By Edson Krenak (Krenak, CS Staff)

April was a momentous month for the Krenak Peoples, as it brought both significant recognition in literature and a long-overdue formal acknowledgment of past wrongs. Indigenous Peoples received a formal apology for the human rights abuses endured during the military dictatorship era of Brazil (1964-1985) from the president of an amnesty commission investigating the crimes. A few days following this acknowledgment, one of our esteemed leaders, the renowned writer and environmentalist Ailton Krenak (Krenak), whom I have the privilege of working with, was inducted into the prestigious Brazilian Academy of Letters. This institution is celebrated for its exclusive intellectual fellowship, comprising some of the nation’s foremost literary figures.

During the ceremony on April 16, 2024, Ailton Krenak said, "I am here not to enhance the Portuguese language, but to bring more languages because we are not one, but 305 Indigenous Peoples in this country… My relatives have come from different parts of Brazil to be here. I can't mention every ethnicity here, there are many...I am here. I am Guarani, I am Kayapo, I am Xavante, I am them all."

In the other ceremonious event earlier on April 3, 2024, held at a Justice Statehouse with a stage featuring Brazilian States' flags and in a room packed with Indigenous people, jurists stood before Indigenous leader Djanira Krenak and said, "In the name of the Brazilian State, I want to ask forgiveness for all the suffering your people have gone through." The jurist is the president of the Amnesty Commission attached to the Human Rights Ministry responsible for investigating the dictatorship's crimes.

These offenses involved displacing the Krenak from their territory in southeastern Minas Gerais to construct what was referred to as a reformatory site. At this location, Indigenous people were subjected to torture, physical abuse, and were prohibited from speaking their native languages. Additionally, the military established a rural guard consisting of Indigenous individuals who were instructed in methods of torture. The commission also issued an apology to the Guarani Kaiowá Indigenous people, who were expelled from their lands in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul to accommodate agricultural ventures operated by non-Indigenous Brazilians.

Currently, our needs extend beyond simple recognition and apologies. Our communities continue to face severe issues, including lack of security, inadequate access to water, and poor nutrition. Many of our relatives are still caught in the prolonged process of land demarcation. This waiting period is fraught with challenges as we endure violence, poverty, and societal invisibility.

Flowery language and empty promises are as fleeting as chaff blown away by the wind. We urgently require tangible actions and the full enforcement of our rights, as enshrined in Brazil's 1988 Constitution and within international frameworks. It is time for concrete measures that truly honor and fulfill the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

To commemorate Indigenous Month in Brazil, Cultural Survival is sharing two significant articles. The first (below) is a letter marking the 60th anniversary of Brazil's military regime, in which we assert that mere apologies are insufficient. The second article is an interview with an Indigenous educator who is actively fighting for the sacred territories of land and knowledge in Rio de Janeiro's sole Indigenous village, Aldeia Maracanã. This community is engaged in a persistent struggle for official recognition as Indigenous territory, along with the protection and acknowledgment of their rights to land, education, and culture.

Letter to Brazilian Society: Don't Forget the Indigenous People of 1964-1985

On the 60th anniversary of the US-supported coup, Indigenous Peoples urge Brazilian Society not to forget and do justice

1978 Journal Palavra do Indio - “Indian Words”. Source Doc Virtual

2024 marks sixty years since the beginning of the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985). The details and amount of information that school or non-school history books narrate this period are indisputable, but we cannot ignore that many Brazilians still have vivid memories of this time of military authoritarianism. Among them, we are the Indigenous Peoples. In this letter, I want to ask you two things, but first, let me talk about something.

Although the dictatorship was an undemocratic and violent period, it intrigues me that there is a portion of the population that, motivated by recent political events, seems to yearn for the return of the military regime. However, I want us to shift our attention to an aspect of this time that often goes unnoticed: the experience of Indigenous Peoples. In this letter, which I hope will be a careful and reflective reading, I do not propose a detailed report or a history lesson, no; but to emphasize some notable events and present a concise request.

Since the arrival of the Portuguese in the lands we now call Brazil, Indigenous Peoples have been subjugated to an incessant cycle of violence, expropriation of lands and rights, genocide, and cultural destruction. The Brazilian State, shaped by colonial legacies, continued to perpetrate these crimes and atrocities against the first inhabitants and protectors of our forests, rivers, and biodiversity that adorn our nation.

The relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the State and, by extension, with Brazilian society is steeped in trauma. The State not only maintains violence but also fails to protect these communities, often being the perpetrators of violations. These traumas, although sporadically recognized in the national consciousness, still cause suffering to Indigenous Peoples.

The military dictatorship, now sixty years after its inception, brought an unprecedented level of violence and indifference to our indigenous relatives. What is alarming is the excess of knowledge about the dictatorship - an abundance of books, articles, and journalistic coverage, especially in recent years, under the administration of Jair Bolsonaro, history has once again become a commonplace topic. However, the Indigenous issue is once again made invisible and silenced, even in the face of the same rights violations.

The history of the Pataxó Peoples in Bahia repeats itself in a tragic cycle, like a Greek tragedy, in which the State and vulnerable communities are protagonists (We understand Antigona's pain!). This national amnesia, this collective refusal to confront and remember the violence suffered by Indigenous Peoples, is a serious failure. The 1984 document details the chronology of state violence to which these people were subjected - and, surprisingly, still face - in a reality that seems to echo the refrain of a film: "die, fall, and repeat." The lack of action to prevent the recurrence of these terrible events reveals a lot about the character and dreams of the country you intend to build.

The history of my Peoples was profoundly affected by the infamous Krenak Reformatory, a prison for Indigenous Peoples. It was the fate of those who, courageously resisting, refused to give in to the demands of a society marked by violence and injustice. They were confined and abandoned there, facing brutal conditions that surpassed the already severe hardships imposed by prisons under dictatorial regimes around the world. Many were forced to flee, hide, and protect themselves, often at the cost of their own cultural identity. This is a sad parallel that extends to other Indigenous Peoples across the Americas, from Canada to Uruguay. Latin America, stained by the blood and tyranny of the dictatorial governments of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, still suffers from a legacy of suffering, an open wound that still needs healing.

Dear Brazilian contemporaries, worse than minimizing or trivializing this memory is forgetting and ignoring these traumas of Indigenous Peoples. I am referring here to what has been forgotten and what many ignore. During the military dictatorship, the situation of Indigenous Peoples was notoriously reported – both in the country's main newspapers and on the international scene –, describing scenes of violence, hunger, disease, neglect, and countless deaths. The National Truth Commission and other researchers studied the impact of this time on 10 of the more than 300 Brazilian Indigenous communities, finding more than 8,350 violent deaths.

With the promulgation of Institutional Act Number Five (AI-5), in December 1968, the findings that emerged from the Figueiredo Report (a document produced by the Dictatorship itself) were suppressed from public discourse, and justice was abandoned. Many of those dismissed resumed their positions at FUNAI. No arrests were made. Farmers who occupied Pataxó lands, for example, continue to commit violence and murders as they increase their possessions, as you can see in "The Killing of Pataxó Spiritual Leader and Activist Exposes Violence of the Law Against Indigenous Peoples in Bahia, Brazil."

LAW Bulletin - Year I No. 1 June 1983 - Legal Department of the Pro Indian Commission of São Paulo

(For the English version: 1957 – A new wave of violence against the Pataxó Indians in Bahia: "More Indians are expelled; farmers reclaim the land."

1957/75 – SPI after FUNAI: The Indigenous Posts "return" to the state of Bahia; indigenous lands are taken by farmers.

1976/78 – Indigenous Posts are deactivated by the Bahia government; indigenous lands are again leased to farmers (by the government).

This section of the document outlines a period of continued aggression and dispossession suffered by the Pataxó people, emphasizing the exploitation of their land and the undermining of their rights.)

The crimes listed in the report were vast and serious: murders, forced prostitution, torture, slave labor, and diversion of Indigenous resources, among others. It is shocking to consider that the origins of the fortunes of many prominent families can be tied to such atrocities. Look at the history of the richest families in the Northeast, the Center-West, Bahia… you will see what I am saying.

The violence was so extensive that the State's official documentation does not allow the financial damage inflicted on the indigenous people to be accurately assessed in order to claim fair compensation. Official documents were tampered with, accountability processes were rigged, and evidence was destroyed. However, we have not forgotten.

The Cinta-Larga, alongside other groups in central-western Brazil, suffered brutal attacks: aerial bombings, poisonings, shooting executions, and machete cuts. These genocidal acts are documented in the 11th Parallel Massacre in Mato Grosso, which occurred in 1963, as it became known.

How many Indigenous leaders, shamans, and defenders of Original Peoples lost their lives in the fight for justice? History records some names - I encourage you to seek out and honor the memory of these individuals! However, finding this information can be a challenge, as the streets and squares you walk through often honor colonels, generals, and colonial figures rather than recognizing the victims. May we move towards a society that values and celebrates the true heritage and the heroes who fought to preserve human dignity and rights, the life of the planet, and Mother Earth!

An Indigenous person on a "pau-de-arara" is displayed to authorities in Belo Horizonte, Brazil in 1974 — Photo: Jesco von Puttkamer/Reproduction Globos news/Der Spiegel (During the establishment of detention centers for Indigenous populations, the military subjected incarcerated Indigenous persons to public humiliation in town squares and throughout military parades).

On this 60th anniversary of the US-supported coup, Indigenous Peoples urge both you (and the United States!) to release classified documents to make justice! As Kornbluh stated to Responsible Statecraft, “The degree to which the United States is sitting on documentation about repression in Brazil is the degree to which the United States is not assisting Brazilian society in reminding itself about the horrors of what happened behind closed doors in secret detention centers.”

Still, in the chapter Violations of Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the Truth Commission Report, these frightening numbers of deaths are presented in a country that was promoted abroad as a country of kindness and courtesy (don't forget: these ten Indigenous Peoples are just a sample of the that has been documented):

Cinta-larga people (State of Mato Grosso), 3,500 dead

Waimiri-Atroari people (State of Amazonas) - 2,650 dead

Tapayuna (MT) - 1,180 dead

Yanomami (AM/RR) - 354 dead

Xetá (PR) - 192 dead

Panará (MT) - 176 dead

Parakanã (PA) - 118 dead

Xavante Marãiwatsédé (MT) - 85 dead

Araweté (PA) - 72 dead

Arara (PA) – 14 dead.

The National Truth Commission has chronicled grievous human rights offenses against ten Indigenous ethnicities, detailing the appalling number of fatalities in massacres, the usurpation and forced displacement from ancestral lands, the rampant spread of infectious diseases, and the rampant occurrences of arrests, torture, and abuse. This legacy of anguish continues to cast a shadow over our collective conscience. Healing from such trauma is an ongoing process, one that will only be realized when communities such as the Yanomami, Pataxós, Guarani, Mura, and Kaingang witness the formal recognition and demarcation of their territories, receive appropriate restitution, and can finally enjoy the tranquility of living in peace.

This letter makes a simple request: Remember what happened to Indigenous Peoples and work hard not to repeat past mistakes.

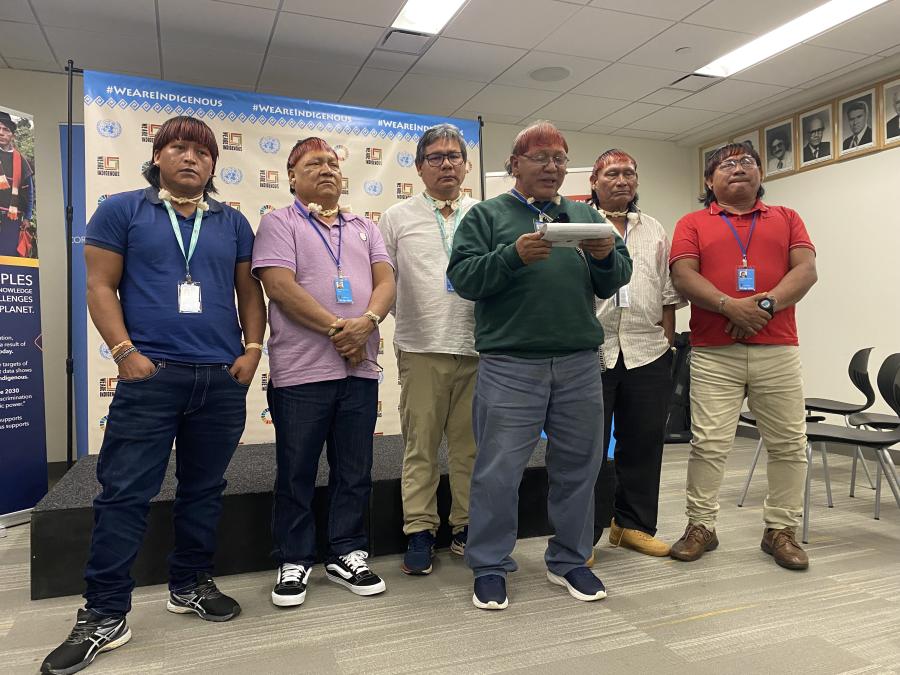

Top photo by: Pedro Biondi.

Você pode ler a versão em português aqui.