At Filene's department store in Boston, you can buy a purse fashioned from Zapotec wool textiles. You can also buy rugs, wall hangings, pillows, and seat covers made by the Zapotec in southern Mexico. Indeed, in southern Mexico. Indeed, the United States is a society of handicraft consumers, but who produces the crafts? How do our purchases influence faraway lives?

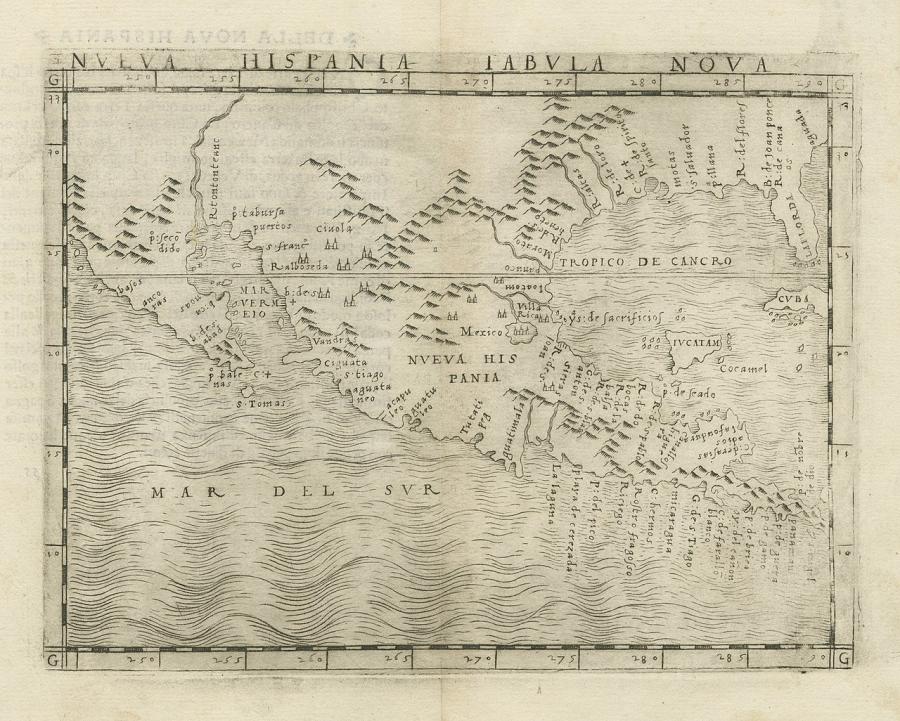

The Zapotec of the village of Teotitl n have long been famous for textiles. Before Spaniards arrived, Teotitl n paid tribute to Aztec emperors with cotton mantles. The introduction of sheep and the stand-up treadle loom by the Spaniards set the scene for making wool textiles, and from the colonial period into the 1950s, the Zapotec of Teotitl n produced quality wool blankets and ponchos for sale in Indian markets of Oaxaca.

Beginning in the 1950s, when the Pan American Highway brought tourists to Oaxaca, foreigners began showing an interest in Zapotec tectiles. The advent of polyester blankets, and the resulting collapse of Mexico's traditional weaving industry, meant that the tourist market and, eventually, exports provided a crucial niche for Zapotec weavings.

Today, Teotitl n is booming, and its 5,000 people earn most of their income from weaving. The community boasts a new market building and a yarn factory built in the mid-1980s, plus a new school, six doctors, a dentist, and two pharmacies. While once a town of farmers and part-time weavers, about half the people now have no land; instead, craft production is the axis of the economy.

Zapotec, one of 52 indigenous language in Mexico, remains the main mode of communication. Most people under the age of 30 are bilingual, but most older women and some older men speak only Zapotec. Yet success has significantly changed the work that women do. Changes appear not only in textile production, but in many other aspects of daily life.

Until the 1970s, men did most of the weaving, and it was rarely a family's sole support. Subsistence farming also contributed to household finances. Since the 1970s, many homes have come to depend on weaving, and women and girls increasingly are the weavers. This responsibility comes in addition to, not instead of, traditional domestic chores: caring for animals and children, preparing food, handling ceremonial obligations, and assisting with farming.

THE GENDERED DIVISION OF LABOR

Tourists and exporters want not just any wool textile; rather, they seek indigenous handmade crafts. The handmade aspect means that labor is a central component of production. In the case of the Zapotec, as the market expanded, more hands had to be found to produce the weavings. Men from other villages could have woven more rugs and blankets, but instead the work of women and girls expanded to include weaving on a wide scale for the first time.

Actually, some Teotitl n women had practiced the craft in the past. For example, when many men left for migrant work in the United States during World War II, some women took on their weaving. It was one of the few ways to earn money while waiting for husbands, fathers, and brothers to return with wages from the United States.

Since the 1970, learning to weaves has been part of every young girl's education. Girls begin by weaving 12-inch by 12-inch squares when they are as young as eight years old. They graduate to larger pieces as they can fit better in the stand-up treadle looms introduced by the Spanish. The labor of teen-age women is a very important source of income in many homes.

Many young women leave their homes between the ages of 15 and 18 to live with a spouse's family, migrate to other parts of Mexico, or head to the United States. Many who go to the United States end up cleaning houses or caring for children in Los Angeles. Imelda Ridriguez, now 31 and back in Teotitl n, describes one of her first Los Angeles jobs 17 years earlier:

My aunt got me a job working in a house taking care of a little girl. They were people who came from Texas. I didn't understand any English - nothing, nothing. They only spoke English. They spoke to me and I answered them in Spanish. For the three months I worked there, I only ate liver because I didn't know how to ask for any other food. The only thing the man of the house knew how to say in Spanish was "Liver? Liver?" So I said, "OK, liver."

Those who marry and remain in Teotitl n move to their in-laws' homes, and the birth of children usually means a tremendous work load. Many young women continue to weave while caring for babies, preparing food, raising animals, and helping with farming. While most women continue weaving for the income, many complain of exhaustion, back pains, and other physical ailments. "When you get married you feel the strain of weaving." says Josefina Vasquez. "With the first child, a lot of women who weave feel a lot of pain because the loom mistreats your belly. It is hard to stand up for so long. Then later you have a child to take care of as well. No one helps with the children."

Young mothers weave with babies strapped to their backs in shawls. However, as children, particularly daughters, get older, they help around the house. For the reason, Zapotec women often welcome several daughters. A crop of sons means they will get little relief from domestic and weaving chores until one of them brings home a bride.

ORGANIZING RITUALS

As commercial weaving, and women's importance in it, grow, women's time for other economic endeavors declines. The impact is appearing on a major responsibility of the Zapotec women of Teotitl n: local rituals that involve extensive exchanges of products and work among households.

Elaborate fiestas mark major Zapotec occasions - weddings, funerals, housewarmings, even birthdays. Often requiring food for up to 200 for days at a time, many of these secular occasions borrow elements from the religious traditions or religious cult celebrations of the local pantheon of saints and virgins. At such times, now confined to two per year instead of the original twenty, a household sponsors a celebration for a saint or virgin and hosts a series of fiestas.

For such events, where religious or secular, a woman's duties can last for months. First of all, large fiestas require her to recruit and coordinate women to help. Making hot chocolate, rice, beans, bread, tortillas, the corn drink tejate, and meals for hundreds of people is no small feat. "Women don't really like to go to fiestas that much because it is a lot of work," explains Cristina Martínez. "Tejate is the worst. You have to grind your arms off. Tortillas are bad because of the heat. Making them makes my arms hurt and my knees sore."

Bonds of kinship and ritual kinship - compadrazgo - are critical to such large events, and the concept of family is broad in Teotitl n. If a woman plans a wedding for a daughter or son, she will call on all the women in her biological family and her husband's family, plus the mothers of all the children - five or more - to whom she is a godmother. Only with these women as a team can she prepare enough food for the event. In return, each of the women can call on her in the future. This reciprocal labor exchange is known as guelaguetza. Reciprocal exchanges also include the rice, beans, corn, chocolate, pigs, turkeys, chickens, and pigs for ceremonies.

By and large, women control the reciprocal exchange of both goods and labor. "Sometimes men don't know what is needed for guelaguetza exchanges," Ana Gonz lez says. "They don't plan the food the way we do. We know exactly what is needed for big meals."

The Zapotec are extremely organized about reciprocal exchanges. Each household keeps a guelaguetza book to record loans to other households, as well as items they have borrowed - a sort of checkbook of goods instead of money. If a household loans a turkey, it can later recall a turkey. Plating debts with other people is a way to prepare for future events. Women will plan years in advance what they will need when their children marry. A women may raise many turkeys, loan them out, and then call the loans in when her son marries.

Guelaguetza used to be a major way to finance rituals and a significant economic institution under the control of women. With the commercialization of weaving and the influx of cash, guelaguetza is less important, particularly for well-off households.

CLASS AND GENDER

The Zapotec women of Teotitl n continue to share an identity through the Zapotec language, their unique history as weavers, and their intense ritual life. Yet at the same time inequality has come to mark Teotitl n. That not all women have the same experience is due not only to differing ages and personalities, but also to class.

One way to understand class in Teotitl n is to look at who works and who employs. The women in about 80 percent of the households weaves for others. In effect, these are the employees, either directly or indirectly, of what can be called merchant households. Merchant households - 10 percent of the households in Teotitl n - contract with weaver households earn about seven times what weaver households earn.

Women's experiences in the two kinds of households contrast sharply. Men alone manage business finances in 67 percent of the 50 merchant households that I have surveyed. Only 4 percent of business finances are managed by women alone, and 29 percent by men and women together. In other words, few merchant women make business decisions. Angela Suarez realizes her lack of control in the family business:

My husband tells me how much yarn to dye, how many weavers we will hire, and what to cook for them for lunch. I also have to buy what he asks me to for the house. He gives me a certain amount of money every day for food. He keeps the key to the money and doesn't let me handle it. He says that he knows how to take care of the money.

For Saurez, this marks a great change from her childhood: "In my parents' and my grandparents' house, after my father or grandfather would sell a weaving they would give the money to my mother or grandmother."

Weaver households have no business finances, just a household pool of money. Men and women manage this money together in 62 of the 100 weaver households I have surveyed. In 35 households, women manage the money, and in only 3 do men manage the money. This translates into more egalitarian decision-making. In addition, many weaver women make production decisions with their husbands, often overseeing the weaving while the man works in the fields.

During community rituals, merchant and weaver women still have much in common. Regardless of class, women decide about household labor and income for fiestas. Yet subtle divisions can appear even around these celebrations. While older age was once associated with the sponsorship of many fiestas and translated into greater respect, this is no longer always the case. Wealth makes merchant families popular as godparents - the richest merchant household in Teotitl n has 246 goldchildren. Young merchant women with many godchildren receive a sort of short cut to a higher social position.

A DIRECT CONNECTION TO BOSTON

While differentiated by class and age, ethnic identity encountered though a shared culture is a glue that lets most women in Teotitl n understand most of each other's lives. But what will the future bring? Will class divisions eventually result in such contrasting lifestyles that weaver and merchant women have little in common? Will the ability of more merchant households to hire servants alter their relationships with other women? What will become of the increasing numbers of young women who leave for Mexico City and Los Angeles? In selling textiles, are the Zapotec marketing their cultural identity as well?

Like most indigenous communities in Mexico, Teotitl n is in transition. While local prosperity lets people stay in Teotitl n and supports costly cultural institutions, the community is not an unadulterated bastion of tradition. Young people are leaving to work abroad, and a few young men attend the university and become doctors or lawyers.

As they become more educated and bilingual, young women, primarily from merchant households, are also beginning to demand education and a voice in community and household decisions. And some women demand their rights in the local political system. In 1989, young merchant women organized and pressured the all-male local government to let them serve on the committee regulating their textile market. Older women used kin networks to boycott a state-run yarn factory. And women played an active role in political attacks on the factory during the late 1980. Since 1991, it has been community-run and supervised by a citizen's committee, although all committee members are men.

Clearly, the economic motor of textile production for export gives people in Teotitl n some economic and cultural choices - rare for Mexico's indigenous people. Nevertheless, much of the economy and the ritual system depend on a U.S. market for Zapotec textiles. As long as U.S. consumers pay from $50 to $1,000 for Zapotec textiles, life in Teotitl n can continue as a happy mixture of past and present, but if the United States continues to suffer a recession, the crafts market could dry up. The weaving labor of most women may no longer be needed, and women's lives will alter once again as household income falls and women contribute less to household income through weaving.

Such outcomes are not certain. What is certain is that the life of a Boston woman who buys a Zapotec textile handbag is directly connected to the young Zapotec woman who rose at 4 a.m. to stand in a loom in Teotitl n.

Article copyright Cultural Survival, Inc.