, " 'Ukrainian people were ranked with Indigenous Peoples on the hierarchy [of society].' So he said they were treated very terribly and were seen as outsiders and very foreign in their ways. The Canadian society just wanted them to come here and assimilate. They didn't want them to retain their culture. They were sent to a school and they were severely punished for using their language and for observing any of their ways.”

Canada has the second-highest number of Ukrainian people in the world next to Russia at 1.4 million. Thousands of Ukrainian settlers immigrated to Canada starting in the late 1890s to farm the western prairies and beyond. Including Toronto where Harmony Redsky’s (Anishinaabe and Ukrainian) Ukrainian grandfather settled after WWII.

Harmony Redsky's daughter Nadia Rice-Monastyrski in Ukrainian dance dress. Photo courtesy of Harmony Redsky.

Redsky and her family have been paying close attention to the tensions rising between Ukraine and Russia for the last several months. But the day Russia invaded Ukraine Redsky and her family went into high gear trying to track down their family members living in and close to the capital city of Kyiv. “The communications have been cut,” says a flustered Redsky in a telephone interview from her home east of Winnipeg, Manitoba. “There’s no internet. We don’t know who has been evacuated. We have about 40 family members living there.”

Redsky thought of her beloved grandfather Stefan Zyganiuk, a WWII veteran. He met and fell in love with her Anishinaabe grandmother Jean while she was working in kitchens on steamships on the Great Lakes. Theirs was a romance of overcoming the obstacles of two different cultures and two languages. The couple married and set up a home in Toronto where they raised four children together. Zyganiuk taught his First Nations wife how to make Ukrainian dishes like perogies, cabbage rolls, and borsch. He taught his children and grandchildren his Ukrainian culture and shared the legends of his homelands. He kept in touch with his family in Ukraine and sent regular care packages filled with Canadian treats and First Nations mementos. Jean also taught her children and grandchildren her Indigenous language and culture. “They instilled both cultures in us kids. He always said to us that he was Anishinaabe. I interpreted that to mean that our culture was so similar-in dance, song, spirituality, and connection to nature,” recalls Redsky.

Harmony Redsky and her grandfather Stefan and her daughter Nadia Rice-Monastyrski. Photo courtesy of Harmony Redsky.

Her grandfather, who passed away in 2013 at the age of 97, used to take Redsky on walks through the forest and teach her to weave baskets from the fibers of the trees, something he learned back home. And Redsky remembers the scarves from her childhood. They were given to her by her grandfather and used in ceremonies of her home community of Wasauksing First Nation. “It’s good that the history is getting out there and people realize the connections we have through the scarves.”

Zyganiuk was a proud veteran, says Redsky, who was also fiercely proud of his Ukrainian identity. “So, I thought about what would grandpa do [right now]? I feel that he went to his family [in Ukraine] immediately and has been watching over them. And I know he’d want us to help him and be a support.” She and her family check their email daily for a response from relatives in Ukraine. She’s even been looking at refugee lists in Poland but hasn’t yet found her family. She describes watching the war unfold as “surreal.” “I’m going through my workday and it’s hitting me. This is life and death.”

Meanwhile, back in Alberta, Darka Tarnawsky, Executive Director of Ukrainian Shumka Dancers in Edmonton struggles to grapple with the violence unfolding in Ukraine. She’s comforted, however, by the outpouring of support shown by community members and the Indigenous community. “It warms our hearts and is helping to bring people together in a time of tragedy,” she told Cultural Survival via telephone. “We've just been overwhelmed by that show of love.”

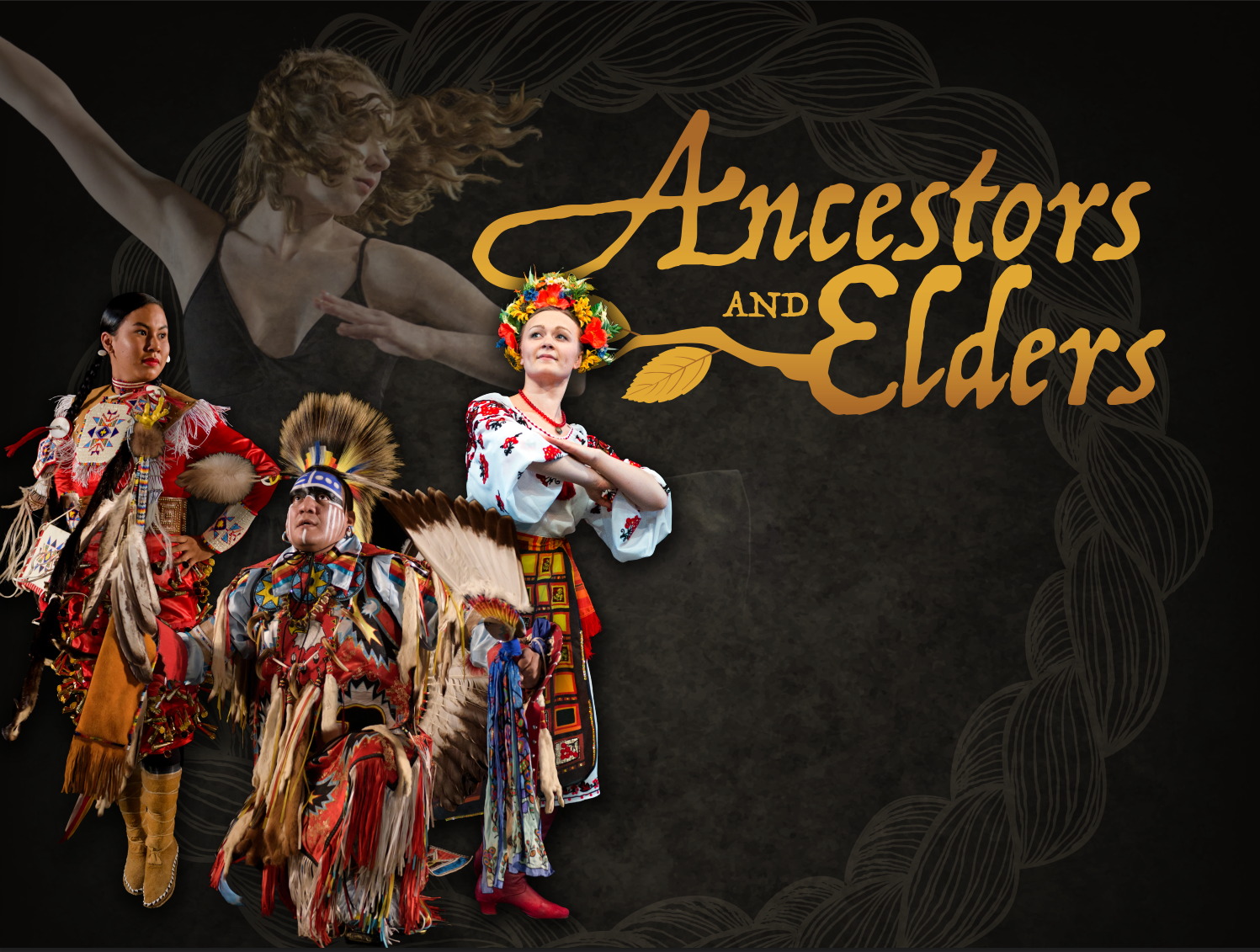

Ukrainian Shumka dancer and a First Nations Elder dancer. Photo courtesy of Ukrainian Shumka Dancers in Edmonton.

She knows about the local history between Ukrainian settlers and Indigenous Peoples in Alberta. It was a relationship of reciprocity, the way the relationship between the newcomers and First Nations was intended to be. But as we know, not everyone held up their Treaty obligations. The First Nations welcomed the Ukrainian settlers and taught them how to survive in harsh, barren winters.

A Ukrainian family harvesting on the prairies. 1918. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives of Canada.

Tarnawsky helped bring to life Ancestors and Elders in 2019, a dance production in partnership with the Running Thunder Dancers featuring over 100 dancers of Ukrainian and Indigenous backgrounds. The show told a story of these two cultures meeting, the friendships created, the tragedies of the attempted erasure of Indigenous culture by mainstream society, resilience and reconciliation. Shumka describes the relationship portrayed in the production as, “Survival, for both Indigenous and Ukrainian immigrant people in Alberta, often meant silence: lost stories and connections between our communities help us all survive tremendous loss and struggle. We use dance to begin to break that silence; to remember those who came before us, the traditions they instilled, and the truths they endured.”

“At the turn of the century and how they [Ukrainian settlers] were helped by the Indigenous community was just such a beautiful story to us. And we knew that most people didn't know about that. Now, there's been something that's really coming out lately [from the Indigenous community] with the whole situation in Ukraine, there's been a real outpouring of love and support,” says Tarnawsky.

Adrian LaChance (Cree), a powwow dancer and founder of Running Thunder Dancers served as artistic director for Ancestors and Elders. He says he experienced a lot of emotions throughout the production. “We [First Nations] got ripped apart,” he reflects during a phone interview. “Our culture was outlawed. It was creating that through dance and imagery but celebrating too. Because we, like the Ukrainians, are about never giving up, celebrating life and including people.”

Ukrainian Shumka Dancers featuring Adrian LaChance. Photo courtesy of Ukrainian Shumka Dancers.

He says the young Ukrainian dancers were eager to learn about First Nations cultures and dancing. He noted the similarities between his culture and Ukrainian culture via the incorporation of colours in costume and regalia and connections to the land. The group often smudged and prayed together during rehearsals and before shows. Since the war began, he’s been working to help the local Ukrainian community and will participate in a fundraiser to be held on March 13 in Edmonton.

The chief of the Enoch Cree Nation west of Edmonton shared a message of support to Ukraine highlighting the friendships between Indigenous and Ukrainian Peoples via social media. The post went viral. Chief Billy Morin says he’s been constantly scanning news updates regarding the war in Ukraine and sending his prayers there. The connections, he says, go deeper than friendships. “It seems like every local First Nation had at least some direct ties [to Ukrainians] and that was more than friendship. It was family,” he says.

Chief Billy Morin and his Principal Advisor, Jordan Turko who is of Ukrainian decent. Photo courtesy Chief Billy Morin.

“So you kind of feel a direct connection to that, to what's going on. I think Ukrainian and First Nations people have been through a lot and they're kind of united in the fact that they both experienced genocide, but for over 100 years in multiple locations. So, it just personally kind of hit me hard.”

He went on to share how he’s been told multiple stories of Ukrainian settlers needing Indigenous Peoples for survival. How the relationships were based on sharing culture, songs, and food. He believes Indian Country is showing massive support for Ukraine because of the will to survive the violence of oppression. “Our people are fighting that fight here locally, every individual, First Nations. And that sovereignty aspect of things and we see Ukraine growing through this in the most brutally savage way…There's a lot of polarization in the world right now. And I think it goes back to simplicity, which is, people come together when times are tough. So let's put down our differences and figure out what ways we can work together.”

--Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois/French) is an award-winning journalist reporting on human rights issues from an Indigenous perspective. Her debut memoir, “Our Voice of Fire: A Memoir of a Warrior Rising,” is out this summer.