On the morning of August 8, 1984, seven elder men in the Xavante community of Etéñhiritpa, known as Pimentel Barbosa in Portuguese, slipped quietly from their houses. Each followed the path that passes behind the arc of beehive-shaped houses, discretely making their way to the marã, a secluded forest clearing used for ritual preparations. The night before, Warodi had told me that the celebration would take place today. As we sipped the precious coffee that I had brought to Pimentel Barbosa, I eagerly awaited some sign that preparatory activities had begun. Rising from his seat near the cookfire and preparing to go, Warodi beckoned me to follow.

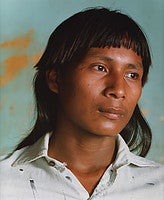

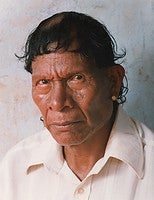

Warodi was the eldest son of the formidable leader Apöwê, the man responsible for the Xavante’s first peaceful contacts with representatives of Brazilian national society in 1946. In the late 1970s Warodi led the Xavante of Pimentel Barbosa in an impressive battle to reclaim lands that had been illegally swept from their jurisdiction. As the community’s representative, he made multiple arduous trips to the capital, Brasília, to negotiate with officials of the government Indian agency, Fundação Nacional do Indio (FUNAI). When these negotiations proved futile, the Xavante of Pimentel Barbosa attacked and burned ranches in the area. Warodi then summoned representatives and leaders from the other Xavante reserves; together these men cut down a line of trees through a forested area to demarcate the reserve’s contested border according to Xavante claims. That gathering constituted the first politically coordinated action of the different Xavante reserves and cemented Warodi’s reputation as a bold political actor. William Crawford traveled to Pimentel Barbosa with Cultural Survival founders David and Pia Maybury-Lewis in 1982, two years before Warodi shared the dream recorded by Laura Graham. This portrait is among the photographs he took on that trip. Photo by William Crawford.Warodi also had a magnificent knowledge of Xavante history and the past; his speech resonated with information about the creation of the world. For example, when he and his brother Sibupa (whose photograph is on this issue’s cover) discussed government plans to asphalt the road that runs next to the reserve’s western border, Warodi spoke of the ways this project fit into the first creators’ work. One of his nephews aptly characterized him as “one whose head seems always to be with the creators, the höimana’u’ö [always living] ancestors.”

William Crawford traveled to Pimentel Barbosa with Cultural Survival founders David and Pia Maybury-Lewis in 1982, two years before Warodi shared the dream recorded by Laura Graham. This portrait is among the photographs he took on that trip. Photo by William Crawford.Warodi also had a magnificent knowledge of Xavante history and the past; his speech resonated with information about the creation of the world. For example, when he and his brother Sibupa (whose photograph is on this issue’s cover) discussed government plans to asphalt the road that runs next to the reserve’s western border, Warodi spoke of the ways this project fit into the first creators’ work. One of his nephews aptly characterized him as “one whose head seems always to be with the creators, the höimana’u’ö [always living] ancestors.”

The other men that morning—Sibupa, Wadza’e, Eduardo, Raimundo, Daru, Ai’rere, the Etêpa—had seated themselves in a circle around the coals of a small fire whose glow took the chill off the Central Brazilian Plateau’s crisp morning air. As the sun’s rays crested over the trees, Warodi took his place among the elders. The gathering was small: it was the dry season, when a number of families were off on trek, the extended hunting trips typical of the traditional Xavante seminomadic lifestyle. Because no major celebration, such as the male initiation ceremonies or the ceremonials of the wai’a, were scheduled this year, the trekking groups would not return until sometime in September. Nevertheless, among those present were some of the community’s eldest and most committed leaders of ceremonial life. These eight men talked quietly among themselves, paying no attention to the adolescent novitiates who worked nearby clearing brush to enlarge the forest opening.

The soft murmur of their conversation blended into the sounds of the waking forest. From time to time loud birdcalls punctuated the cicadas’ buzzing drone. Suddenly Warodi cleared his throat loudly, spat, and began singing very quietly. His singing was at first almost imperceptible. As he repeated the song’s patterned phrases, the others joined in, also with hushed voices. There was a moment’s silence when the song finished. Only the sound of the novitiates rustling in the brush and the early morning birdcalls disturbed the calm. After a brief pause Warodi recommenced his singing, this time at full volume. As the others joined him, their deep, mature voices resounded in the forest clearing. When they stopped, Warodi whispered, “This is öwawẽ-’wa’s [the one who created the seas]. It is his.” He then went on to sing two more songs, at first softly, then once again loudly after the others joined him. When the elders had learned the three songs according to his pattern, Warodi led them through the entire set, singing at full volume. In this way Warodi taught the others the songs he had learned in a dream.

After a brief pause Warodi recommenced his singing, this time at full volume. As the others joined him, their deep, mature voices resounded in the forest clearing. When they stopped, Warodi whispered, “This is öwawẽ-’wa’s [the one who created the seas]. It is his.” He then went on to sing two more songs, at first softly, then once again loudly after the others joined him. When the elders had learned the three songs according to his pattern, Warodi led them through the entire set, singing at full volume. In this way Warodi taught the others the songs he had learned in a dream.

Immediately after finishing the third song, Warodi began to speak, very quietly. From time to time others added their voices; frequently several elders spoke at the same time. Punctuated with clicks and emphatic glottal sounds, their simultaneous utterances, their staggered and overlapping phrases produced a soft but acoustically spectacular murmur in the forest clearing. It was difficult for me to make out what Warodi was saying; his voice was barely audible even without the constant voice-over contributions of his neighbors.

Echoed by affirmations, questions, asides, and comments, Warodi recounted his dream to the elders. In his dream, Warodi participated in a gathering of immortals. Among those present were the ancestors responsible for the Xavante creation: the two parinai’a, boys who had created animals, insects, fish, and foods; the wedehu date da-wa’re (the one whose foot was pierced by a stick), who augmented the Xavante population; and the boy whose stomach burst, the öwawẽ-’wa, who created the sea and the whites. These creators, Warodi reported, had given him their songs as gifts to the living, so that, performing them, the Xavante would continue as Xavante forever.

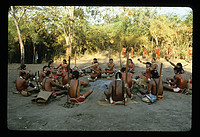

Thus began a unique celebration that was itself a performance of Warodi’s dream. That morning Warodi sat among the elders of Pimentel Barbosa as he had sat among the ancestors of his dream. He taught the creators’ songs and shared their thoughts with the living in the same way that, in the dream, the creators had shared their thoughts with him. As Warodi recounted his vision, he and the others made plans for the dream performance, a performance that would include the entire community. These plans merged into Warodi’s dream narrative, blurring the distinction between the present and the time of the mythic creators who had appeared to Warodi. Down to the last detail the elders designed their celebration to represent the dream activities as Warodi reported them. They discussed their body paint, for example, as the ancestors had done. They chose designs to replicate those that the immortals wore in the dream. With these designs, as Warodi’s brother Sibupa pointed out, the performers would be the immortals themselves.  Senior men sit in the forest clearing practicing singing as the elders did when Warodi recounted his dream. Photo by Laura R. Graham.The elders then summoned three of the community’s young men. With body paint and buriti palm fiber robes they transformed the three into the creator figures who had appeared in Warodi’s dream as birds. Two of the young men represented the parinai’a creators. The elders blackened their eyes with charcoal, then encircled them with red urucum. With painted eyes, woven fiber robes, and headdresses, these two appeared as jabiru storks. This form, of all the transformations that the parinai’a underwent when making the creation, is the one Xavante associate with the creators’ incarnation in the present time (parinai’a is the name of a wasp’s nest, one of the creators’ metamorphoses). To the oiled body of the third young man the elders applied just a bit of red paint, making him appear as the creator he represented. Outfitted in a palm-fiber robe, he too appeared in the form of a bird, as Warodi had envisioned him in his dream.

Senior men sit in the forest clearing practicing singing as the elders did when Warodi recounted his dream. Photo by Laura R. Graham.The elders then summoned three of the community’s young men. With body paint and buriti palm fiber robes they transformed the three into the creator figures who had appeared in Warodi’s dream as birds. Two of the young men represented the parinai’a creators. The elders blackened their eyes with charcoal, then encircled them with red urucum. With painted eyes, woven fiber robes, and headdresses, these two appeared as jabiru storks. This form, of all the transformations that the parinai’a underwent when making the creation, is the one Xavante associate with the creators’ incarnation in the present time (parinai’a is the name of a wasp’s nest, one of the creators’ metamorphoses). To the oiled body of the third young man the elders applied just a bit of red paint, making him appear as the creator he represented. Outfitted in a palm-fiber robe, he too appeared in the form of a bird, as Warodi had envisioned him in his dream.

When the creators were ready and the men, having completed their preparations, were well appointed with body paint, they summoned the women to join them. Once all the members of the community assembled, Warodi led them through a rehearsal of his dreamed songs. Again he recounted his dream and prescribed their body paint so that their designs would conform to his vision and bring the voices and embodied images of the immortals and creators into the world of the living.

At 4:00 PM, when the preparations were complete, the community moved into the central plaza. In their bird costumes, the creator figures stood in the center of a large circle of dancers. Following Warodi’s lead, the people joined hands to sing and dance the three songs. As they sang and danced, the creator figures moved their arms in imitation of storks flapping their wings in flight. In performance the participants became the immortals of the dream. The performance crystallized the transformation that had been budding through various expressive practices rehearsed during the long day. The past merged with the present and the immortals lived through the actions of the living. Through their singing and dancing, the living brought the immortals into the present, into the realm of the living.

This article is adapted from Performing Dreams: Discourses of Immortality Among the Xavante of Central Brazil, by Laura Graham, published by Fenestra Books (2003, originally published in 1995 University of Texas Press). Laura Graham has carried out ethnographic and advocacy work among the Xavante since 1982. She is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iowa and also serves on the board of Cultural Survival.