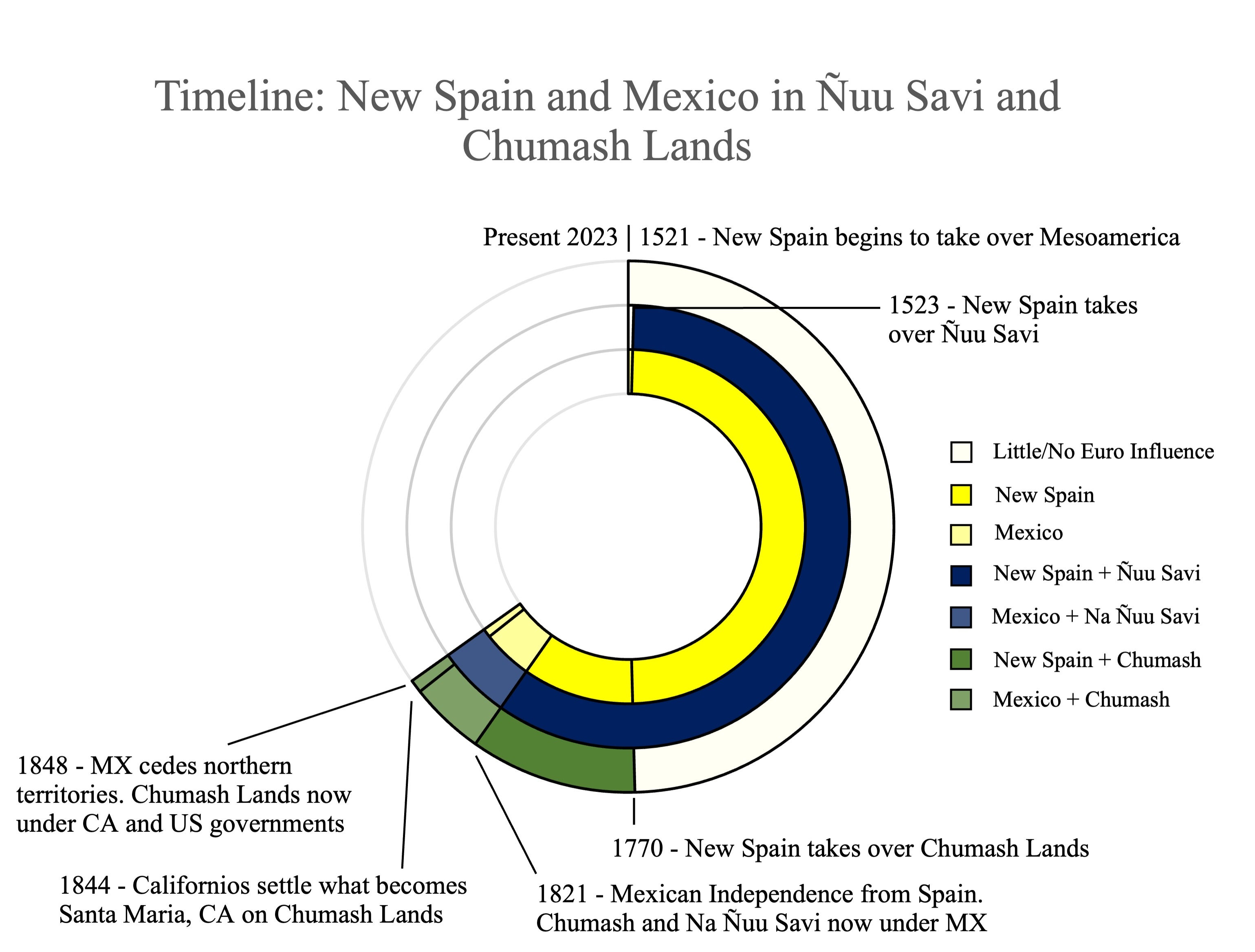

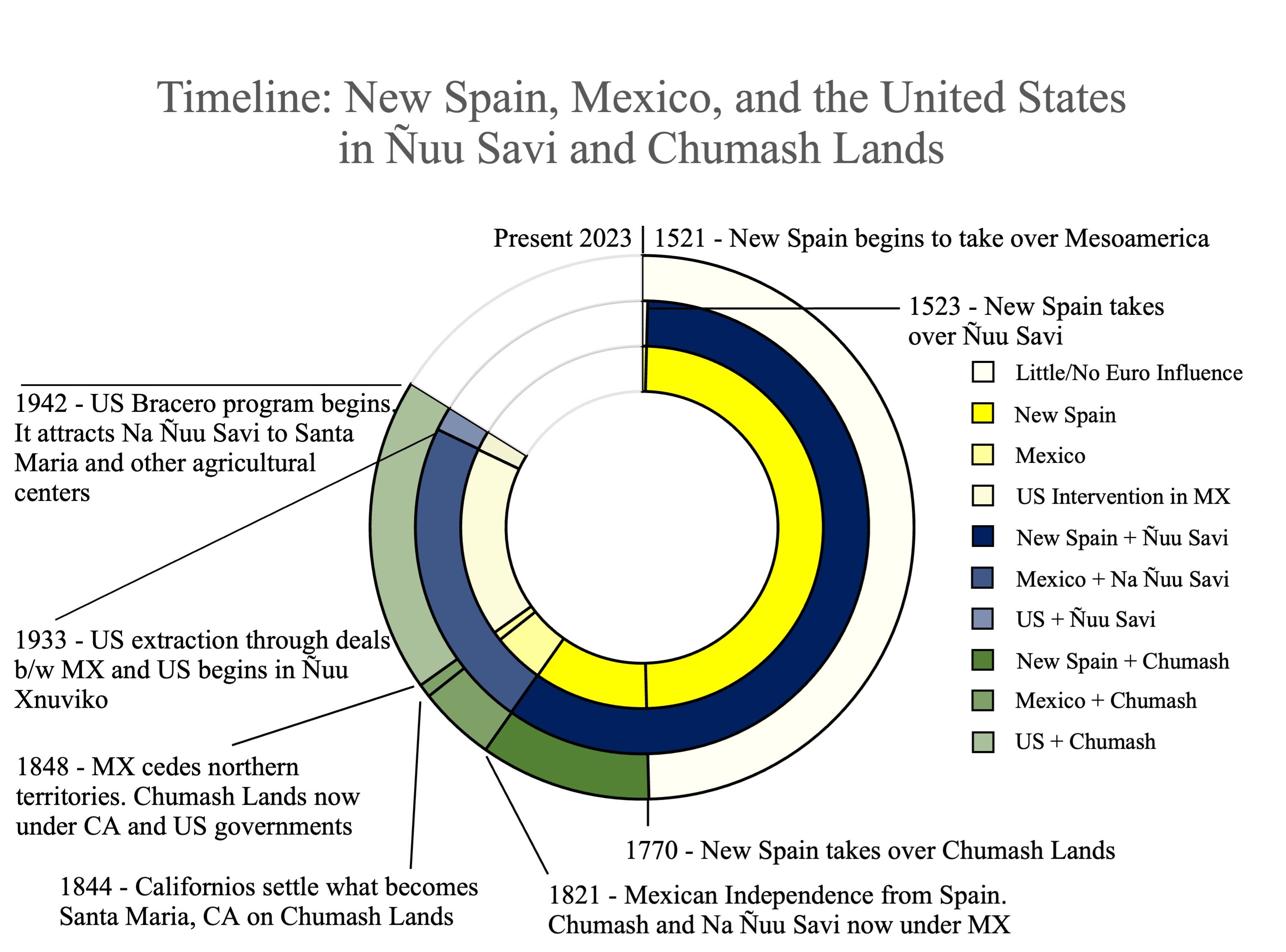

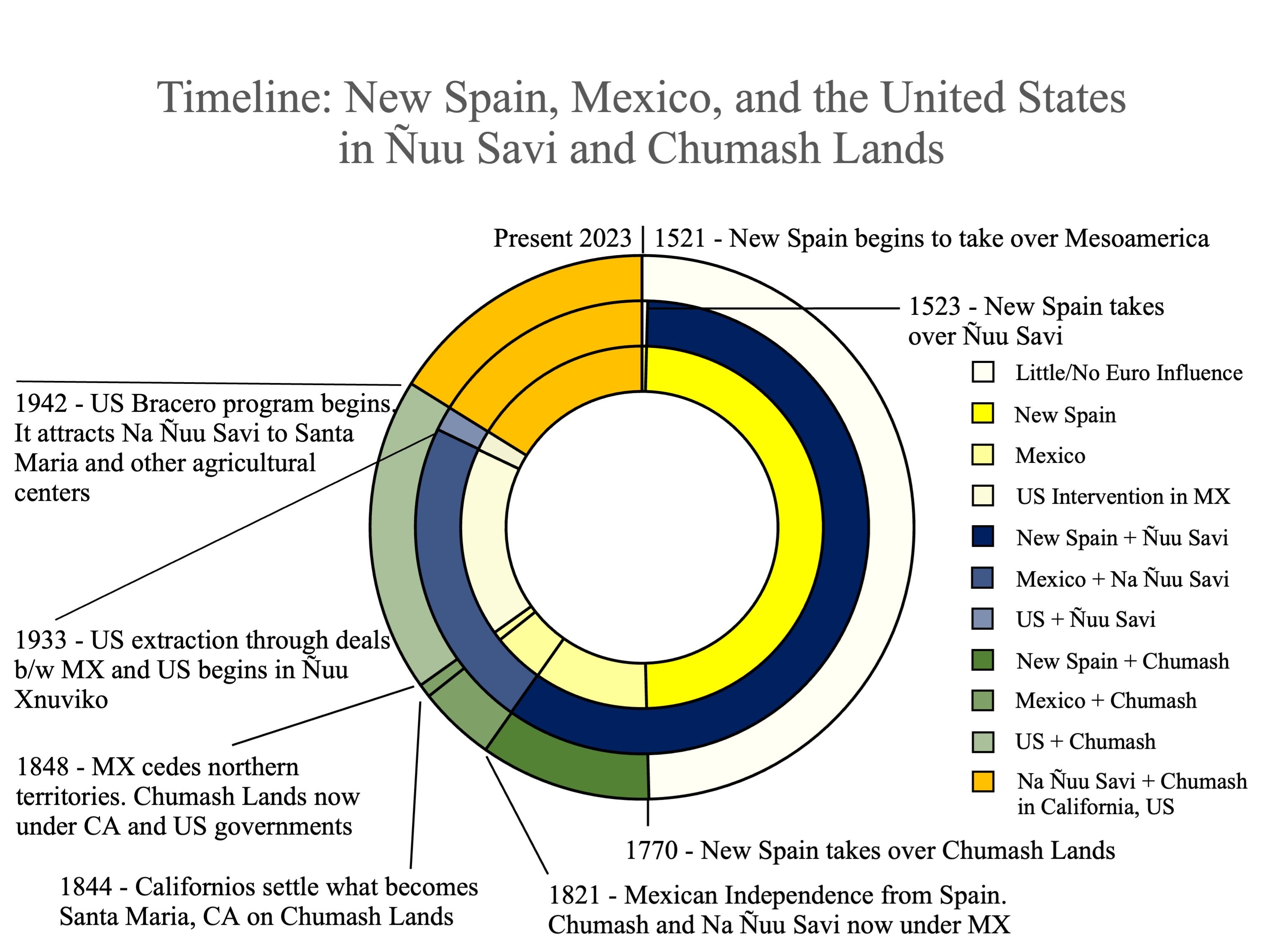

This is a reflection on the shared history between Na Ñuu Savi (Peoples of the Region of the Rain) and Chumash since the origin of their respective homelands in what are now Mexico and the United States. Santa Maria is an agricultural city located in northern Santa Barbara County on the Central Coast of California. It is the second home of Na Ñuu Savi migrants from Yucha Nchaa (Santa Cruz Mixtepec) in the municipality of Ñuu Xnuviko (San Juan Mixtepec), Oaxaca. Between the Santa Marian earth and sky is a backstrap loom on which the history of people in this space is woven. The first shapes formed on this loom are Chumash, people who came from islands and established varying groups on the now Californian coast. The next people are woven into this space through the force of Spanish and Catholic seizure of Indigenous lands, then through the birth and growth of Mexico, through what the settlers of the United States call manifest destiny, and finally through the migrational currents that eventually carried Na Ñuu Savi from their ancestral space to ancestral Chumash territory. This reflection is not an accurate representation of Chumash and Na Ñuu Savi history given the generic use of source material used to date and describes these histories, rather this reflection is meant to sketch the shared colonial influences and their legacies on those communities and estimate time frames related to them.

Read Part I : Legacies of Colonialism and Indigenous Resistance: Chumash and Na Ñuu Savi in Santa Maria, CA

Post-Independence Mexico (1821 - 1848)

Following Mexican Independence in 1821, lands that were previously owned by Dominican churches in Ñuu Savi and Franciscan missions in Chumash territories became government properties that were sold or distributed via land grants in 1834. The first non-Chumash people who settled in the area of modern-day Santa Maria were two Californios, descendants of Spanish settlers who petitioned to use the land under the Rancho Punta Laguna grant (1844). Under the Treaty of Guadalupe, when California was taken by the United States, the land grant would be honored even when it was no longer part of Mexico. Tensions during this transitional period illustrate the continued mistreatment of Indigenous communities by Spanish and mixed ancestry Mexican people. In 1824, Chumash at Santa Ines Mission rebelled. Mexico’s independence was supposed to mark a time in which Indigenous people would be treated as citizens. Chumash Peoples’ continued mistreatment by Mexican settlers and dehumanization under Spanish and Mexican governance for 54 years sparked a rebellion that spanned about three California missions. The rebellions concluded with the recapture of the missions in the same year, at which time the Chumash were pardoned and allowed to go back to live in them. While some continued life at the missions, others tried to survive a life where land was being taken by Mexican and U.S. expansion. Survival for Indigenous communities under Mexico meant working under highly exploitative ranchers during this time.

Between the time of Mexican independence and the grab of California, Oaxaca became a Mexican state (1824) after much resistance from authorities loyal to Spain. Many Indigenous people in the state formed part of, or were affected by, polarizing liberal and conservative movements. Moreover, the release of lands in Ñuu Savi from Dominican power did not mean that they would be given equally among Indigenous communities. The political storm of the time likely affected Ñuu Xnuviko and the rest of Ñuu Savi with the same economic decline that affected the rest of Oaxaca, weakening elites and spurring more movement within and outside ancestral boundaries in search of economic stability.

Post Mexican-American War 19th Century (1848 - 1900)

Interests in rich Californian soil and other opportunities for U.S. expansion led U.S. settlers to violate Mexican laws, and a war ensued in which California, along with other states that were part of Mexico, were ceded in 1848. While the California of today is mostly known to be progressive, many rural areas and centers in its urban areas remain marked with the dynamics of racism developed by Spanish-Mexican and English-U.S. settlers. Within the larger U.S.-Californian context, the Gold Rush (1848), the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865), and the completion of the first transcontinental railroad (1869) influenced growth and diversity in the area. Santa Maria was solidified in 1885, having grown in population due to the above influences. Oil exploration began in the Santa Maria area in 1888, while the agricultural industry expanded, attracting more economic interests.

Chumash that had once been a part of the Santa Ynez mission were given land in 1855 that would later become the only recognized reservation of Chumash in the United States. Their population, culture, language, and territory were greatly reduced by the end of the 19th century as California continued to grow. Other Chumash groups remained landless, looking for strategies to continue their lifeways or adapt to others, since Mexico had secularized its relationship to the Catholic church.

For Na Ñuu Savi, the second half of the 19th century was marked with political turmoil as different political groups tried to establish dominance. The turmoil continued into early 20th century Mexico under the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz (1876-1909), whose liberal reforms welcomed foreign nations and goods into Oaxaca, thus opening Indigenous Oaxacan lands and economies to international influence and extraction. By the end of the 1800s, the tribute system appropriated by the Spanish collapsed due to extensive land erosion and the privatization of land by Mexican and foreign entities, which furthered the migration of Na Ñuu Savi. The people of Ñuu Xnuviko were able to depend on themselves using artisan work adopted from the Spanish into the 20th century as the municipal area grew in population. This self-sufficiency came to an end in the 20th century as dependency on outside goods and customs grew since Na Ñuu Savi first entered the world economy through the boom of the Spanish cattle industry in the 16th century.

20th century (1900 - 2000)

The 1900s were filled with rapid changes for Na Ñuu Savi due to Porfirio Diaz’s politics. Ñuu Savi became a place that would import manufactured goods while exporting labor. Where people traditionally created their own wares, the allure and productivity of industry would push them to switch from handcrafted clothes, soap, and shoes, to commercially made products. The increase in prices for these goods and other items used in traditional occasions like patron saint festivals and weddings began to take hold in the first decade. The cattle that poor families depended on to sell during economic crises could no longer sustain them. The 1920s marked the first occasion where Na Ñuu Savi from Mixtepec left for the sugar cane region in Veracruz, walking about seven days to work in the industry there. In the 1930s, the greatest changes took place. Mexican agrarian laws failed to promote equality despite Indigenous communal lands becoming ejidos through which Indigenous communities could obtain land to plant on. The discovery of antimony in Ñuu Xnuviko in 1933 launched the construction of a dirt highway, through which a mining company majority-owned by entities in the United States would extract this resource from the area.

In this same decade, public education arrived in the municipality. The education system would serve to acculturate the townspeople into the ideals of the Mexican nation. Labor in the mines attracted people from outside Ñuu Savi, Na Ñuu Savi refugees who had been chased out of their eroded lands, and migrants who had left to find work in other parts of Mexico. U.S. and Mexican non-Na Ñuu Savi presence in this area would mark further instances of abuse and discrimination from Euro-American and Mestizo anti-Indigenous elites. Faced with the choice of the harsh work environment in the mines or the harsh agricultural work and journey that would define migration for Na Ñuu Savi, some chose to journey north with the introduction of the Bracero program in 1942. During this time, Na Ñuu Savi would begin to settle in places like Santa Maria, CA on Chumash land. Work seemed plentiful until the mine closed down in 1963 and the Bracero program closed in 1964. The United States had invested in the community of Tecojotes in Ñuu Xnuviko where the mine was located, and when they left, they took their investments with them, leaving the mines and the community empty.

Despite the end of the Bracero program, migrants continued to migrate to the United States without legal protections. My parents were born in late 1960 and early 1970; my grandparents had faced their younger years attempting to survive via migration and labor in the mine. My grandparents likely suffered under the duress of agricultural programs that began in 1975, which sought to support rural landowners through agricultural loans that were used to purchase foreign goods meant to aid the productivity of agriculture for competition with large agricultural industries. These loans and goods eventually led to large debts and the abandonment of traditional agricultural methods that furthered the erosion of lands. My parents, like many people in the town, achieved an elementary school education and a small degree of Spanish vocabulary. Papa was raised in migration, journeying to Chiapas and Veracruz with my grandfather. When Mama and Papa were married in 1993, a Spanish-Mestizo oligarchy was well established in many head towns across Ñuu Savi where migration to the United States was also well established. Mama and Papa spoke very little Spanish and no English, so the community of relatives that settled in Santa Maria and different towns across the United States became a resource for their survival. Different iterations of the farmworker programs in the U.S. and the disruption of the agricultural economy at the expense of Indigenous communities in Mexico through NAFTA continued the cycle of migration in the 21st century.

The 1900s marked seedlings of change for Chumash. The land that was given to them in 1855 became the only formally established reservation in 1901. Despite the death of the last Barbareno Chumash speaker in 1965, Chumash began to revitalize their cultural lifeways and ties in the 1970s as the reservation expanded in resources, land, and services. In 1976, the first recreation of a tomol, a boat traditional to the Chumash, was built and sailed. All Chumash by this time had different degrees of mixed Chumash ancestry that they were able to trace through mission records. When my parents arrived in 1993, they arrived largely disconnected from the history of colonization that had taken place on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border, not knowing that in their new home, the original people of the land had experienced similar changes as our ancestors because they had also been displaced from their homes and history. In writing this, I recognize the privilege that enables me to connect to both histories and the interpersonal work necessary to fill in the gaps related to them.

21st century (2000 - 2023)

The disconnect I touch on in the last section and the connections I’ve managed to make are the product of my modernization as a Na Ñuu Savi. My parents do not have the same linguistic and literary abilities as I do as a trilingual and literate person because the governments imposed on their home were not engaged in Indigenous interests. In their new home, I was tasked with aiding in interpretation at different institutions we would attempt to access. Ignorance of our needs and histories across both countries is reflected in the recent pandemic that began in 2020. While California championed access to Indigenous reservations and Indigenous migrant communities, gaps in addressing misinformation and insecurities in these communities were highlighted as the result of the anti-Indigenous chain of events that had occurred since the European invasion of Chumash territories and Ñuu Savi. The vast network of Indigenous migrant organizations already established across the state were instrumental in connecting information and aid to the Indigenous migrant population. Moreover, Indigenous communities were seen as a priority due to the historical neglect they have faced and continue to face.

The exploitation of Indigenous communities and lands continues to this day. The packed living conditions of Na Ñuu Savi so they can survive working in the agricultural industry and the lack of trust in systems that had failed them consistently would become a driver for deaths and sustained poverty not just due to COVID-19, but multiple processes before. Despite the constant movement and turmoil faced by Na Ñuu Savi, their communities and cultures remain strong, but they still wane in the face of modernity. Today, Chumash hold pow ows in their reservation in Santa Ynez. They have a casino from which they are able to accumulate wealth, and they continue to expand on their connections and resources for the sustenance of generations to come. Similarly, Na Ñuu Savi have amassed such a strong presence in Santa Maria that they hold their patron saint festivals in the area, bringing together families from both sides of the border to share language, culture, food, and to strengthen the bond between the homeland and their new homes. The present gives us a glimpse of a hopeful future in spite of a past that holds us back.

— Claudio Hernandez (Na Ñuu Savi/Mixtec) is a 2022–2023 Cultural Survival Writer in Residence. He is working on other writings reflecting on the shared history between Na Ñuu Savi (People of the Region of the Rain) and Chumash.

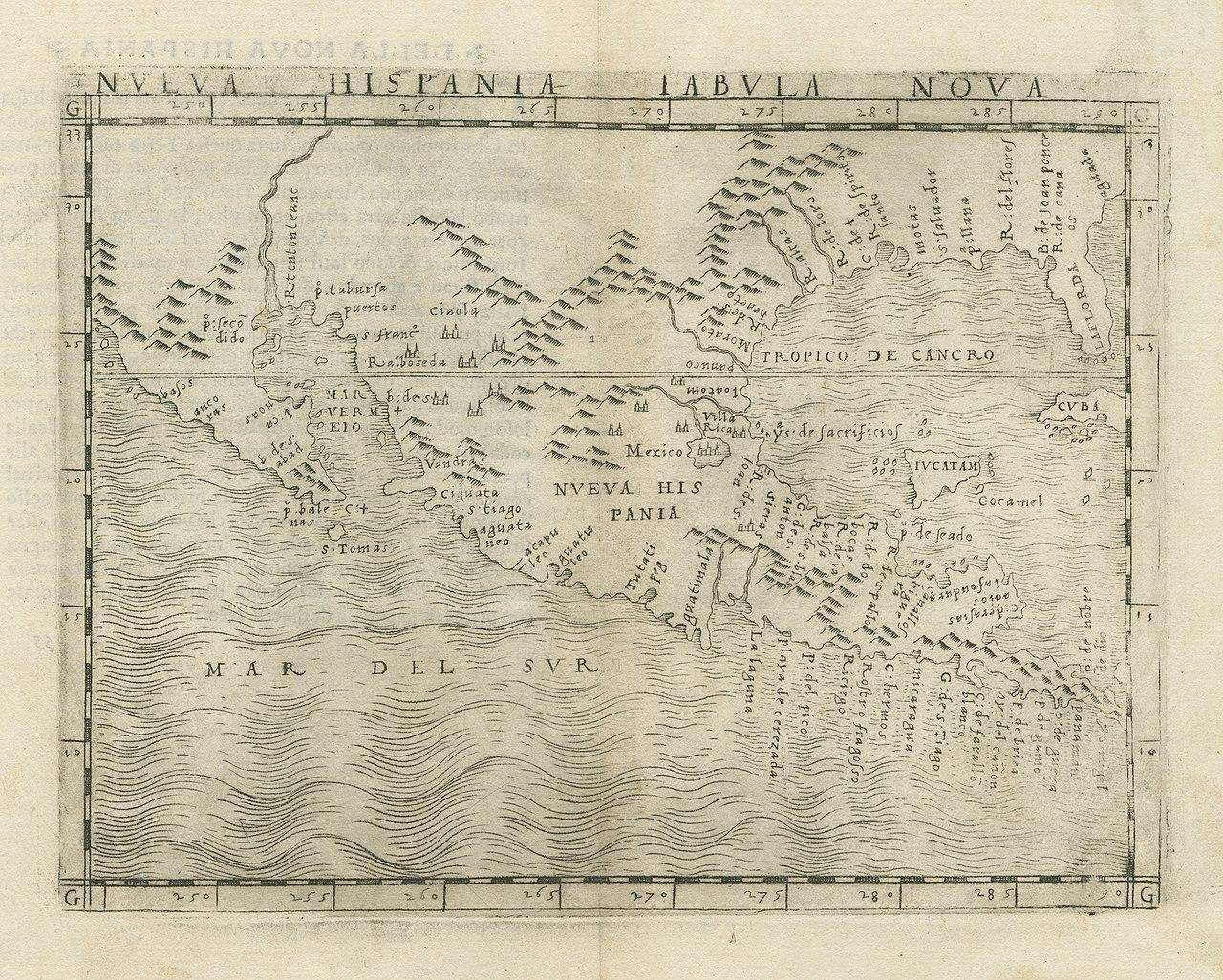

Top map: Giacomo Gastaldi's 1548 map of New Spain, Nueva Hispania Tabula Nova.